Editor's note: In this series, local author David Aaron Moore answers reader-submitted questions about unusual, noteworthy or historic people, places and things in Charlotte. Submit inquires to davidaaronmoore@post.com.

Is there one particular crime in Charlotte history that has not been solved - one that you think will likely never be solved? - Spencer Anderson, Charlotte

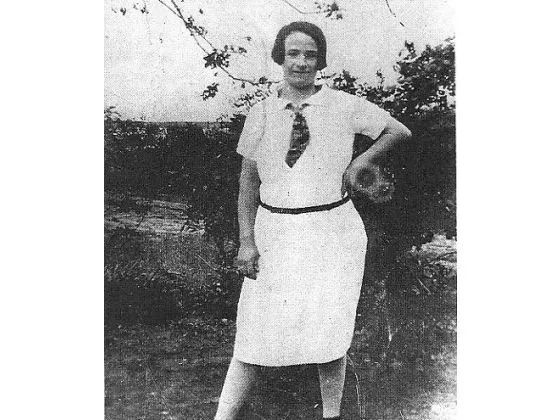

There are many, but the murder of Ella May Wiggins stands out to me. Technically it's a Charlotte Metro crime because it occurred in Gaston County, but it brought enough attention to the region that I think it merits mention here.

In the late 1920s, Wiggins was an activist and champion for equal pay for women and children. She worked hard to bring black and white mill workers together as one organized union force.

Originally from Seviersville, Tenn., she moved to Bessemer City in Gaston County and took up residence in the predominantly African-American neighborhood known as Stumptown.

Although she was only 26 when she moved to Bessemer City, she had already given birth to nine children. Four of them died from whooping cough and she was left to raise the other five by herself when her husband John abandoned the family.

Despite the period and that she was Caucasian, Wiggins was endeared by her African-American neighbors, who looked after her children while she worked 12-hour days, six days a week at the Gastonia American Textile Mill. Her take-home pay was roughly $9 a week. When she wasn't working, she was a volunteer bookkeeper for the mill workers' union, spoke at rallies and testified before Congress about labor practices in the South

From a 1920s perspective, Wiggins was tantamount to a modern-day activist.

Wiggins also wrote and performed workers' ballads, which served as rallying calls to underpaid and overworked mill employees. There were several, but perhaps the best known is "A Mill Mother's Lament," which Pete Seeger covered decades later.

Although Wiggins was widely respected in the labor movement of the day - and has become posthumously legendary - sentiment toward her was divided back then. Many saw her as a heroine, while others viewed her as a "race traitor" and Communist troublemaker, often referring to her as an "outsider" because she was not native to Gaston County.

On the evening of Sept. 14, 1929, she and a truck load of 21 other union members were en route to a committee meeting when they were stopped by an armed and misguided anti-communist mob, many of whom were also non-union sympathizers. She and the other union members initially escaped in the truck but were eventually stopped by a gang of armed men five miles away. During the confrontation, Wiggins was shot in the chest and killed. According to historical documents, her five remaining children were sent to live in orphanages.

Initially charged with manslaughter in Wiggins' death were seven men: F. T. Morris, Theodore Sims, Troy Jones, George Lingerfelt, Lowery Davis, I. M. Sossoman and Will Lunsford.

By the time the case came to trial, charges had been dropped against three of the original men and an additional arrest had since been made: local Deputy Horace Wheelus.

In a story carried by UPI dated Feb. 25, 1930, a witness named Julius Fowler pointed a finger at Wheelus: "I was looking him right in the face. Wheelus steadied the pistol by laying it across his left arm." Immediately after the shot was fired, Wiggins cried out she had been shot.

After testimony from 29 witnesses and only 30 minutes in deliberation, all defendants were found not guilty.

Moore is the author of Charlotte: Murder, Mystery and Mayhem. His writings have appeared in numerous publications throughout the U.S. and Canada.