No matter where New York singer Ismael Miranda performs, the veteran Fania Records sonero, known affectionately as "El Niño Bonito de la Salsa" (the Pretty Face of Salsa), always pulls out the popular standard "En Mi Viejo San Juan." Like so many Puerto Ricans of a certain age, Miranda, who is 67, was born on the island but raised on Manhattan's Lower East Side. "En Mi Viejo San Juan" tells the tale of an aging Puerto Rican living abroad, knowing he will likely never again see his beloved Caribbean birthplace.

"Time passed and destiny mocked my terrible nostalgia," goes one line of the iconic song, as translated in English. "And I couldn't return to the San Juan that I loved . . . My hair whitened, my life fades away, and death calls for me. . ."

Charlotte singer Joseph Samuel Quisol, 23, had never stepped foot on Puerto Rican soil when he sat down three years ago to rewrite the words of this classic bolero that's become P.R.'s unofficial national anthem.

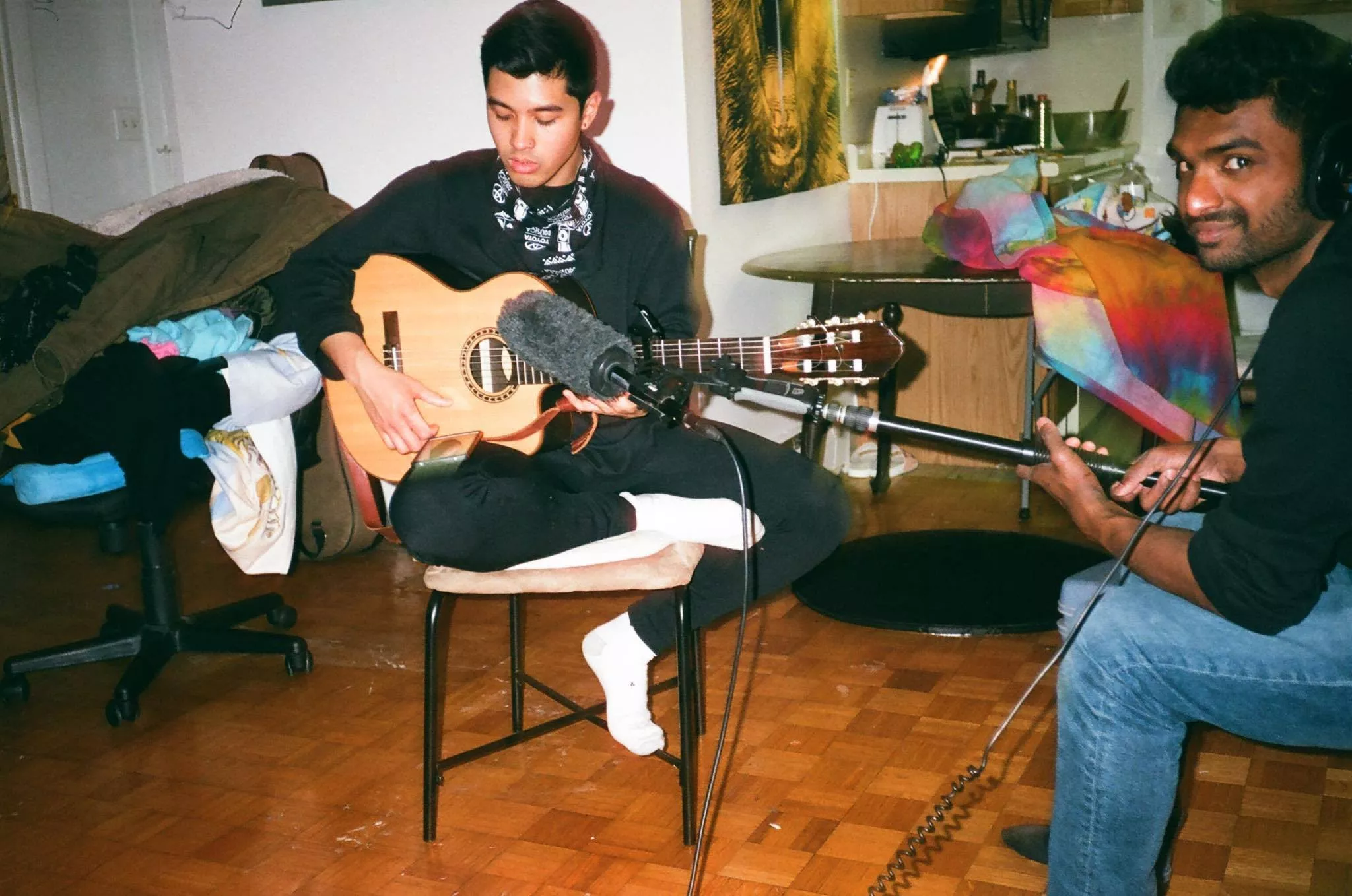

- Quisol strums an acoustic guitar at Hermit Mo Studios in December. (Photo by Mo Kwok)

"I kept the melody but translated some of the lyrics into English and made it from my perspective," says Quisol, who was born of Puerto Rican and Filipino heritage in Sacramento, California, and raised in the Queen City.

"En Mi Viejo San Juan" was a favorite of Quisol's abuela — his grandmother — who deeply identified with the words. "She had told me about the song, and she hasn't been back there in forever," Quisol says. "But that was not my experience with Puerto Rico. For me, it was this place that I had never been to, but that I had seen in family photos.

"So I adjusted the lyrics to talk about learning Spanish in the United States and hearing about this mythic land across the ocean where everyone's from; it is our place, but it was a place I'd never been to."

Quisol wrote the new lyrics as a way to engage with other second-generation Latinx immigrants. "I think a lot of people of my generation can identify with being from immigrant families and hearing these legends about these faraway places that are home to our parents and our grandparents," he says, "but having no real connection to the physical places ourselves."

"En Mi Viejo San Juan" took on profound new meaning in the wake of Hurricane Maria's devastation this past September, and Quisol decided to include a raw, acoustic rendering of his version as a stand-alone bonus track with The World Keeps Turning, the debut EP from his band, also called Quisol, which comes out February 2 on his Bandcamp page. The proceeds from the stand-alone track will go to help the people of Puerto Rico, who have been largely forgotten in our 24/7 news cycle, but who are still desperately struggling and in need of relief.

The World Keeps Turning is brief — a mere three-song introduction to a sound Quisol calls "Latinx Future." There's the ringing guitar tones of the indie-rock song "One More Kiss," the full-on Latin-jazz flourishes in "Everything and One Thing" (for which he will release a video on the day of the album release), and the bossa nova shuffle of the title track, in which Quisol sings of the ever-turning wheels of change, both personally and culturally.

He wrote the songs between 2014 and 2016, while studying political science at the College of Charleston in South Carolina. "In Charleson I never found a band or people to play with, so I was writing a lot on my own, just on guitar, and producing stuff in my bedroom," he says.

When he returned to Charlotte in 2016, Quisol put together his band with a mix of old friends he'd played with in high school and new ones, most of whom are of various Latinx heritages.

"I would come back on breaks during college and hang out with Nik [Maldonado, who plays percussion] and Kevin [Washburn, who plays saxophone]," Quisol remembers. "They've played with me forever, and we were friends and we started looking around and saying, 'Look, we're all different kinds of Latinx' — Nik is Puerto Rican, Kevin's Paraguayan, Sharad [Wertheimer, a co-songwriter] has Guatemalan roots. So we just kind of wanted to claim stuff that came from that. And then we met Michael [Gonzalez], who plays congas with us. He and I started dating, and although that relationship ended, he added a lot to the music and was on the same wavelength as us — learning congas, loving salsa, and wanting to do new music that incorporated some of that."

- Quisol (from left) with band members Michael David Gonzalez, Randall Davis and Nikolas Maldonado. (Photo by Lex Paige)

After recording the EP and playing numerous live gigs around Charlotte, both solo and with his band, Quisol set off to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he is currently working on his master's degree in Art in Education at Harvard University. His program combines music, education and arts fundraising. When he returns to Charlotte after graduating in May, Quisol plans to bring what he's learned back home and put it to work in public spaces that promote the intersection of art, music and community activism.

He points to Charlotte spaces like Area 15 and Camp North End — "places where people do art, where people have offices, where people come together to do organizing," Quisol says. "For example, when the Charlotte Uprising was going on, a lot of meetings and training happened at Area 15. So I want to eventually facilitate spaces like that, and to create new spaces.

"I see myself as kind of a bridge between different groups of people who come together to do things," he says.

For Quisol — a young, queer, Latinx musician, community organizer and political activist — the bridge he seeks to become is a broad one, and Harvard has the resources for him to lay a strong foundation for it. When I catch up with him by phone on a recent weekday afternoon, he is walking across Harvard's storied campus, attempting to speak to me through the crackle of a powerful wind.

He approaches the sprawling Harvard Science Center, with its Leggo-like tiers that descend, staircase-like, to the ground. "Compared to the rest of the campus, which is historic and brick, there's a lot of glass and steel beams," he says of the building, which was designed by the Catalan architect Josep Lluís Sert. The Science Center stands in stark contrast to Harvard's more historic structures, such as Holden Chapel, which dates back to the 18th century.

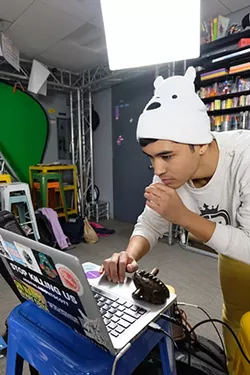

- Quisol performs a live looping and DJ project at Harvard’s Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning. (Photo by Carolyn Ho)

"Right now, there's a lot of people in here," Quisol says. "I'm in a café inside the Science Center, about to sit down. A lot of undergraduates are around me, studying."

Quisol has been studying, too, taking classes like 'Managing Financial Resources in Non-Profit Organizations," and studying music under some notable professors — the improvisational jazz pianist Vijay Iyer and the Grammy-winning jazz bassist and singer-songwriter Esperanza Spalding. Under Iyer, Quisol worked with a South Indian classical percussionist who helped him expand his rhythmic vocabulary.

"We would put together ensembles every month — like three to six people — where we would write music and then perform it at a concert at the end of each month," Quisol says. "I worked a lot with loops in the class, which is something I had done in my live performances in Charlotte. And we had a great saxophonist, Jonah Philion, who used my loop pedal to loop his saxophone part while I was looping a vocal part, and they would kind of interplay with one another. And then we had an electric guitarist, Arlo Sims, who would improvise over that."

Under Spalding, Quisol is currently taking a course called "Applied Music Activism." On January 24, the day after a recent class with Spalding, Quisol spotted the singer at a campus protest where 200 student activists had gathered to call for Harvard to withdraw its investments from a hedge fund that holds $1 billion of Puerto Rico's debt. "I had just plugged [the protest] in that class on Tuesday and thought, 'Well maybe some people will show up,'" he says. "And then Esperanza shows up, and she's just chilling in the crowd. So I go up to her and say, 'Hey Esperanza, I'm so glad you made it.'"

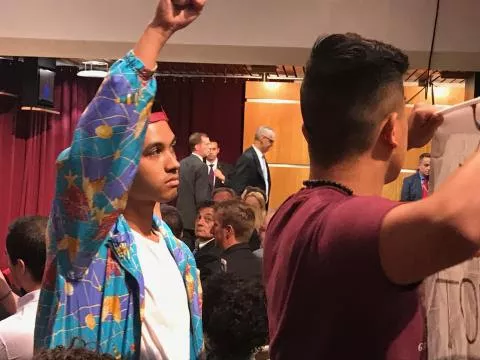

- Quisol (right) holds up a sign protesting a speech by Trump's Education Secretary Betsy DeVos at Harvard in September 2017.

Quisol had been a liaison between Harvard and the Brooklyn-based New York Communities for Change, which organized the demonstration. It was role Quisol became intimately familiar with in Charlotte, where he has served as an organizer with his DIY art group Queens Collective. Last summer, the collective put on a series of pop-up events that brought together musicians and artists in support of local community initiatives ranging from environmentalism to anti-bigotry.

One of the pop-ups supported Bennu Gardens, an urban organic farm on Charlotte's West Side run by Bernard Singleton. Quisol recently released a video that documents his music and community work. "I met Mr. Bernard earlier this year and learned about how he uses the gardens for a youth program," Quisol says in the video.

Singleton explains the purpose of the garden as well as his organization, the CEJS Organic Farms Project. "The garden here is primarily a teaching garden, where we teach horticulture and sustainable living," Singleton says in the video. "Agriculture is art. Every new site I call my blank canvas."

Quisol's political awakening began, of all places, at Charlotte's Mecklenburg Community Church, which, on one hand, does important work with the city's homeless and reaches out to its LGBTQ citizens, but on the other hand, condemns LGBTQ sexuality in its pastor's blog as being against the literal teachings of the Bible.

"My family was going to Mecklenburg Community Church when I was in middle school and high school, and I did music ministry there," Quisol says. "In fact, the first time I ever got on a stage was at that church, doing worship music."

Through the church, Quisol volunteered his time with the poor and homeless in Charlotte, and quickly learned of the demoralization wrought by racism and economic inequality. Then came the controversy surrounding HB2, the notorious N.C. law that sought to define marriage as between a man and woman only.

The political had become personal.

"During my junior and senior year, when HB2 started happening, I started canvassing with organizers," Quisol remembers. "A mentor I had around that time — a school counselor, Bill Strong — told some of us students who were queer that we could help out by asking people to vote against HB2. So that's the first time I got into organizing."

- Quisol (left) and fellow students during the DeVos protest at Harvard.

Quisol chose to study political science at College of Charleston, where he continued to participate in student organizing. "I had begun to connect the dots. I saw that the struggle for queer liberation is connected to poverty, and then learned about world history, studying Southeast Asia, and seeing colonial history and how that's connected back to capitalism, and how Eurocentrism is connected to racism," he says.

"All of these different things, this intersectionality," he says, "showed me how these different struggles are related."

Bringing his growing political awareness into his music has been a slower process. "So far I haven't written political music, explicitly, in terms of my words and content," Quisol says. "But just being a brown person and a queer person, and being visible in this context, is political. Like, my body being at Harvard is political. Or being at Charleston. Existing as me is political."

His words echo those of another group of Charlotte musicians, Blame the Youth — a band made up of black, Latinx, female, transgender and gay members. One member of that group told Pat Moran for a story in CL's Pride issue this past August, "We're political just by existing. It's revolutionary for us just to be in a public space."

Quisol, who considers the members of Blame the Youth friends, concurs. "Some people get uncomfortable when I enter a space because they don't know what to make of me," he says. "I get asked a lot, 'Are you a student here? Can you show your ID?' Especially in Charleston, I would get asked that a lot just going into the honors college dorm. I'm brown, I'm queer, and I was in a top scholars program at College of Charleston. My being there made people look twice and question it.'"

The idea for his forthcoming psychedelic-tinged music video for "Everything and One Thing," Quisol says, was to present himself just as he is — "just me, captured by me, putting my face out there — it's inherently queer and will give people pause just to see a face like mine that they don't recognize as 'the norm.' I definitely think that's inherently political."

As his music continues to develop, Quisol says he expects he'll begin doing more than just alluding to political issues in his lyrics.

"On the action side and the organizing side, I've always been much more explicitly political, and I think as I keep moving forward, the action and music will merge," Quisol says. "I envision my next project being more explicitly political in terms of lyrical content. I have a lot of quotes and recordings saved that I want to integrate into my music. I'm excited to keep creating music that will be more intentionally thought-provoking and challenging for people."

And he will bring the old San Juan that's imprinted in his DNA into his Latinx Future.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Listen to Quisol's The World Keeps Turning: