The No. 89 jersey has been a top-seller for the Carolina Panthers for several years, worn and adored by Charlotteans and NFL fans around the country. But four years before Steve Smith joined the Panthers, that number was worn by another promising young wide receiver.

After being drafted from the University of Colorado as the 27th pick in the first round in 1997 by the Panthers, Rae Carruth had a great first season. He led all rookie receivers in receptions and receiving yards. The four-year, $3.7 million contract the Panthers signed him to appeared to be a worthy investment. (If Carruth was drafted in the same spot today, he would earn about a $12 million contract, which is what two similar picks were signed to from this year's NFL Draft).

Today though, Carruth is a long way away from that multimillion-dollar lifestyle. He now earns just 70 cents per day working as a barber. And instead of wearing No. 89, for the last eight-plus years he's worn No. 0712822 as he serves out his first-degree murder conspiracy conviction at Nash Correctional Institution in the tiny town of Nashville, N.C.

Though you may have forgotten about him over the years, Carruth was once one of the most famous -- make that infamous -- people in Charlotte. But his notoriety had little to do with his status as a professional football player; instead it grew out of the events of Nov. 16, 1999.

Shortly after midnight on this night, Carruth and his pregnant girlfriend Cherica Adams were leaving the Regal Cinema in south Charlotte. They drove separately, so Adams was following Carruth in her car. Suddenly Carruth stopped in the middle of the road, causing Adams to do the same. A car pulled alongside her and gunshots erupted. She was struck four times -- in the neck, chest, and abdomen. The car carrying the shooter, and two other men, sped off. Carruth drove away as well.

Bleeding profusely and holding on for dear life, Adams was able to call 911, telling the operator that she'd been shot and that she believed Carruth was involved. Police and paramedics arrived minutes later and Adams was rushed to Carolinas Medical Center. Doctors performed emergency surgery to deliver her baby boy, for whom she had already picked out the name Chancellor. He was born 10 weeks premature. After undergoing surgeries and fighting for her life, Adams managed to write notes for the police explaining what happened during her shooting, once again implicating her newborn baby's father.

Based on Adams' accusations and other evidence such as cell phone records, Carruth was arrested for conspiring to commit first-degree murder, attempted murder, and shooting into an occupied vehicle. Also arrested were the three men accused of being in the vehicle from which the gunshots were fired: Van Brett Watkins, the shooter; Michael Kennedy, the driver; and Stanley Abraham, a passenger. Carruth, claiming his innocence, posted a $3-million bond, and it was with the condition that if Adams, who was now in a coma, died, he would turn himself back in to face new charges.

After nearly a month on life support, Adams died on Dec. 14. The charges on the four suspects were upgraded to murder. Carruth, the only one of them who was out on bond, went on the run. The Panthers officially released him from the team. FBI agents tracked him down a couple of days later at a motel in Tennessee. He was discovered hiding in the trunk of a car.

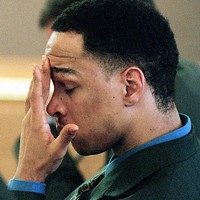

Jury selection began in October 2000 and opening statements for the trial took place on Nov. 20. For the next two months, an intense, emotional, graphic, and, sadly, sometimes comical, trial would play out in front of TV cameras as CourtTV broadcast the proceedings nationwide. "The Rae Carruth Trial" was a murder mystery and soap opera rolled into one.

The prosecution argued that Carruth paid to have Adams killed because he didn't want to pay child support for the baby she was carrying. Carruth was already paying $3,500 a month for a child he fathered a few years earlier. So the thought of adding a second financial burden, after Adams refused to have an abortion, drove Carruth to orchestrate such a callous act, prosecutors contended.

Carruth's defense team, led by Charlotte attorneys David Rudolf and Chris Fialko, claimed that Van Brett Watkins was indeed the guy who killed Adams, but that he shot her in an act of defiance for Carruth backing out of a drug deal that the football star was supposed to finance.

National media outlets -- from ESPN to The New York Times -- found this trial to be sensational, so Charlotte was thrust into the spotlight. The city was still in the early stages of the growth it began experiencing in the late 1990s. The Panthers were midway through their sixth season and many people across the nation were just realizing that the Queen City even had an NFL franchise.