Editor's note: We recognize how quickly Charlotte has changed over the years, so here's us trying to preserve its story. In this series, native author David Aaron Moore answers reader-submitted questions about historic places in Charlotte. Submit inquires about unusual, noteworthy or historic people, places and things to davidaaronmoore@post.com.

In Charlotte's Coulwood neighborhood, a recently completed highway connects Highway 16 (Brookshire Freeway) to Freedom Drive. It's called Fred D. Alexander Boulevard. Can you tell me something about the man the road is named after? - Margaret Stewart, Paw Creek, North Carolina

- David Aaron Moore

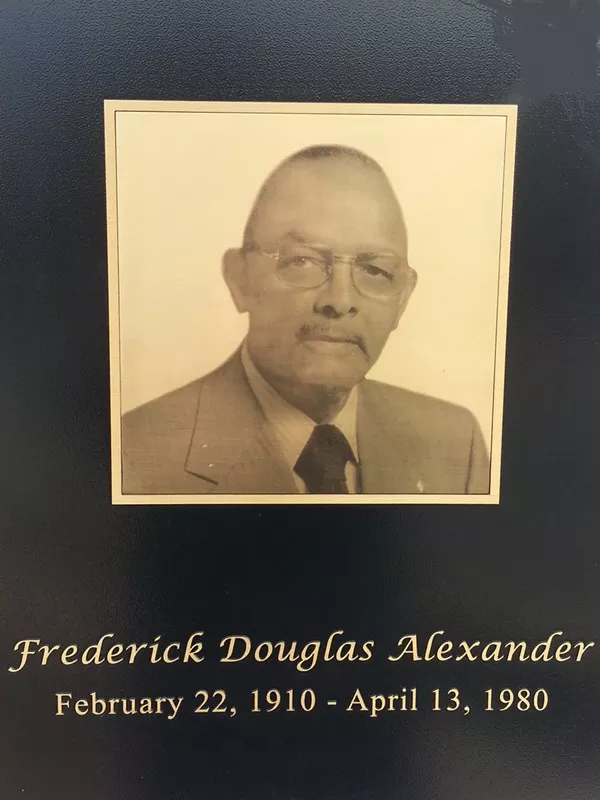

- Metal-plate photographs are attached to several of the columns on the main bridge of Fred D. Alexander Highway

If anyone deserves a highway named after him, it's Frederick Douglas Alexander. He's an important figure in Charlotte's 20th century for a number of reasons. In 1965, he was tapped as the city's first African American City Council member. By 1971, he led council as mayor pro tem. His political career took a big leap forward when he became a state senator, a position he held from 1974 to 1980.

But let's backtrack a bit. Alexander didn't pop up on the Charlotte political landscape overnight. His was a journey that began in 1910 with his birth, but an incident in the 1960s thrust him into the national spotlight.

During a particularly ugly period of racial unrest in Charlotte's history, unidentified hate groups targeted four key figures in the Queen City's civil rights movement. Among them were Alexander; his brother, state NAACP President Kelly M. Alexander; attorney Julius Chambers; and Dr. Reginald A. Hawkins.

On the morning of Nov. 23, 1965, between 2:15 a.m. and 2:30 a.m., dynamite exploded near the homes of the four men, all on the west side of town. The homes of the Alexander brothers, which were located next to one another, sustained the most damage. Interior and exterior damage was considerable.

"It was a well-organized group," said then-police chief John Hord to the local media. "I guarantee you it was people who knew what they were doing. Whoever it was, they knew the explosives, they knew the sections and they knew how to get in and get out quickly."

Said Councilman Alexander of the individuals responsible for the explosions: "They were experts. They did a complete demolition job."

The malicious violence was horrifying for most Charlotte residents and was viewed as a blight on the state's civility. Citizens rallied around the victims. Mayor Stan Brookshire organized a relief fund and raised money to repair the houses. The culprits were never found.

That was the incident that made Frederick D. Alexander a nationally known figure in American history. It isn't the reason he had a road named after him.

Alexander's father was a prominent figure in the city; he founded the Alexander Funeral Home, which is still in operation. His father's relevance opened a doorway for Fred, who left Charlotte for a time to attend Lincoln University, in Chester County, Pennsylvania. It was there that he was asked to go to Africa by a classmate, to help gain freedom and equality for many of the native people who were then dominated by foreign governments. "My God," Alexander told journalist Harry Golden. "I came from Africa ... if I can go there to help his people, I can go back home and free my own Africa."

After college, Alexander did just that. He returned to Charlotte and dedicated the rest of his life to achieving equality for African Americans and oppressed people of all races in his hometown. He worked hard to register countless black voters and to help organize campaigns for supportive candidates.

By the 1960s, Alexander, and many others around him, realized he possessed the qualities to run for office. After immersing himself in local government for many years on a volunteer basis, he had captured the support and friendship of many Charlotteans of all ethnicities. It was through their support that he was elected and would go on to serve nine years on council, followed by six in the state senate. He died while still in office, on April 13, 1980. He is buried in York Park Cemetery in Charlotte.

Of the many achievements Alexander is recognized for, the one he was the most proud of was the removal of the fence that once divided Elmwood and Pinewood cemeteries in downtown Charlotte. "It's cheaper to take it down than to maintain it," he said of the barrier that separated the racially segregated city cemetery. "Plus [there's] the insult that comes with it."

It was taken down on Jan. 7, 1969.

David Aaron Moore is the author of Charlotte: Murder, Mystery and Mayhem. His writings have appeared in numerous publications throughout the U.S. and Canada.