Ever wonder who's responsible for e-mailing you all that stuff – the Viagra ads, penis enlargement proposals, job offers, pelvic pain remedies and chatty, half-deranged rants?

Sometimes these e-mails don't even contain any words, just Asian-looking symbols. Most are obviously, transparently spam, but occasionally you get tricked by an e-mail that looks real, appears to come from a friend or references something you've just done.

- Splash News

- John Gotti was head of New York's Gambino crime family for six years before being convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment in 1992.

If your spam filter isn't good, you may spend hours each week sorting through it, looking for the few legitimate e-mails that inadvertently seem to end up in your spam folder. And, it seems incredible that people could actually be falling for this stuff.

So who are the brains behind these mountains of spam ... and why do they bother? To understand who they are and what they're up to, you've got to go back seven years, to when things started going badly on Wall Street for organized crime families. Over a nine-month period, federal authorities had busted three of their infamous "pump-and-dump" stock schemes.

In the last of these, Gambino crime family associates and 20 of their employees set up bogus stock brokerages and bought a handful of different stocks. They hired a posse of telemarketers to cold-call victims and hype the stocks. As the victims bought the stocks and drove up the price, the brokerages dumped them, defrauding their victims of more than $50 million.

When the FBI shut the scheme down in 2001, USA Today proclaimed that organized crime's influence on Wall Street was waning -- and it did, for about five minutes.

By 2007 standards, the Gambino scheme was hopelessly primitive. Nobody hires telemarketers or sets up faux brokerages anymore -- and almost nobody gets caught. Instead, today's pump-and-dumpers bombard people's e-mail inboxes with "BUY NOW!" stock tips sent from bootlegged computers in Romania. The Internet analysis company Sophos now estimates that 15 percent of all spam is classic pump-and-dump stock tip fraud, up from .8 percent in January 2005. That's because the scheme works, particularly for fraudsters with the kind of capital to buy hundreds of thousands of dollars of a stock before they pump and dump it. A recent Oxford-based study of pump-and-dump e-mails found that the average cybercriminal can make a 6 percent return in a single day off stock fraud e-mails.

Two years ago, spam was a solved problem, says Daniel Druker, executive vice president of marketing with the spam-blocking company Postini.

"People thought of it as something that was under control," he says. Then, a year ago, it exploded. Over a two-month period this fall, the amount of spam bombarding people's inboxes grew by a staggering 73 percent.

The Internet security company McAfee measures the problem another way. In 2006, McAfee's researchers reported that over 200,000 online threats had been detected. It took 18 years to reach the first 100,000 on record in 2004, McAfee analysts said, and just 22 months to double that figure.

That's because over the last two years, organized crime has begun targeting -- and flooding -- your inbox.

"Computer crime has evolved into organized crime," says Jamz Yaneza, senior threat research analyst at Trend Micro, another Internet security company. "It is no longer the game of individual attackers. The unseen Web threat is maturing, and users should be ever-more careful about what they download and install, as blended threats are ever-more cunning in their attempt to steal corporate and personal data or money."

Five years ago, says Druker, most spam and computer viruses could be attributed to hackers showing off -- guys who had spare time and wanted to show they could bring businesses to their knees and disrupt the Internet. It also came from the kind of annoying and often unscrupulous marketer types who had previously hawked their wares in the junk ad sections of newspapers and porn magazines.

The Can-Spam Act, passed by Congress in 2003, pushed most of these marketers out of the spam business.

"Back in those days you could trace spam back to actual human beings," Druker says. "These were guys that had to buy a computer and rent a server and get an Internet connection and then they'd go send all this stuff out. So the federal government responded by passing this law, and you started to see some convictions."

One of the problems with the old model was that the more spam you sent out, the more it cost.

Then came the botnet, the mother of all criminal vehicles. Hackers had already proved that they could infect people's computers with viruses. But viruses could also be written to string these infected computers together and harness their unused power when they were turned on and connected to the Internet. The owners of these infected machines would never know that while they shopped online or worked on a project for school, their computers were also surreptitiously e-mailing out spam or other viruses to infect additional computers.

For early botnet pioneers, the possibilities for profit were endless. Fraudsters could build botnets that consisted of hundreds or even thousands of computers and use them for their own spam scams, or sell or rent them to others to send out large waves of spam. In the process of taking over a computer for use in a botnet, a virus could also be instructed to raid people's e-mail address books, search for bank records, credit card or social security numbers, even capture every key stroke that a person typed.

Infected computers harnessed by botnets also serve as hosts for fraud schemes.

When an elderly man using a computer for the first time clicks on the link in a spam e-mail to order the Viagra he is afraid to talk to his doctor about, he will be routed to what looks like an online pharmacy to enter his credit card and personal information. But that Web page is actually a fake planted on a botnet computer that will forward his information to the "fraudster" running the scheme and then shut itself down. Again, the owner of the infected computer is almost always none the wiser.

Three to four years ago, most fraudsters were like Shiva Brent Sharma, 22, who is currently serving a four-year maximum prison sentence in New York. Sharma dabbled in a bit of everything. He bought stolen identity and credit card information off the Web and wired tens of thousands of dollars to himself. He bought a program designed to harvest AOL addresses for $60 in a chatroom and used it to collect 100,000 of them for use in a "phishing" scheme in which he sent out e-mails telling people their billing information had been canceled and asking them to re-enter it. He managed to trick over 100 people into entering their financial data on a bogus AOL Web site he set up, Network World reported.

- PATRICK TEHAN

- Postini founder Scott Petry, left, and President and CEO Shinya Akamine, in their Redwood City, California, headquarters. The anti-spam company helps companies cut down on junk e-mail.

Sharma was also among the first in the country to be arrested for Internet identity theft crimes, and the police had relatively little difficulty tracking him down because he did a poor job of laundering his ill-gotten gains and wired some of the stolen credit card cash directly to his own accounts.

Small-time Sharmas are still out there making their living on the Web, experts say, but they are being eclipsed by Internet crime families who hire the Sharmas of the world to help them commit their crimes. Today's phishing schemes involve millions of e-mails, often rely on botnets and are increasingly team efforts. And an entire criminal underworld has developed that specializes in laundering money stolen over the Internet.

So where does all that spam come from? Most computer crime experts point to Russian and Eastern European cybergangs. While the infected computers sending out spam are mostly in the United States, China or a number of Asian countries, the viruses that inhabit them can often be traced to Eastern Europe.

Economics plays a big role in that, says Lance Spitzner, founder and president of the nonprofit Honeynet Project, which tracks criminal patterns on the Web.

"Eastern Europe is actually very highly educated, and many of the Eastern European countries, for example, Armenia, have a higher literacy rate than the United States," says Spitzner. "They also historically and culturally have very strong mathematical skills. So this means you've got quite a breeding ground of very strong, technically competent people. At the same time, Eastern Europe's economy is very bad, so this is one of the few ways that people can make money, is to use their skills."

Combine that with practically nonexistent law enforcement for cybercrime and you've got the perfect breeding ground for Internet crime.

"Not only is the potential return on investment so high, but the odds of them being identified and prosecuted and going to jail in their own country are so astronomically low that it is almost stupid for them to pass up this opportunity," says Spitzner.

Because they have a much better chance of getting caught in the United States, most criminal gangs would rather run a spam scam out of a poor or Third World country. But that doesn't mean that IT students here aren't struggling with smaller-scale temptation.

A June survey of 77 Purdue University computer science students using an anonymous questionnaire found that 88 percent of them had engaged in at least one of a list of online activities that could be described as "deviant" and some that could be described as illegal.

Among the activities on the list was guessing or obtaining another person's password, reading or changing someone else's files, writing or using a computer virus, obtaining credit card numbers and using a device to obtain free phone calls.

The recruitment of these and other Internet technology savvy people around the globe by organized crime to target your inbox in an organized fashion is what is causing the international spike in spam and Internet scams, according to McAfee's 2006 annual Virtual Criminology report.

"Cybercriminals need not only IT specialists -- they need people that can launder money, people that can specialize in ID theft, someone to steal the credit numbers, then hand it off to someone who makes fake cards," says FBI Cyber Division Section Chief Dave Thomas in McAfee's report. "This is certainly not traditional organized crime where the criminals meet in smoky back rooms. Many of these cybercriminals have never even met face to face, but have met online. People are openly recruited on bulletin boards and in online forums where the veil of anonymity makes them fearless to post information."

Although organized criminals may have less of the expertise and access needed to commit cybercrime, they have the funds to buy people with the skills to do it for them, the report says.

The competition for these computer-savvy minds has become so intense among organized crime gangs, that they are using KGB-style tactics to recruit them, including approaching them on campus or at technology conferences and even paying for their schooling, according to the report and the FBI sources quoted in it.

For international criminal gangs, experts say, the lure of easy money online combined with the lack of risk is making cybercrime as attractive if not more attractive than drug-running.

Without a botnet, access to millions of e-mail addresses or help laundering money, Sharma was making $20,000 a day. With those things in place, the possibilities are limitless.

According to Trend Micro's 2006 threat report, organized crime operating on the Internet was the key force behind identity theft, corporate espionage and extortion in 2006. How do they know?

In the new world of Internet crime, the main cops aren't who they used to be and they are not affiliated with the government, at least not directly. McAfee, Trend Micro, Postini and a host of other Internet and spam "protection" companies make their money keeping the Internet usable for millions of people. While they often collaborate with law enforcement to catch the bad guys, mostly these companies block spammers' work by going head to head with them on a daily basis.

Postini fights this war with giant server farms that connect to the Internet from 12 data centers around the world. As Druker explains it, Postini and services like it "sit out on the Internet between your e-mail and the rest of the Internet." All of the e-mail, instant messaging and Web traffic for Postini's 36,000 corporate customers and 10 million users passes through its systems.

"We can tell when there is a computer on the Internet that is sending out a lot of bad stuff all at once, that is exhibiting behavior of a bad guy," says Druker. "By looking in real time and understanding who the bad guys are, where infected computers are, we can block about 60 percent of it without really having to do any work. When we see that happening we will block that same bad guy for all 36,000 customers. It's kind of neat. The bigger we get, the more of the Internet we see and the better our protection is because we are seeing more and more of it faster."

The other 40 percent is trickier. Postini and other companies use computer programs with thousands of rules to decide whether to let other e-mail through. Finally, when spam does get through, employees working around the clock analyze it to figure out why and constantly update the rules to keep it from happening again.

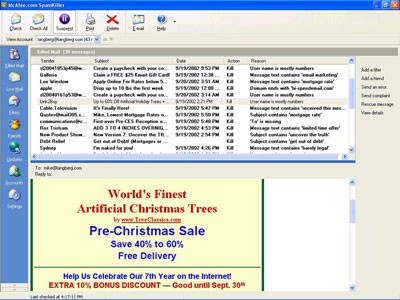

- NEWSCOM

- E-mail filtering programs such as McAfee's Spamkiller can help weed out some of the junk e-mail people receive.

"It's an arms race," says Spitzner. And it is one that has increasingly heated up this year as the combined efforts of organized crime has led to repeated attempts to crash through their walls.

The attacks, Druker says, do follow a predictable pattern. Take the Happy New Year e-mails that went out earlier this month, in the process breaking all records for spam in the December and January months. A virus like that is usually the thunder before the storm, or the first wave of an attack, Druker says, because the virus is infecting computers and being used to build and increase the size of botnets for an inevitable second wave in which a massive spam scheme of some kind is sent over the new channels to the widest possible audience.

Ironically, new schemes that have come to light this fall and winter have led some experts to speculate that volumes may decrease -- and that's not a good thing. That's because cybercriminal families are beginning to show the ability to target specific users who may be more vulnerable to their ads.

Security researchers were blown away by the complexity of the SpamThru Trojan virus that sent a tsunami of spam this fall, including stocks, pills and penis enlargement scams. This fall, a Russian cybergang used the SpamThru Trojan to engineer a tidal wave of junk mail that included everything from stocks to pills. The sophistication of the system that delivered it, which combined 73,000 computers into a single botnet capable of sending out a billion e-mails per day, was unprecedented and contributed to a 60 percent rise in spam during a six week period. So was the virus, which eliminated competing viruses from infected computers and compiled meticulous reports about its infection rates and the location of infected computers and sent them back to the home server, which shifted regularly.

But the most chilling part was the data-mining part of the operation. According to a report by SecureWorks Inc. of Atlanta, the gangsters had hacked into the databases of investment-oriented Web sites to find the e-mail addresses of those who might make the best victims for their pump-and-dump schemes.

While mass-market spam is likely to continue into the future, security analysts say socially engineered spam is now the biggest threat on the horizon. An example might be spam sent only to subscribers of a particular investment service and engineered to look authentic.

Internet security experts are also seeing cybercriminals begin to take advantage of online friends' networks like MySpace to send e-mail to online friends from online friends. So far, these efforts have been fairly easy for the general public to see through, but as they become increasingly sophisticated, that might not always be so.

"Say I want to break into a bank or major corporation like IBM or something like that," says Spitzner. "The easiest way ... to hack into such an organization is you create spam for 300 of the top senior management at said bank, and it looks very real, very professional and if anybody clicks on the e-mail, their computer is hacked. All they need is one percent of those 300 people to click on that e-mail and they're in. So instead of three million people they are going after 300 people."

What happens from there depends on the cybergang's business model. They could steal a company's secrets and sell them to a competitor, blackmail executives, or they could try what is called "spear-phishing." That's where a fraudster who has gained entrance to an organization sends out an authentic looking e-mail from the human resources department asking everyone to immediately fill out a bogus release form that includes the employee's social security number, home address and date of birth and e-mail it back.

Other scams that aren't as targeted are still becoming increasingly creative, says Druker. That's because cybercriminals are now working around the clock. Two to three years ago, it used to be that most spam went out on the weekends, because most fraudsters and virus junkies were part-timers or hobbyists who fooled around one the weekends. Now spam goes out around the clock, every day of the week. That lets them use the news cycle and current hot topics to fool their victims.

"Over the last 60 days, what other trends were they taking advantage of?" asks Druker. "Promoting 'Get a free PlayStation 3' right when they were in demand for Christmas. The Nigerian scheme has now shifted to Iraq. They are just shifting what they do every day to try to make it relevant and topical because they are smart and whatever they can do to make it seem more real to you, they'll do."