"My biggest concern was that I'd get knocked to the ground and break a finger," artist Dread Scott says above the din of conversation and hip-hop at the McColl Center for Art + Innovation. "But fingers heal."

Scott, named for the famed slave Dred Scott, who unsuccessfully sued for his freedom, is referring to two black-and-white photographs entitled "On the Impossibility of Freedom in a Country Founded on Slavery and Genocide." The photos, which hang in McColl Center's main gallery, depict the artist, 52, withstanding the blast of a high-pressure water hose, the same kind that was trained on men, women and children during the civil rights era, and more recently against the Dakota Access Pipeline protestors. Trapped in the onrushing torrent, Scott's body seems remarkably fragile. I ask if he worried about suffering more serious injuries as the photos were taken.

"Not really," he replies with a wry smile. "Not when you consider the message we need to get across."

That message, a clarion call for protest against the increasingly visible state-sanctioned violence against black Americans — particularly young men — is at the center of The World is a Mirror of My Freedom. The new exhibit combines works from five of McColl Center's current and alumni artists-in-residence, all of them black men, to explore African American masculinity, resistance, and resilience.

On this chilly Friday night, the opening reception is packed with a racially mixed crowd. As people enter the hall, they encounter a quote from singer and civil rights proponent Nina Simone: "An artist's duty is to reflect the times."

- Marcus Kiser and Jason Woodberry's "Pluto"

"The phrase, 'The World is a Mirror of my Freedom,' comes from the French philosopher and political activist Jean-Paul Sartre," says McColl's artistic director Nicole Caruth, who also curates the exhibit. "His meditations on freedom, identity, and the human condition resonated with me." Spurred by police shootings of black men in Louisiana and Minnesota last summer, Caruth began building the show around the work of current artists-in-residence Marcus Kiser and Jason Woodberry.

Kiser and Woodberry's science-fiction musings serve as a launching pad for the exhibit as many younger visitors gather around their bold and whimsical illustrations. A self-professed pair of nerds, Kiser and Woodberry draw from comic books, blacksploitation movies of the 1970s and the gleefully imperialist 1960s cartoon Jonny Quest to depict the interstellar adventures of two black adolescent astronauts, Pluto and Astro.

Viewing the present through a science-fiction filter, Kiser says, makes the country's current situation "more digestible," as police violence against black men becomes more visible. When asked if that violence has been increasing, Woodberry, 33, quotes comedian and activist Dick Gregory: "It's the same song, the rhythm ain't changed."

"The only difference is that everyone with a phone has a camera," Woodbury says. "Everything is being recorded."

Across the gallery, Scott, an artist-in-residence from 2013, concurs. "Courageous people are making cell-phone videos, so everybody knows that this is happening, and many are outraged."

- Marcus Kiser and Jason Woodberry's "I.Matter"

Scott's other pieces illustrate that current outrages draw on a legacy of violence. He's standing in front of "A Man was Lynched by the Police Yesterday," a photographic recreation of a NAACP flag that flew in the 1920s as part of an anti-lynching campaign. Around the corner is a collection of photos and documents entitled "Fragments of a Peculiar Institution." It's an archive of Scott's research into slavery, in preparation for a reenactment of the German Coast Uprising of 1811 in what is now Louisiana.

Speaking by phone earlier in the week, Scott details the event planned for later this year. "It will be a large-scale reenactment of the largest slave rebellion in American history. We'll have 500-plus people in period costume with cane knives, sabers and blunderbusses, covering the span and distance that the original rebellion took outside New Orleans."

Nestled among Scott's photos is one he took across the street from McColl Center in 2013. It's an historic marker noting the final meeting of the Confederate cabinet in Charlotte, just before the close of the Civil War. It suggests how historic attitudes toward slavery continue to taint contemporary society's attitudes toward black Americans.

"The marker mentions 'President' Davis," says Scott, stressing the inclusion of the honorific title. "If I went to Germany, there might be something marking Hitler's last meeting with the Reich, but they wouldn't call him 'Chancellor' Hitler."

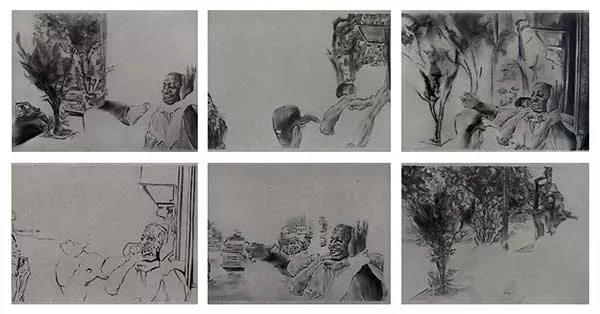

An even more unsettling episode of Charlotte history is noted in the contribution from 2010 artist-in-residence Shaun El C. Leonardo. "It's a brand new series of drawings I did on behalf of Keith Lamont Scott," Leonardo says by phone a day before McColl Center 's open house.

- Shaun Leonardo's "Eric Garner"

Leonardo's series, which marks its world premiere at the exhibit, depicts Scott's fatal encounter with officers of the Charlotte Mecklenburg Police Department, which sparked three days of protests last fall. The artist repeats the same image three times, yet each time the picture is subtly altered. Leonardo, 37, removes information from each iteration, drawing the viewer's eye to different details.

"I'm attempting to slow people's viewing down; give them space within these paralyzing images to just look. Within that space I'm trying to find a way to restore humanity to the image."

Leonardo was unable to attend the opening reception, but he will be at McColl Center on March 18, to present another portion of the exhibit, "I Can't Breathe," a public participation performance that examines the 2014 choking death of Eric Garner by a New York City police officer.

"During the piece, I teach self-defense maneuvers," Leonardo says. "It isn't until I address what I'm teaching in terms of police violence that a different gravity enters the space." When participants feel the weight of an arm around their necks, or the power of a hold, Leonardo explains, they can feel empathy for both victim and perpetrator. He hopes that a crucial moment of vulnerability can be created, a moment that can promote discussion and understanding.

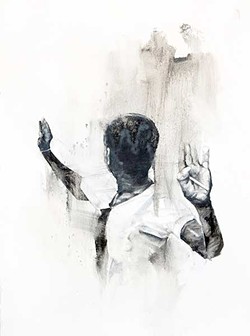

- Charles Williams' "Friday Night, July 24, 1964

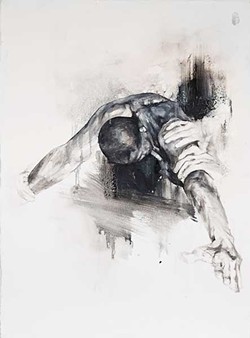

Painter Charles Williams, a 2015 artist-in-residence, also examines Garner's tragic death. Like Leonardo, Williams was unable to attend the exhibit's opening. Speaking by phone the previous day, he says he hopes his work will promote empathy and understanding.

Williams' piece, "Confrontation III," hangs next to the photos of Scott being blasted by the fire hose. In Williams' painting, Garner's outstretched lifeless hand reaches out of darkness toward the viewer. You can barely see his face.

"I wanted to show the vulnerability and the communication of helplessness within the hand," Williams says. "I treat the hand as if it was a portrait."

Hands are important to Williams, who remembers how his grandfather told him to build trust with a firm handshake.

"Hands are the first interaction we have with one another," Williams says, "and we can learn a lot by observing them.

- Charles Williams "Kid with Lucy"

"If you look at black history, we had the black power fist in the 1960s and '70s," he continues. "Now that fist has opened to, 'Hands up, don't shoot.' Where do we go next?"

Wherever we go, the road will likely be rockier under Trump. I recall the words of Scott — whose controversial first major work, "What Is the Proper Way to Display a U.S. Flag?," in 1989, was famously criticized by President George H.W. Bush — from our phone conversation earlier in the week: "What does it mean to have an embodiment of rape culture casting immigrants and people of color as enemies of the state? If artists shut the hell up in the face of this, we will contribute to the darkness that's descending upon society."

The room empties as the opening reception winds down. I take one last look at Williams' painting. Garner's hand still beckons. I remember one more thing Scott said.

"Art by itself is not a revolution, but you can't have a revolution without art."