Erick Velazquillo wants the American dream. The 22-year-old has lived in the Charlotte area since age 2, when his parents brought him here illegally from Mexico. He graduated from South Mecklenburg High School and Central Piedmont Community College, and he'd like to continue his education so he can become a nutritionist. But Velazquillo is caught in a system that seems to block him at every turn, dangling his dream just out of reach. Currently he's facing deportation, although U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has closed his case "administratively." That doesn't mean much. Velazquillo is no closer to becoming an American citizen. ICE could renege on its decision at any second.

Velazquillo decided to step forward with his story, and he's become Charlotte's defacto face of the DREAM Act. The bipartisan federal legislation — which stands for Development, Relief and Education of Alien Minors — has been stuck in Congress since 2001.

If enacted into law, the DREAM Act would pave the way to citizenship for undocumented youth. To qualify and be granted conditional permanent residency, the immigrants would have to have entered the country before age 15, lived here for five years prior to the enactment of the bill, graduated from an American high school and either been accepted into the military or a college. In addition, they must demonstrate "good moral character" (i.e., they can't have a criminal record). After five and a half years, and attending college or serving honorably in the military (as thousands of undocumented immigrants do), they would then be able to apply for legal permanent residency, and later citizenship.

But that's the dream. The reality is that currently people like Velazquillo live in fear and embarrassment, wondering if today will be the day they'll be picked up and deported to a homeland they never really knew. It's not like the Velazquillo family hasn't tried to become documented citizens. "We've been trying for years to see if we could pay a fine or do something to change our status," said Angelica, 25, Erick's sister who is also undocumented. She said the family pays taxes, even though they don't and won't receive benefits, such as social security. Meanwhile, most people who know them didn't realize the family was undocumented until Erick was picked up by the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department. The family had kept their immigration status to themselves because they feared its pervasive negative stigma.

Erick Velazquillo faced the law for the first time last October when a police officer stopped him for driving on a dark road with his high beams on. Police then arrested him on charges of driving with an expired license and because of his immigration status. At 16, he had obtained a license legally, but when it came time to renew it, the laws had changed and he couldn't. That's all the officer needed to cart him to jail and report him to ICE, even though Velazquillo doesn't have a previous criminal history, and despite a directive from the head of ICE instructing local governments to help the federal government save money by using discretion in such cases. The idea is to not fill jails and courtrooms with people who aren't actual criminals, especially if they're students. Many local officials aren't following that directive. "I would say they're completely ignoring it," said Angelica Velazquillo.

The Velazquillos, like many undocumented youth, only know America as home. It's not their fault that they're undocumented, though neither Erick nor Angelica are ashamed of their parents for seeking a better life for the family. But because of their parents' decision, Erick is facing deportation to a country where his only relatives are elderly grandparents he barely knows, where he doesn't fully understand how the system works and where he only has a rudimentary understanding of the language.

Velazquillo isn't alone. According to the Pew Hispanic Center's 2009 American Community Survey, released earlier this year, 37.4 percent of American Latinos were born in foreign countries, and 23.7 percent of them graduated from high school here. Now they're stuck in a system that makes it difficult for them to become citizens, which, in turn, makes it difficult for them to work or go to school. (Many colleges make attending school unaffordable — insisting undocumented students pay out-of-state tuition rates, even though they may have resided in that state for most of their lives. Even if the students pay the hiked rates, schools often force them to the end of the line during registration and have been known to pull scholarship offers.)

Once these young people turn 18, said Domenic Powell of the N.C. Dream Team, their presence in the U.S. becomes officially unlawful. "It's a sticking point for undocumented youth," he said, because that alone can "make it impossible for them to correct their status."

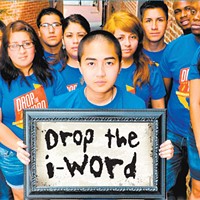

Part of a larger national movement, the N.C. Dream Team is a group of documented and undocumented youths who have banded together not only to support the DREAM Act but also encourage undocumented immigrants to step out of the shadows — a dangerous act reminiscent of the civil disobedience of the Civil Rights years. (The Dream Team is planning a coming-out day in Charlotte on Sept. 6.) Increasingly, undocumented immigrants are willing to take that risk because they want people to know they're not criminals; they want to study, earn their documentation and become contributing members of American society.

The N.C. Dream Team formed last year when three undocumented immigrants went on a several-day hunger strike outside of Sen. Kay Hagan's Raleigh office in an effort to convince her to support the DREAM Act. She voted against the act, although she now claims to support it. In December 2010, a UCLA North American Integration and Development Center study indicated the estimated 825,000 to 1.2 million potential beneficiaries of the DREAM Act could "contribute trillions to the U.S. economy" over a 40-year period. While the act doesn't have the backing of N.C.'s senators — Richard Burr also voted no when it was reintroduced in May of this year — President Barack Obama has voiced his support ... sorta.

After swearing he understands the students' concerns, the president has said he will not use his executive powers to override Congress. "Now, I know some people want me to bypass Congress and change the laws on my own," he said during a July address to the National Council of La Raza, the country's largest Latino civil rights and advocacy organization. In response, another group of young adults — six of them members of the Charlotte Latin American Coalition's United 4 the Dream youth group, which had traveled to Washington to challenge the president — stood with their arms crossed above their heads. Wearing red shirts emblazoned with "OBAMA: STOP DEPORTING DREAMERS," they chanted, "Yes, you can!"

Those young protestors, said Jess George, director of the local Latin American Coalition, "are on the cutting edge of courage. They have so much to lose, which makes their action so much more profound."

Erick Velazquillo's sister Angelica puts it this way: "We've come to realize that if you're silent, nothing is going to change."