On a cool April evening in Raleigh, 63-year-old Katie Glover sat down to a meal of vegetarian lasagna and fresh fruit. Glover had come from Charlotte to say goodbye to her little brother, Willie "Junior" Brown, who was scheduled to die by lethal injection at 2am the next morning. Glover would spend the next few hours with Willie Junior, vying for his time with a dozen other family members in the death-row visiting area. But first, Glover, her daughter and her granddaughter shared a quiet meal around the dining room table at Nazareth House, a Catholic Worker hospitality home for death-row families -- and a fulcrum of North Carolina's abolition movement.

- Scott Langley

- Nazareth House, in Raleigh, is a Catholic Worker hospitality home for families of death-row inmates

Among those gathered with Glover at the big round table were Scott Langley and Sheila Stumph, who founded the Raleigh Catholic Worker in a tiny rental house 18 months earlier, and Scott Bass and Roberta Mothershead, who joined with Langley and Stumph and bought this much larger house earlier this year in order to expand the Catholic Worker ministry.

In a few hours, the Catholic Worker activists would join others in trespassing on the grounds of Central Prison to protest the Brown execution. Stumph and Langley had been in court earlier that day with about a dozen other activists who faced charges of trespassing on state property for kneeling to pray in the prison driveway before executions in January and March.

Through these acts of civil disobedience, the founders of Nazareth House, along with several Duke Divinity School students, have been galvanizing members of the statewide People of Faith Against the Death Penalty and other anti-death penalty activists who gather at Central Prison on the nights before every execution. They carry signs proclaiming "Thou Shalt Not Kill" and whisper or shout charismatic prayers begging divine forgiveness for North Carolina's use of "human sacrifice" as an instrument of justice.

Some of the activists fret over how court dates, fines or jail time might affect their pregnancies or vacation plans, but their simple acts have energized an anti-death penalty movement stalled by a partisan split in the state House over what to do about evidence of false convictions, racism and classism in the judicial system. A death-penalty moratorium with wide public support languishes in a legislative committee while a bubble of inmates convicted during the trigger-happy '90s moves through the death chamber. The political wheels have turned too slowly for many of those inmates; 20 have died since the state Senate endorsed a moratorium. Activists such as those who run Nazareth House are trying to grease the gears.

The Catholic Worker movement is a network of laypeople who live in small house-communities such as Nazareth House and two others in Garner and Silk Hope. The movement calls on its members to exercise their Christian duty through political action and personal service to those in need. By offering hospitality to death-row families and helping them speak out against the death penalty, the members of Nazareth House are trying to focus attention on the human beings who suffer when the state chooses to take a life.

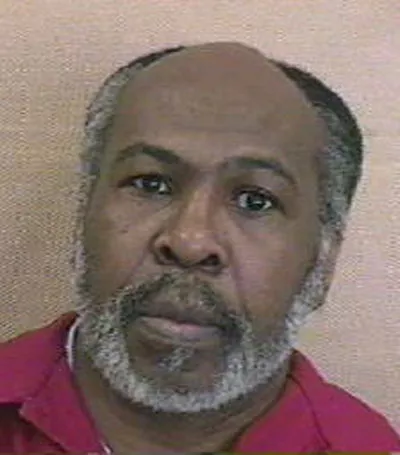

- Willie "Junior" Brown, executed by lethal injection on April 21

Katie Glover and the rest of the Brown family hail from Martin County, about 100 miles east of Raleigh. Glover left North Carolina -- and her Jim Crow bonds -- as soon as she turned 18. She married and raised her children in Stamford, CT, far from the South and its eye-for-an-eye standard of justice. Since 1977, Southern states have been responsible for more than 80 percent of the nation's executions. Only Texas, Virginia, Oklahoma, Missouri and Florida have executed more convicts than North Carolina, and only 11 states have higher execution rates per capita. All but Missouri are in the South. North Carolina's murder rate per capita is twice as high as in Connecticut, where Glover lived most of her life. North Carolina's per capita execution rate is 14 times as high: Connecticut has executed only one murderer in the past 30 years, and North Carolina has executed 43. On average, the 38 states that use the death penalty have a 40 percent higher murder rate than those that don't.

For activists, that's evidence that capital punishment fails to deter violent crime and may, in fact, foster a violent society by modeling violence as a means to solve problems. To Glover, it shows the inequities of the nation's criminal justice system. Same crime. Different sentence. A mere 600 miles up I-95.

"One person lives and one person dies," said Glover, shaking her head, with still a hint of her coastal Carolina drawl. "I just don't understand."

Willie Junior was tried and convicted for robbing a convenience store and kidnapping and murdering the clerk, Vallerie Ann Roberson Dixon, in 1983. At least 490 murders were committed in North Carolina that year; just 11 convicted murderers were sentenced to death that year. Willie Junior beat nearly 50-to-1 odds and became one of them. His chances were even lower than normal, according to a UNC-Chapel Hill study, because Brown was a black man accused of killing another black.

Racism was on Durham activist Beth Brockman's mind as she fueled up for the night's act of civil disobedience, her fourth in the past five months. Brockman, also at the dinner table at Nazarath House, eased into the subject.

"That East Coast along North Carolina has a reputation of being pretty conservative," Brockman said casually to Glover. "Was it that way when you were growing up?"

"Well, things were a lot different, because it was during the time of segregation when I was growing up, when I left home. I think that's why I could never go back and live," said Glover, matter-of-factly. "I love going back to visit, but I don't think I could ever go back and live there. It's a lot of bad memories and stuff."

Glover launched into a story about her neighbor Joe James Cross. Rumors were going around Martin County that Cross had been sleeping with a married white woman, Glover said. A group of local whites surrounded Cross on Route 17. They castrated and murdered him.

- Jesse Deconto

- Willie Brown's family gathered at Nazareth House; from left to right are his sister Teresa Shepard, his niece Regina Diane Glover, his sister Katie Glover, his great-niece Nikki Kendrick, his nephew Angelo Brown, Angelo's wife, Patricia, and Willie's brother Tony Brown

"They got the wrong boy," Glover whispered dramatically. "He used to live one street from me. Nobody was ever brought to justice for that."

"And no apology probably, either," said Brockman.

"They tried," said Glover. "You know, lots of things happened. A lot of talk and a lot of words, but nothing really happens."

Scott Bass let out a low whistle and shook his head. Black folks dying for their purported sins. Guilty white folks walking away without a stain. Such tales are not new to Bass, who grew up in the rural southeastern North Carolina town of Clinton. But they still astonish him.

North Carolina has come a long way since the vigilante injustice of the Jim Crow era. The state's system of justice has changed even since 1995, when death sentences peaked at 34, accounting for about 5 percent of the murders. Since 2002, the state has averaged fewer than a half-dozen death sentences a year. Since the mid-1990s, the number of murders also has dropped, from about 700 a year to slightly more than 500. The state has raised professional standards for capital defense attorneys, abolished the death penalty for the mentally retarded, given prosecutors the option to pursue life sentences in first-degree murder cases, required prosecutors to share all their evidence with the defense team and established a special committee to examine injustice in the death-penalty system, including racial bias.

"That has to do, I guess, with the mind-set, the thought of the folks that are on the jury," Democratic state Rep. Beverly Earle, from Mecklenburg County, said a few weeks after Brown's execution. "You know, you've got to change somebody's whole attitude about race and gender."

Earle cochairs the NC House Select Committee on Capital Punishment. The committee has been meeting each month since December and is taking a break during the summer legislative session, which began May 9. The committee will reconvene next fall. Earle hopes she and her colleagues on the committee will be able to convince the other members of the House to freeze executions and allow time for more in-depth study.

"I'm even more convinced that we need to look at the system and find a way to correct some of what the problems are," said Earle, who also is a member of the Legislative Black Caucus. "Some things, probably, will never be able to be corrected because you're dealing with human beings or attitudes."

Between 1993 and 1997, the death-sentence rate in North Carolina was 6.4 percent when minorities killed whites, 2.6 percent when whites killed other whites and 1.7 percent when minorities killed other non-whites. The numbers show who's important -- and who's dangerous -- in the eyes of the judicial system. They paint the systemic racism in black and white. But to hear about the flesh and blood -- someone's neighbor, or brother -- is to realize that statistics don't begin to tell a real human story.

"So what was Willie like?" Scott Bass asked Glover as the folks gathered at the table nibbled their lasagna.

- Jesse Deconto

- Durham resident Beth Brockman (second from left) discussed legal strategy with Duke Divinity School student Sheila McCarthy while Scott Langley and Sheila Stumph waited for their hearing at the Wake County District Court on April 20; Stumph and seven others would be arrested again that same night.

"Oh, he was, he was a boy, a rough boy. I mean, I mean, rough like you'd get him a pair of pants today, and tomorrow, the next day, he'd have holes in them. You know, back then, you know, you didn't have a whole lot of stuff, so you had to use your imagination if you had to have fun. He climbed trees, rode bikes -- back in the day, you know, the game was cowboys and Indians."

"How do you ride a bike on a dirt road?" asked Glover's daughter Regina, a city girl who grew up in Stamford, CT, and now lives in Charlotte.

"You can ride a bike on a dirt road!" Glover answered indignantly.

"Oh, yeah, if that's all you've got," said Scott Bass, another country boy.

"It's hard to ride it on a gravel road," conceded Brockman, a Mississippi native.

"Yeah, and my father was a believer in boys having bicycles," Glover continued, hitting stride in her family memoir and sparking laughter from Sheila Stumph. "Bicycles -- and every Saturday, a haircut."

"Whoa!" exclaimed Stumph, who comes from a liberal Catholic activist family for whom haircuts were optional.

Glover continued: "He made sure that he took them out every Saturday morning, and if the grandsons were there, too, everybody went and got a haircut. But he believed in them boys having a bicycle. I think they were putting in their head that boys had to have transportation."

A week earlier, Glover had visited Willie at the prison. They reminisced about playing cowboys and Indians and using sticks as horses. Willie couldn't remember if Katie had been part of the games; he thought she was too feminine. She called herself a tomboy who was taller and just as tough as her brother.

"My brother was just like any other brother," Glover said.

After dinner, Glover and her family were soon on their way to the prison, and Scott Bass was sharing her message with two dozen other activists gathered for a 7:30pm prayer vigil at the NC State University Doggett Catholic Student Center near Central Prison. Among the mourners was Patrick O'Neill, a correspondent for the Triangle area alternative paper Independent Weekly. O'Neill had interviewed two of Glover's other siblings, Tony and Teresa, who planned to witness Brown's execution. They told O'Neill that Willie's conviction had devastated their mother, Essie May Brown. She died at 64, a few years after Willie went to death row.

"If Willie is killed tonight, the pain and suffering that his family suffers is going to be just the same as anyone else would suffer," said O'Neill.

- jesse deconto

- Teresa Shepard, Regina Diane Glover and Katie Glover mourn the death of Teresa and Katie's brother Willie "Junior" Brown

Midnight fell. Scott Bass was home from the vigil, which had marched from the Doggett Center to the prison with a police motorcycle escort. Willie Brown's brother Kenny and his fiancée, Cherry, and Willie's sister Dillia and her husband, Kendale, had come back to Nazareth House, too. They were snacking on leftover lasagna at a small table in the kitchen. Bass was chatting with Willie's brother-in-law Kendale, a big, talkative teddy bear with an easy laugh. Kendale had never met Willie and was turned away from the prison visiting area, nixing the last opportunity he would ever have. Bass and Kendale talked about growing up in eastern Carolina and playing pick-up basketball. The conversation lulled, and Kendale asked, "So, how long you been into this here?"

"Oh, well, we've only been in this house since the end of January, and we're still, as you can tell, in the process of fixing some things. But you wouldn't believe how much better it looks already; this ceiling by itself is a miracle," said Bass, pointing at the smooth, white wainscoting that had recently replaced a textured, stained surface patched with duct tape and vinyl siding.

Nazareth House was the result of a recent merger between two different hospitality houses. For the past few years, Bass and Mothershead had been hosting the homeless in their small house on the northern edge of downtown Raleigh. Eighteen months ago, Langley and Stumph had moved from a Catholic Worker house in Boston and opened the Raleigh Catholic Worker to serve death-row families in a rented bungalow near Central Prison. Nazareth House is 4,400 square feet -- bigger than the other two houses combined -- providing more space for more people.

The two couples had looked at the house in early 2005. When the price dropped to $200,000 in January, they made their move. Langley and Stumph had brought their donor network; Mothershead and Bass had paid for the gigantic granite house and brought some extra income from Bass' family-counseling practice. Since January, the two couples, with help from various church and activist groups, have thrown themselves almost full-time into preparing the 57-year-old house for guests, and Bass took Kendale's question as an opportunity to explain their motivation.

"For those of us that live here, it really seems like why we're supposed to be on the earth -- our calling, or whatever you want to call it," he said.

"I really admire that because I don't see a lot of this here," said Kendale.

"No, you don't," said Bass, honestly.

"You really don't," echoed Kendale.

"But you know," Bass continued, "sometimes when you start looking around, you start finding out -- when you start telling people what you're doing -- there's more of it than I would have dreamed."

- jesse deconto

- Sheila Stumph giving a TV interview in front of the statehouse on April 20, pictured with her housemate Roberta Mothershead (center) and Roberta's husband, Scott Bass (left).

In fact, the state of North Carolina has more anti-death penalty activism than any other state in the nation. Nowhere else are civil disobedience actions against the death penalty happening at every execution. Some 1,100 businesses, community organizations and municipalities have endorsed a moratorium on executions until the state can administer them more fairly. Across the nation, just 4,300 such groups have signed moratorium resolutions, meaning that organizations and local governments in North Carolina are responsible for more than 25 percent of the total.

Six years ago, the city of Charlotte became one of the first to endorse the resolution. Moratorium coalitions meet regularly in Mecklenburg and Gaston counties, and Charlotte is one of several cities and towns across the state to host prayer vigils before every execution.

Nazareth House has taken the activism beyond politics and prayer to serve the people most affected by the death penalty.

"There aren't too many that open their doors up like that," said Kendale. "I mean, I really mean that."

"Well," said Bass, haltingly. "Shoot, I wish there was a whole lot more we could do, but -- under the circumstances -- it seems like this is something."

"It's a lot," said Dillia.

"It really is. We're saving a whole lot of hundred dollars tonight," said Kendale, sending a wave of nervous laughter around the table. "That's what it was to rent a room at a hotel."

"Well good," said Bass. "We sure don't want that whole process to stimulate the economy. Spend that money in Williamston and Bertie."

Kendale noticed Bass' wedding band.

"So you're married?" he asked.

After Glover and the rest of the family had left for the prison earlier that evening, Bass' wife, Roberta Mothershead, had fretted over whether to return home after the vigil to comfort the family or risk arrest protesting the execution. She'd written a letter to read to police officers guarding the prison: "We were not present at the scene of Willie's original crime against Vallerie, God rest her soul, and may her family forgive us for failing to protect her! But we ARE present here tonight, my brothers and sisters. We can, tonight, say we will uphold our oaths to serve and protect life."

Mothershead decided to commit herself to civil disobedience because her housemates, Scott Langley and Sheila Stumph, had been in court that afternoon facing the trespassing charges from the two previous protests. The Wake County District Attorney's Office had dropped charges from the group's first demonstration in December but was now threatening jail time for protests in January and March. Mothershead had decided to represent Nazareth House in the current act of civil disobedience in case Stumph and Langley had been put in jail or on probation. But to the activists' surprise, the prosecutors hadn't been ready to try them on the previous charges, and the hearing was postponed until June. So Langley and Stumph, along with a handful of others, decided to mount yet another act of civil disobedience. Even though Mothershead was not absolutely needed, she opted to join them anyway, kneeling in prayer before at least 30 police officers guarding the prison parking lot and trusting that her husband would take care of their teenage son, Grant, and the Brown family.

- Scott Langley

- Sheila Stumph and Scott Bass lighting a candle at a prayer vigil for Willie Brown.

"This was her first time," Bass told Kendale and the others.

"Oh!" gasped Kendale.

"Oh, God!" said Cherry.

"So she's probably in the Wake County Jail right now," said Bass. "It's just a way of saying, 'Look, you know, I mean, it's important to stand there and pray ... but at some point, some folks have said, 'You know, this isn't enough. We've got to do something more.'"

Ever since his earlier dinner conversation with Glover, Bass had been thinking of what he had in common with the Brown family. Just like them, he was one of seven children. Just like them, he rode his bicycle along dirt roads. Just like them, he played basketball with friends. Just like them, he loves his family.

"I was thinking a lot about my family, brothers and sisters, and nephews and nieces," he told Dillia.

"Well, this just seems so unreal," she said of the execution. "It really does. It still don't seem real."

"You're right," said Kendale. "Like something off the television. The whole world is on us tonight. You know what I mean? I mean, it seems like that."

"I hear that," said Bass.

"I wouldn't wish this on nobody, you know what I'm saying? It's a sad situation," said Kendale. "They're not just punishing him, they're punishing his whole entire family, you know?"

Just before one in the morning, Kendale, Kenny and their partners went to sleep in a couple of the bedrooms upstairs in the Nazareth House. Two hours later, after Willie Brown's brother Tony and sister Teresa witnessed his execution, they and a half dozen other family members found a leftover platter of sliced meats and cheeses in the Nazareth House refrigerator and crowded around the dining room table once again.

- Scott Langley

- The crowd protesting the execution of Perrie Dyon Simpson.

"Why kill people who kill people to teach people that killing people is wrong?" demanded Willie's 16-year-old great-niece, Nikki Kendrick, a fiery teenager wearing a brightly colored scarf to hold back her shiny black hair. Nikki lives in Charlotte with her grandmother, Katie Glover, and her aunt Regina. Nikki stewed in her adolescent anger (she had not been allowed to visit Willie because she was on the wrong visitation list); Willie's middle-aged sisters were more concerned with mourning.

"Well," said Glover. "I guess he's ... "

"He's with God tonight," said her sister, Teresa.

"That's right," said Glover's daughter, Regina.

Glover's mind was fixed on the victim's family, whom her mother had known.

"We have ... tried not to do or say anything that would upset her family," Glover said. "And I hope they get some peace from all this, if they truly believe that he's guilty, but I don't see how you can get peace from anybody's death."

After the execution, Vallerie Roberson's husband, William Dixon, had released a statement thanking the state for keeping others safe from Willie Brown and for giving his family closure. He also expressed sorrow for the Brown family.

"It just makes you tired; I don't know what it is," said Glover, who'd been awake for almost 24 hours. "You don't want to go to sleep, but you know you need to lay down."

She tried in vain to send her granddaughter to bed, but Nikki was still fuming over the events at the prison, where she was barred from the visiting room and where a pair of her cousins had taken charge.

"I didn't like the fact that the twins was trying to run everything," she said.

"Don't worry about that," said her great-aunt, Teresa. "We're going to put that behind us because we're going to try to become a family now. We're not going to argue with each other and do stuff like that because, see, that's not what Junior wants us to be; he told me that. He didn't want us to have nothing between us like that, so we're going to forgive whatever, whoever did whatever to you or whatever to me. We're gonna forgive 'em for it, and we're going on, OK? That's what we've got to do, and try to be a family and love each other."

"That's the only way you can live with yourself is to forgive 'em," said Glover.

- Scott Langley being arrested at the protest of the execution of Perrie Dyon Simpson

Her daughter Regina changed the subject. She talked about the high bail set for the death-penalty protesters and the TV cameras that spied them at the prison. Willie's brother Tony and their nephew Angelo discussed whether they should wear neckties to the April 23 funeral. Willie Brown would be buried next to his mother Essie May in the family cemetery in Williamston. His sisters discussed how they should dress Willie, whether he needed a shave, and whether he would need shoes, or would the casket cover his feet? They remembered Brown's neatly pressed coveralls, which the prison refused to let the family keep. They recalled the deep breaths Willie took as the poison entered his veins.

Tony stewed over how the state could wait 23 years to take his brother's life, but said he understood the victim's family's need for revenge. "If somebody hurts my family or something, I'm there in the moment, I'm not saying it's justified, but I could do that probably," he said. "But all these years and waiting? You can't ..." he stammered. "You can't ... What kind of mind you got to do that? Cause to wait, that's another killing there."

Nikki was still not quite ready to surrender her grudge against her older cousins for taking charge of the family gathering at the prison.

"I didn't like that at all," she said.

"I didn't like what they done tonight [executing Willie], but there wasn't nothing I could do about it," said Tony.

"No, nothing in the world we could do," Teresa said softly to herself.

"You know what Uncle Willie Junior said?" Tony continued, counseling his niece. "You know what he said? He said we need to get together, all of us now. That's what he's wishing for. For his family to be together. That's what he wished for. No fighting. He said to be together. One."