Tennessee Williams never explicitly said that all characters in The Glass Menagerie must be white. Nor did the folks at Dramatists Play Service, responsible for licensing the 1945 play to Theatre Charlotte for their current production. But when Williams named one of his characters Jim O’Connor and told us that he’d sung the role of the Pirate King in The Pirates of Penzance, he was certainly hinting strongly enough.

So it would seem fairly obvious that director Tim Ross, in presiding over an all-black Menagerie is clearly violating the playwright’s intent. Yet to some extent, Williams is anticipating alterations of his text – otherwise, there must be an audible “fiddle in the wings” of every production as decreed by our narrator, Tom Wingfield, in his opening speech. Ross does more than discard that fiddle, transposing the action of the memory play a decade forward to the 50s, excising Tom’s references to Guernica and the Spanish Revolution, and discreetly changing the Gentleman Caller’s last name.

That’s hardly enough in the early going when Amanda Wingfield, Tom’s mother, prattles on about the 17 gentlemen callers who gathered at her feet back in the good old days down South in Blue Mountain – Amanda’s throwaway remark, “we had to send the nigger over to bring in folding chairs,” is presumably rehabilitated in all modern productions. One must also don historical and social blinders when Tom’s crippled sister Laura bolts out of secretarial school and nobody in this St. Louis tenement can think of any other occupation that the pitiful young woman could possibly take up.

We’re not really exploring actual Afro-American history here as much as trying to enter a colorblind parallel universe where a black Amanda could have nobly endured missing all her chances at bank VPs and the like who once vied for her hand. So it’s when Glass Menagerie breaks free of its wider social contexts, exploring the Wingfields’ family dynamics and Laura’s spiritual paralysis, that the racial transposition can fully flower.

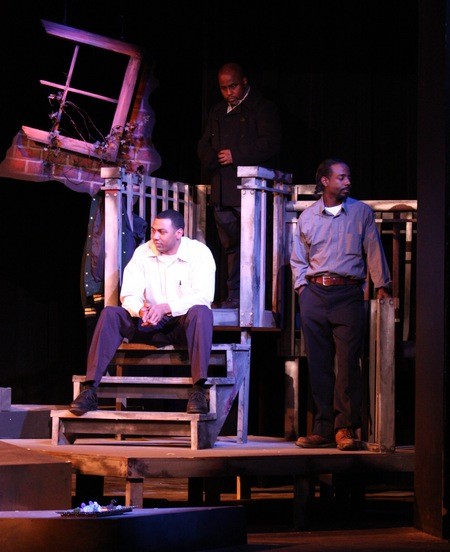

I don’t think there’s a single actor in Charlotte these days who can equal Sultan Omar El-Amin’s ability to project teen and young-adult resentment toward the elder generation – the best I’ve seen hereabouts since Hank West could credibly be cast in such roles. So there’s a core of fiery strength at the heart of Theatre Charlotte’s production, though Ross does split the role of Tom in two. That concept could have become ludicrous if an actor as strong as Ron McClelland hadn’t been found to do the elder Tom. There’s extra smoke onstage, particularly near the end when both smokers are onstage, but McClelland makes the “blow out your candles” speech more powerful than any I can remember.

For that to happen, we need a damn fine Laura, which we get in Ericka Ross, whose nerdiness is as spot-on as her limp. Nor does Jonavan Adams let us down as the Gentleman Caller, building his portrait of the lapsed high school hero with a beautiful mix of lingering vanity, meticulous courtesy, and slightly glib empathy, all enfolded in Williams’ gum-wrapper of vapid get-ahead clichés.

Nobody has a more difficult hill to climb than Corlis Hayes, who plays Amanda as if all her fond memories of her past glory are as verifiable as Gentleman Jim’s. Of course, it’s a conspiracy, with Ross and El-Amin buying into the bulk of her spiel. Their promptings don’t get us over that hump completely, but their credibility when we reach the crux of this drama is more than sufficiently triumphant.

Frankly, I was surprised that this Williams masterwork could survive such a frontal assault and yield such a powerful wallop. I recommend your giving it a try.