The No. 89 jersey has been a top-seller for the Carolina Panthers for several years, worn and adored by Charlotteans and NFL fans around the country. But four years before Steve Smith joined the Panthers, that number was worn by another promising young wide receiver.

After being drafted from the University of Colorado as the 27th pick in the first round in 1997 by the Panthers, Rae Carruth had a great first season. He led all rookie receivers in receptions and receiving yards. The four-year, $3.7 million contract the Panthers signed him to appeared to be a worthy investment. (If Carruth was drafted in the same spot today, he would earn about a $12 million contract, which is what two similar picks were signed to from this year's NFL Draft).

Today though, Carruth is a long way away from that multimillion-dollar lifestyle. He now earns just 70 cents per day working as a barber. And instead of wearing No. 89, for the last eight-plus years he's worn No. 0712822 as he serves out his first-degree murder conspiracy conviction at Nash Correctional Institution in the tiny town of Nashville, N.C.

Though you may have forgotten about him over the years, Carruth was once one of the most famous -- make that infamous -- people in Charlotte. But his notoriety had little to do with his status as a professional football player; instead it grew out of the events of Nov. 16, 1999.

Shortly after midnight on this night, Carruth and his pregnant girlfriend Cherica Adams were leaving the Regal Cinema in south Charlotte. They drove separately, so Adams was following Carruth in her car. Suddenly Carruth stopped in the middle of the road, causing Adams to do the same. A car pulled alongside her and gunshots erupted. She was struck four times -- in the neck, chest, and abdomen. The car carrying the shooter, and two other men, sped off. Carruth drove away as well.

Bleeding profusely and holding on for dear life, Adams was able to call 911, telling the operator that she'd been shot and that she believed Carruth was involved. Police and paramedics arrived minutes later and Adams was rushed to Carolinas Medical Center. Doctors performed emergency surgery to deliver her baby boy, for whom she had already picked out the name Chancellor. He was born 10 weeks premature. After undergoing surgeries and fighting for her life, Adams managed to write notes for the police explaining what happened during her shooting, once again implicating her newborn baby's father.

Based on Adams' accusations and other evidence such as cell phone records, Carruth was arrested for conspiring to commit first-degree murder, attempted murder, and shooting into an occupied vehicle. Also arrested were the three men accused of being in the vehicle from which the gunshots were fired: Van Brett Watkins, the shooter; Michael Kennedy, the driver; and Stanley Abraham, a passenger. Carruth, claiming his innocence, posted a $3-million bond, and it was with the condition that if Adams, who was now in a coma, died, he would turn himself back in to face new charges.

After nearly a month on life support, Adams died on Dec. 14. The charges on the four suspects were upgraded to murder. Carruth, the only one of them who was out on bond, went on the run. The Panthers officially released him from the team. FBI agents tracked him down a couple of days later at a motel in Tennessee. He was discovered hiding in the trunk of a car.

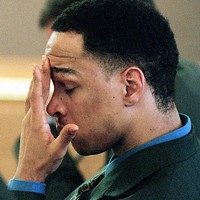

Jury selection began in October 2000 and opening statements for the trial took place on Nov. 20. For the next two months, an intense, emotional, graphic, and, sadly, sometimes comical, trial would play out in front of TV cameras as CourtTV broadcast the proceedings nationwide. "The Rae Carruth Trial" was a murder mystery and soap opera rolled into one.

The prosecution argued that Carruth paid to have Adams killed because he didn't want to pay child support for the baby she was carrying. Carruth was already paying $3,500 a month for a child he fathered a few years earlier. So the thought of adding a second financial burden, after Adams refused to have an abortion, drove Carruth to orchestrate such a callous act, prosecutors contended.

Carruth's defense team, led by Charlotte attorneys David Rudolf and Chris Fialko, claimed that Van Brett Watkins was indeed the guy who killed Adams, but that he shot her in an act of defiance for Carruth backing out of a drug deal that the football star was supposed to finance.

National media outlets -- from ESPN to The New York Times -- found this trial to be sensational, so Charlotte was thrust into the spotlight. The city was still in the early stages of the growth it began experiencing in the late 1990s. The Panthers were midway through their sixth season and many people across the nation were just realizing that the Queen City even had an NFL franchise.

"There was a charged atmosphere around the trial," said Rudolf. "Lots of people were very supportive of Rae. Other people were convinced that he was guilty. Having all the CourtTV people and all the local networks as involved I'm sure raised the intensity of people's feelings."

After a trial that lasted 27 days and featured testimony from 72 witnesses -- including several of Carruth's former lovers and confrontational statements by triggerman Watkins (at one point Watkins called Carruth a "bitch" from the witness stand) -- Carruth was found guilty of conspiracy to commit murder, shooting into an occupied vehicle, and using an instrument to destroy an unborn child. But Carruth was found not guilty of first-degree murder, which allowed him to avoid the death penalty and receive a considerably lighter sentence of 18 to 24 years in prison.

"I continue to believe that Rae was not guilty," said Rudolf, who has represented several high-profile clients, including more recently one of the former Duke lacrosse players who was wrongfully charged in the sex scandal. "I think this was something that Van Brett Watkins organized quite on his own. And I don't think Rae was guilty of even the conspiracy. On the other hand, I think the jury did a very good job of assessing the evidence and finding him not guilty of the murder. Frankly, that was an accomplishment that I'm proud of, to be able to show the jury that he wasn't guilty of the murder. That was important to me."

Carruth was the only one of the four accused men to go on trial. The other three accomplices pled guilty. Watkins accepted a plea deal in exchange for his testimony against Carruth. He pled to charges that included second-degree murder and conspiracy to first-degree murder and was sentenced to 50 years and eight months. Kennedy, the driver, was sentenced to 14 years and nine months, and is projected to be released in 2011. Abraham, the passenger in the car with Kennedy and Watkins, was sentenced to three years and three months, and because of credit for time served between his arrest and conviction, he was released in the summer of 2001.

After the prison gate closed behind Carruth and his accomplices, life went on for everyone else -- everyone except Cherica Adams, who had her life tragically taken away at just 24 years of age. Often lost in high-profile cases like this, unfortunately, are the victims. Cherica was the main victim; another victim was her son, Chancellor, who was born with cerebral palsy, a permanent disorder that can limit communication, cognition, and physical movement, usually caused by a lack of development in the brain during pregnancy. He turns 10 on Nov. 16, sharing a birthday with the day his daddy had his mommy shot. He's being raised by Cherica's mother, his grandmother, Saundra Adams.

"We keep our home filled with pictures of Cherica because she's his mother," said Adams. "He knows that she's his mother and we refer to Cherica as his 'mommy angel.' We talk about her every day and we have a prayer we say every night. Because he has cerebral palsy, I don't think Chancellor's going to understand the details of what happened. But what I tell him about the situation is that he was loved, that he was created in love, and that his dad just did a bad thing."

Chancellor, who attends school in CMS, has braces on his legs and has to use a walker or motorized wheelchair to get around. His speech is limited, but he understands more words than he can speak. He's doing a lot better today than doctors expected when he was delivered 10 years ago during an emergency cesarean section -- skin blue, after periods of not breathing. Doctors told his grandmother that he would probably never be able to walk.

"The prognosis they gave me at birth was that he wasn't going to be doing that well," Adams said. "He suffered a great lack of oxygen at the time that she was shot. They had to go in and somewhat revive him and put him on breathing machines. However since that time, he's doing a lot of physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy. He's saying a lot of words very clearly. His comprehension level is really amazing. He can carry on a conversation with you because he understands what you're saying. He can't always communicate back to you, but we have our own little communication so I understand him."

Adams is remarkably positive when discussing how her life and the life of her family were forever changed. Not only did she lose her only child, but she has to care for her grandson, who requires around-the-clock assistance (she admits to being "overprotective" of Chancellor and doesn't like to ask too many people for help). Time heals most wounds and often makes it easier to deal with tragedies years later, but Adams made an important decision years ago.

"Because I have a very strong Christian faith, it has made it easier for me," she said. "I feel that Cherica is still here in spirit. I see so much of Cherica in Chancellor, so in that sense it has made it easier. I just don't focus on what I've lost; I keep my focus on what I have left, and I make the best of what I have left. Early on, I decided to extend forgiveness to all four of those guys. Not that they asked me for forgiveness, but because I wasn't going to let bitterness and anger imprison me. So I think that made a great difference in how we can go on and live our lives in peacefulness -- Chancellor and I."

Adams, who is involved in victims' rights organizations like Mothers of Murdered Offspring, said there's no communication between her and Carruth, even though she's raising his son.

"Rae was keeping in contact with us somewhat during the early years" she said. "But there's been no communication with him since that time, and that's been roughly five or six years now."

Adams said since Carruth's initial appeal was denied, his family hasn't been involved in Chancellor's life either.

In 2003, Adams won a $5.8 million civil suit she filed against Carruth and the three other men convicted in the case. But with Carruth now broke and spending his most productive years in prison, it's not likely that she'll receive much of the money. Though some small efforts have been made by a very unlikely source.

"Van Brett Watkins is the only one -- I haven't had much communication with him either in the last five years or so -- but he had written me numerous times expressing his remorse and asking for forgiveness. And he was actually trying to pay on the civil suit, whether it be $10, $5, when he would write me, to try to send restitution because he was so remorseful for what he did."

With Carruth's meager prison earnings, according to Keith Acree, public affairs director for the North Carolina Department of Correction, it's a sad irony to think about the NFL money he once made and the millions of dollars he missed out on. He's now 35 years old, and as a wide receiver he could've been nearing the end of a successful playing career. Comparatively, current Panthers receiver Muhsin Muhammad was drafted by the Panthers a year before Carruth, and he's still playing, still earning millions.

Rudolf continues to represent Carruth on appeals. He visits him about three times a year -- most recently three months ago -- and says his client tries not to think about the what-ifs.

"I think he's done his best to get the positive out of his current situation," Rudolf said. "He knows that at some point in the not-too-distant future that he'll be released from prison when his sentence expires. I think it's another eight years, even if the appeal is unsuccessful. A big part of Rae is planning and looking forward to the future when he will be a free person."

Though convictions such as Carruth's are very rarely overturned, he's still fighting it through appeals. Rudolf feels that his client has more leverage after a set of specific rulings by the U.S. Supreme Court.

"Basically, the U.S. Supreme Court has held that you can't use statements that were elicited by the police for [the] purpose of incriminating a suspect against that person at trial," said Rudolf, in regards to the statements Cherica made on her deathbed and how they were the crux of the prosecution's case. "It's just not fair to have a police officer come in and testify about what someone allegedly told them without being able to cross-examine that person. And that's what the U.S. Supreme Court has held repeatedly in the last 10 years, and that was the basis of the appeal."

It's more likely that Carruth will be released sometime around 2019, after having served the majority of his sentence. His son will be a grown man by then -- in age anyway -- not having ever known his father. As cruel and unfair that it is that Chancellor has to live with a debilitating, lifelong condition, perhaps it's a good thing that he may never understand what his daddy did to his mother. That he may never fully realize what his father is most known for.

On Oct. 11, when the Washington Redskins visited the Carolina Panthers, the home team allowed children from the Allegro Foundation to perform on the field during the pre-game activities.

Unbeknownst to members of the Panthers organization and fans in the audience, in the group of about 15 children with disabilities was Chancellor Lee Adams.