Productions of August Wilson's Fences come around about as often as 17-year cicadas, which is about as often as actors come along who can do justice to Troy Maxson, its tragic hero. Maxson is baseball royalty, blessed with Babe Ruth-Josh Gibson slugging power and cursed with a snarling, bitter Ty Cobb temperament. He should have been the black ballplayer who broke the color line - so he feels - and become the liberating terror of the major leagues.

But he peaked years before Jackie Robinson began his pioneering exploits with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. So now in the '50s, when players like Mays, Campanella, and Aaron have demonstrated that the black ballplayer is here to stay, Maxson is collecting trash on the streets of Pittsburgh, burning to become the first black man to drive the truck. Quite a comedown from his one-time celebrity, and his wife and sons bear the brunt of his still-seething anger.

Wayne DeHart was a very fine Troy when Theatre Charlotte staged this show in 1996, giving the mean father and the faithless husband a wiry strength. Yet he was also a natural playing the drunken deteriorated athlete, his vaunts aimed at the specter of Death like those of a wily, grizzled coyote. Calvin Walton has a similar wiry strength in the current CPCC Theatre production directed by Corlis Hayes, particularly corrosive in his denials that times have changed. I'd say he was slightly less nasty to his family and a lot more defiant towards Death, whom he envisions as a mighty pitcher with a blinding inside fastball. It's a nicely gauged balance.

The tables are metaphorically turned in Troy's strained relationship with his son Cory. Each time the athletically gifted teen seriously crosses his dad, Troy calls a strike on Cory - as if he's pitching to his son. The count reaches "Strike Two" in Act 2 before the final catastrophes hit.

Branden Cook doesn't appear to have an abundance of acting polish as Cory - or the swagger of a high school football star - but his portrait of a son who has always walked on eggshells around his father is perfection. Even his grand moment of standing up to Troy, saying he's longer intimidated, has a convincing residue of trepidation. One last treat in Cook's performance occurs when he pulls out a harmonica from his Marine jacket and sings about that old dog "Blue," an heirloom from his hateful dad that has seeped into his soul.

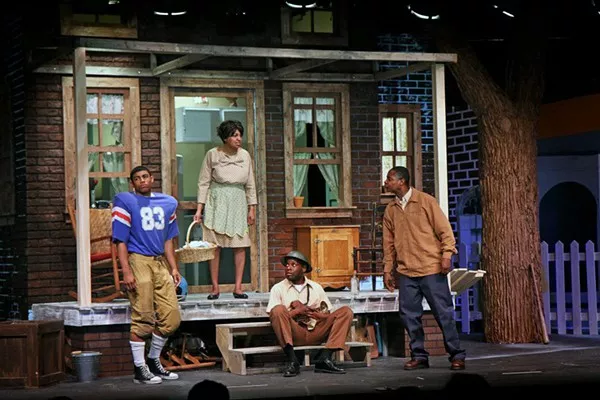

Rebecca Primm gives the production a cagey set design. The Maxson home is about as ramshackle as it can be, with its front steps close enough to us downstage for all the actors to remain audible. Yet the home is substantial enough, with a visible kitchen inside the front door and an old tree off to the side, to warrant the sturdy fence that Troy keeps nagging Cory about. James Duke's lighting design effectively partitions those key moments when Troy calls out Death or when his feeble-minded brother Gabriel calls on St. Peter, and Jeff Murdock's sound design offers a nice blues primer between scenes, with prime cuts of Odetta and Dinah Washington.

The cast has at least two more actors powerful enough to audition for the role of Troy. Troy's longtime friend, co-worker, and drinking buddy, Bono, is effectively nuanced in J.R. Jones's portrayal - his frank admiration for his pal wrapped around a firm backbone when the time comes to stand up to the former baseball star regarding his ongoing infidelity. No less subtle and effective is Jonavan Adams as Troy's eldest undervalued son, Lyons, cooler and better-adjusted than his dad while inheriting his musical inclinations, his self-assurance, and his sense of honor.

Lillie Ann Oden doesn't perform in Charlotte nearly as often as I'd wish, but Troy's wife Rose would no doubt rank among her most human roles even if she had been onstage every week for the last six years in a different show. During Act 2, she has monologues that bear comparison with any words Linda Loman ever spoke - clearly better as a wife and a woman by evening's end than Troy has deserved.

Last Sunday's matinee bore out the contention that this Fences cast is extra deep, for I sampled James Lee Walker III's understudy, Dominic Weaver, as the shrapnel-crazed Gabriel, and he was wonderful - dopey yet likable - from beginning to end. There was just a little something amiss at the very end, either because of Weaver's reading or Hayes's direction. It's a tricky ending because nobody speaks the affirmation embedded in Wilson's stage directions.

I'm hoping that the affirmation is there when Walker concludes and that he's not leaving the audience with the impression that Gabe has expired in an epileptic fit. There's ample tragedy in Fences without that at the end - paired with numerous other heartwarming consolations and conciliations.