Born in Statesville, Hannah Barnhardt grew up in an evangelical Christian family with four sisters who all worked at their parents' 24-hour towing business and attended a tiny private Christian school.

"The learning environment was similar to a religious homeschool, in that it was a very small group and we spent more time studying the Bible and religious concepts than standard educational subjects," Barnhardt says.

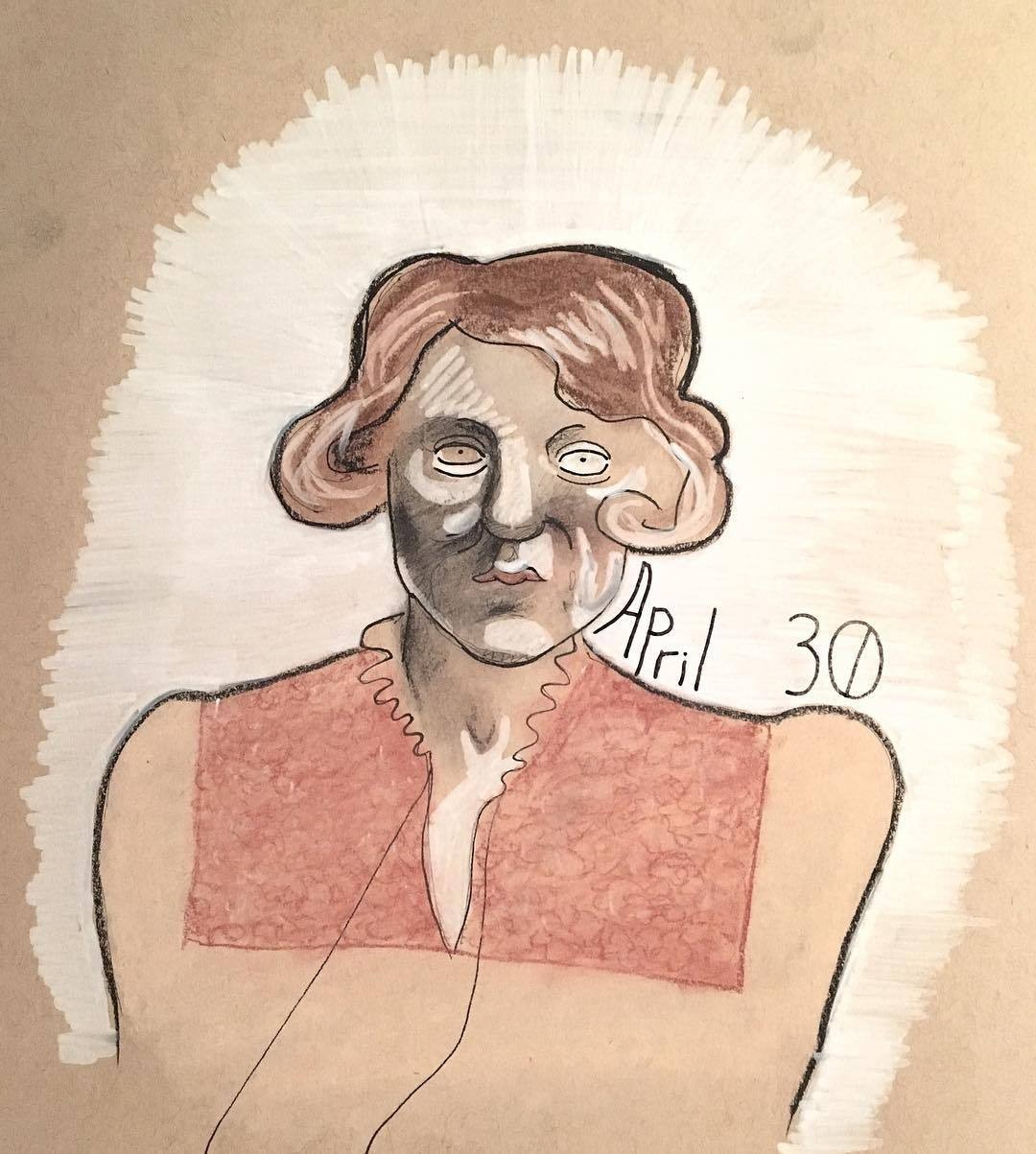

- Hannah Barnhardt (self-portrait)

When Barnhardt and one of her sisters realized they didn't have the proper credits to attend college, the two enrolled into Central Piedmont Community College, using state funding set aside for students in their predicament. Barnhardt eventually was able to get into the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, where she studied anthropology, but she had to drop out of school early due to dwindling funds. She returned to UNC Charlotte in 2013, and graduated in 2016 with a bachelor of fine arts in digital media.

Since then, Barnhardt, 37, has become one of Charlotte's more prolific artists, despite chronic health issues that include symptoms ranging from severe nausea to sleep and mood disorders. For her "Real Charlotte Observer" project alone — in which she uses Micron pens and color markers to draw people at clubs and other social settings — she has filled 28 Moleskine 3.5-by-5-inch blank journals, each containing 192 pages. That's a total of more than 5,300 drawings. "I go through notebooks, pens, and markers like toilet paper. It's terrible," Barnhardt says. "Using the small notebook allows me to move around quickly and get in tight spaces."

For her other projects, including a self-portrait series that verges on performance art, Barnhardt works in photography, video, sculpture, animation, illustration and "projects that straddle the digital and physical world." During our discussions for this week's cover story, Barnhardt and I talked about her Real Charlotte Observer drawings and other projects. This is the unedited version of the shorter Q&A that appeared in this week's print edition of Creative Loafing.

Creative Loafing: We came up with the idea of 'The Melt' when we were talking about you doing this visual story for us. What does The Melt mean to you?

I loved this term that you used to describe the gradual dissolving process that happens [in a club] at a certain hour, as the alcohol and action of the night starts to wear on people. I'm not anti-alcohol, or anti-drug, or even anti-partying; I think there's a place for all that, and I've been in that place and enjoyed it.

I am a former alcoholic, so that definitely shapes the way I see and experience nightlife. Especially after midnight, there's a kind of fraying that happens as people become unraveled. I think for many people who are out in this environment, they're usually pretty inebriated by this point in the night, so their experience of it is different.

How long have you been sketching people in Charlotte's nightclubs and other venues?

I started the project in 2014. Because I don't drink, I didn't spend a lot of time in clubs until 2016. It's not the ideal environment for drawing, as it is understandably more conducive to drinking and dancing. But it's the best place to get drawings of musical acts, and I do want to capture a sense of what the nightlife is like, how people spend their leisure time, so I added that to the project and started going out to these venues regularly, "working the beat," so to speak, to get the story.

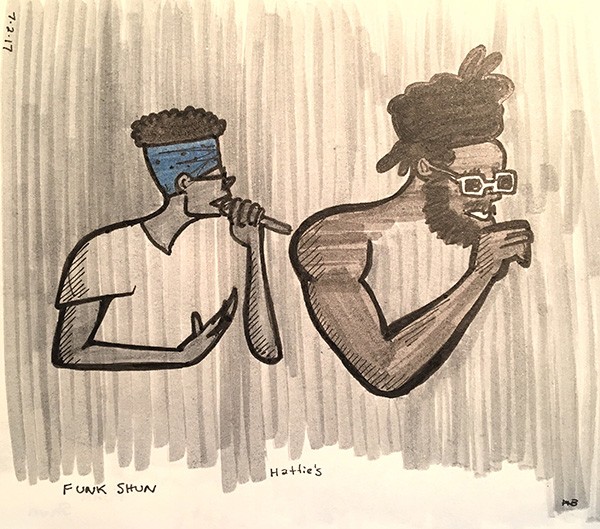

- Real Charlotte Observer: Rappers Nige Hood and Black Linen perform at a Funk-Shun party at Hattie’s. "Oba, one of the organizers of Funk-Shun, has been so supportive of this project and he invited me to the event to draw, which I really appreciated," Barnhardt says. "Nige was already a friend, so I wanted to get good drawings of him on stage, and I got several good ones of Black Linen, too, who I didn’t know at the time, but I had drawn him several times out at events and wanted to see him perform."

What have you learned about people by doing this?

The books and books I could write about all that! I have so much material that can go so many ways, it stresses me out to not be able to pursue it all. When I've worked on this project, the things I learn about people have been profound — and profoundly depressing. I could say a lot about a lot of different things, and those would be complex conversations, but a few random, sweeping observations I would make would be: that people spend an awful lot of time and money to be somewhere only to wish to be somewhere else; that many groups of "friends" have really toxic and arbitrarily hierarchical structures that do not appear to be fun for anyone; that despite our insistence on exercising personal freedom, a lot of people care way, way too much about what other people think about them and are paralyzed by fear.

Many privileged people in Charlotte are either purposefully or accidentally very painfully ignorant of what day-to-day life is like for people who don't have money or access to resources. In particular, middle- and upper-class people seem to take a lot of privileges and resources for granted, as if everyone has savings accounts and tight networks of support consisting of powerful, capable people. As a working-class person on Medicare in a precarious financial and health situation, I am often astounded, embarrassed and then angered at the kinds of cruel and uninformed things that clearly privileged people will say in the open air where anyone can hear them.

- Real Charlotte Observer: Lunchtime crew at Ed's Tavern. "I knew about the history of the place," Barnardt says. "I had never been there before and hadn’t planned on going that day but I had a meeting nearby in the morning that wrapped up right as they were opening. Even though they had just turned their sign on and unlocked the front door, there were all these regulars flooding in, mostly older men, that clearly came there all the time and were waiting for the doors to open, had beers within minutes, bless ‘em. These particular guys were business dudes on their lunch break."

Let's talk a little about your background. Where did you grow up and go to school? What was your family life like?

I was born in Statesville in 1980, and grew up working for my parents' 24-hour towing business that operated out of our home. It's a humble, small-town business, and my sisters and I — there are five of us — did a lot of work to help out. We answered the phones and dispatched calls to dad using radios, and performed other tasks to assist with the daily operations of the business.I convinced my parents to digitize their records in the '90s when I was barely 12, and got them to buy an accounting program, showed them how to use it and how to start entering all their data into the computer to make tax preparation easier and be able to take better control of their finances. I used to drive all around town in my mom's air conditioner-less car collecting payments from vendors and dropping off checks to others. I mostly worked for my family, but I also worked other jobs to help bring in money. In high school, I worked as a soccer referee, a waitress, a beef-jerky salesperson at the Renaissance Festival.

I won't go into the details about why I ended up in a less-than-ideal school situation, because it's a long story, but although I begged my mom to just let me go to public school, my sisters and I attended a very small private Christian school that doesn't exist anymore that was run by and operated in the church we went to at the time — an evangelical congregation in Cornelius called New Beginnings Christian Academy. It was K-12 all in one building, less than 100 kids. My graduating class, including me, consisted of four people.

- A cartoon based on a childhood scenario. "I used to drive my teachers crazy by obsessively yanking on and pulling out my barely loose teeth. I just can’t leave things alone," Barnhardt writes of this piece.

My sister Amy, a year younger than me, was trying during her freshman year to get everything together to apply for college. Our school didn't have counselors or any faculty that helped us prepare for that, so we had to figure all the stuff out ourselves. She discovered that our school didn't offer many of the most basic classes — intermediate and advanced math, science, and foreign language — that we would need to even begin to apply for college. So for three years of high school, I drove every morning from Statesville to Cornelius, dropped my sisters off at school, then Amy and I drove to Central Piedmont Community College uptown and took the classes we needed; we were able to do this for free because of state regulations protecting underage people in our exact situation.

I finished my dual high school studies in 1999, but years later when I was applying for a corporate job, the interviewer who told me I didn't get the position also gave me a heads-up that my diploma from private school got flagged during the background check, and was found to be not valid because the school wasn't accredited. I was able to enroll at UNC Charlotte the fall of 1999 largely because of my sister's diligence in making sure we supplemented our private school with all the coursework at CPCC. I was majoring in anthropology and loving the experience of a real education, learning things that truly interested me, but I had to drop out after two years for lack of money. I've been in the Charlotte area ever since, working retail and administrative jobs. I finally got the chance to go back to school in 2013, and graduated in 2016 with a bachelor of fine arts.

How did the idea of being a sort of artist/journalist/observer occur to you?

As I mentioned, I went back to school in 2013, switching my major to art, something I had always enjoyed but never pursued formally. I never had [art] classes growing up, not even in school, so I had a lot of catching up to do on basic drawing and other skills, and I enjoyed it. I spent hours on introductory drawing assignments, just trying to get up to the level I needed to be. When I took figure drawing, I experienced that spark that many artists do when you realize there's something special about drawing people.

At the time, I had a studio space where I could work at school, and I spent every waking minute there. I rarely left the studio. Even on the weekends, I was there for 14, 16 hours a day. Basically, it was really, really hard for me to leave the studio and stop working, because I loved being buried in my work so much. It still makes me sick to think of how amazing it was to have a space to work! Anyway, because of the way the program is structured, which is attempting to introduce new artists to the idea of an arts community and being active and present in those spaces and institutions, we were encouraged and oftentimes required to attend art shows, openings and other art-related events. While I was genuinely interested in attending these events, I was ultimately always more interested in resuming my own work, and I found myself feeling restless, bored, and leaving quickly so I could get back to the studio, which defeated the networking purposes of these events.

I got into the habit of carrying a small sketchbook with me and drawing whatever was around me whenever I got the chance. I realized that if I focused on live drawing, I could remain present and remain at events, while still indulging in the need to be working constantly. It was fantastic practice for figure drawing; having to make such quick decisions, using pen and being unable to erase mistakes, I improved my drawing skills exponentially because it's such a challenge. It also kept me grounded, present, even hyper-present at these events. It helped me develop a way of being observant, connected to a place and scene, and in the process, finding excitement and meaning in seemingly mundane situations.

Eventually, as I started to get better at it, people who were at the events or in the drawings began to connect with the work, as they function like photographs, as memories of a specific time and place. After a year or so of continuing the project, I realized that beyond serving a therapeutic and skill-improving purpose, it had value on its own as a documentary project. I pursued it more intensely just for the sake of recording life in the city, drawing more often, at a broader range of events, and turning the drawings around to the public faster and trying to distribute them more widely. I think of it as a visual newspaper, focusing on society and culture, sort of like the gossip pages.

- Real Charlotte Observer: It's Snakes perform at Snug Harbor. "This was the first time I saw them, and they kicked so much ass," Barnhardt says. "This was one of those shows where the music is so good that I bounce and tap my foot and have to stop myself from enjoying the music just to get a good drawing. I’m trying to get better at wiggling and drawing, though; it’s good practice."

What artists have you looked to for inspiration?

For my figurative illustrative work, I have this super beat-up paperback of The Phantom Tollbooth that I've pored over since I was a kid, with illustrations by a political cartoonist named Jules Feiffer. Also Aubrey Beardsley, whose work I didn't get exposed to till a few years ago. And early animated cartoons from the 1920s to the '50s. Also Egon Schiele, whose work I didn't realize I knew from growing up watching Aeon Flux, designed by Peter Chung, who was directly influenced by Schiele. And Japanese woodblock prints, with their dark outlines, flattened space, and stylized treatment of the figure and setting. For the figurative photography that I do, I have mostly looked to Francesca Woodman and try to continue her experimental approach to the work.

Aside from your Real Charlotte Observer project, what other media do you work in?

Everything. Photography, video, sculpture, animation, performance, and illustration. I actually consider my best work to be the projects that straddle the digital and physical world, and not my two-dimensional work, and I really intensely enjoy sculptural and performance work in a way that I just don't enjoy other processes. I like using my body, and I am realizing more and more how significant this is to my practice. I've always known I enjoy using my body to work, but now I realize the body is more than a tool and it's about more than being able to use my body to make the work — it's about using my body as the work, as an ever-changing chunk of clay, as a medium in it's own right. I think that whatever my practice is fluctuating around and moving towards, it's headed towards performance.

Can you talk about some of your other projects — for example, your self-portraits?

I do a lot of self-portrait work, and have for over 20 years, but also I'm working on several bodies of work that could best be defined as figurative surrealist narrative still images and moving images. I don't have a lot of opportunities for working with other people (for good reasons, mostly related to my health). I am my cheapest and most available model, who has only as much energy to work with me as I do, and we tire of each other and expire at the same time. So I'm now realizing that some of this work isn't so much self-portraits as they are narratives containing characters that are played and directed by me. I'm trying to separate and organize these personas and pursue those strains in a more focused fashion, and as I do that they begin to flesh out and become more dynamic and real, and new ones introduce themselves. For me, the photo work I've been doing using my figure, usually in a desolate or eroding urban space, is so much fun, it's exhilarating, and one of the few activities that brings me joy. It feels like being in a lab doing experiments and blowing stuff up!

Right now, I have a daily project I've been doing since January 1 that I will continue until December 31: I do a self-portrait every day. At first they started out as ink drawings, but after the first few months I got super bored and started branching out into animations, usually 30- to 60-second animations created in four to six hours in Photoshop. This project, while stupid-annoying at times — because it is every. damn. day. — has spawned so much other work, including the character design for the narrative illustrations I did for Inktober, a worldwide illustrator initiative of creating an ink drawing every day for the month of October. That's been a great way to explore all kinds of basic design lessons for me, things that I still need to catch up on.

- Hanna Barnhardt (self-portrait)

I also have a project I started in school called Selfie Indulgence, where I scanned my body and 3D-printed and molded it, producing plastic copies in various sizes and styles. I haven't had the funds or resources to keep pursuing the physical models of that project, but I have still been modeling content and exploring new things, including pulling printable 3D models of my own skull and abdomen, bones and innards and stuff, from CT scans that I've had over the course of my health problems.

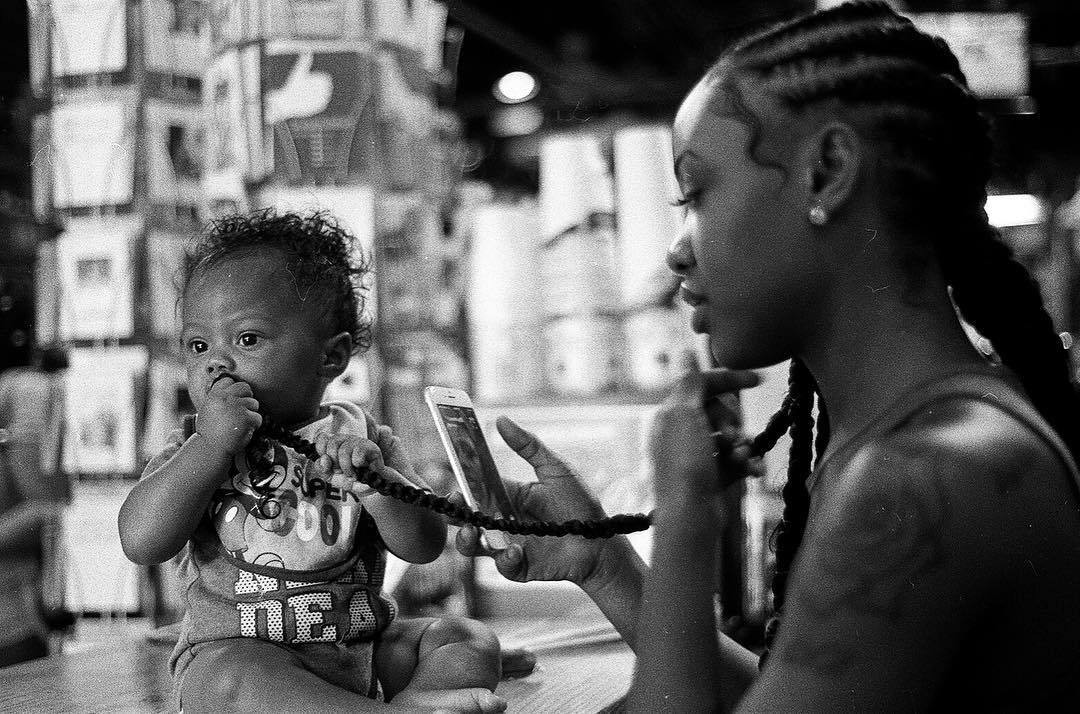

The documentary photo work that I do of people in the city has been going on since I've had my hands on a camera, and I feel compelled to continue it as I do with the drawings: it's a journalistic project that, once it's begun, the momentum of continuing it feeds itself and feels significant in its own right — the longer you do it for a specific place or population, the more of a meaningful archive you collect. I shoot digital as well as black and white film that I develop at home to save money. I've shot a ton of film that has never been scanned or shown, just developed and immediately stored away because I don't have the money to get it scanned.

I have a lot of projects, especially sculptural and film things, that I'm not able to realize because of lack of funds, space, and resources, so I write the ideas down and continue to develop them on paper, organizing the books into sections arranged by medium. I have filled up so many notebooks this way, with what I think are genuinely good ideas that are just waiting for the chance to see the light of day.

- Real Charlotte Observer: Barnhardt's documentary photography: black and white, 35mm film from August 2017 of a moment at Common Market in Plaza Midwood.

What are you trying to communicate in these works?

It depends on the work. So much of my stuff goes in a lot of different directions.

With the Real Charlotte Observer, I'm trying to capture meaningful moments of life in the city that illuminate how people relax, work, eat, travel, converse, argue, laugh, dance, so that it creates a visual history rife with information about all the people details: fashion, music and the culture of the city. With this project I think of the Nina Simone quote about artists having an obligation to reflect the times, and I remind myself that keeping faithful to the project, doing it on a regular basis and dipping into different communities to get a range of life reflecting the city is a worthy goal. What people will get from it varies wildly — it depends on the drawing, and the person. But with this project, I generally see what I'm doing as holding up a mirror, even if it may at times be a funhouse mirror — I'm showing what life looks like in these spaces.

With much of my other work, such as my figurative photography and video work, a lot of those concepts are either discovered as I play in the scene, or they are zapped into my head fully-formed. While there are times where I have a meaning behind a more abstract concept, I don't always know what these visual narratives mean or even what I'm trying to say. I just try to convey it best the way I saw it in my head. I think what's happening in this process is that all of the things I've seen, heard, experienced, and all the media I've consumed over time, gets mushed up and reconfigured in my brain and then spat back out in Frankensteined variations, and I mull through it to see which parts seem most original and feel the most emotionally powerful to me. I can only hope that I've consumed good media, so that the input for own my Frankensteined works was at least good quality before it got churned up.

The thing I have been onto lately is the idea that I can only be who I am, I can only do what I do, and so these strange things that pop into my head, I feel compelled to see them through to the real world. I don't have any pompous notions that these strange things are important, ground-breaking or necessary for the world to see. I just know that if we all have our thing to do, and we're supposed to faithfully and fully do those things, I always have all these things coming to me saying "Make me!" And so that's what I'm going to do, even if I don't always 100-percent know why I'm seeing these things.

What can you convey through your art that you couldn't with words?

It's always weird to try to figure out exactly what it is that is being communicated by an artist. For me, I just seem to experience all the time that what people perceive and what I intended are usually not the same. I used to be frustrated by that, but I am trying to learn from it. The more abstract, or spare, or surreal the work is, the more room it leaves for people to make their own interpretation, for better or worse.

When I do political illustrations that are about local issues that are meant on my part to actually poke somebody or rile someone to be angry about an issue, I don't want there to be any interpretation: I have a specific message, and it's conveyed using a cute illustration to get people's attention, and then WORDS to actually convey the content, so that there's no room for nuance. While I appreciate and still explore this classic method of political illustration, I've been trying to mine my experience drawing people to figure out ways to convey complex political messages using only figures and how they're arranged in the space, and not have to rely on words to communicate.

- Real Charlotte Observer: Then-Charlotte City Council candidate (and now Council Member-elect) Braxton Winston in October.

For The Real Charlotte Observer, I'm more thinking about what the drawings can capture that a photo can't, because otherwise, why spend all this time and effort creating a drawing when a snapshot could serve the same purpose? I also do documentary photography, and I enjoy it. However, it can be very challenging because of issues of consent, space, difficult environments to photograph with no flash, and the uncanny way people suddenly alter their behavior when they see a camera. I found when I started drawing, I was able to get "shots" of people much easier, in much more relaxed and authentic positions.

However, for many compositions, I'm also doing a spectacular degree of stylizing, altering the space, choosing who is shown within the space, heavily stylizing the figure, to create a specific narrative moment, and I think of the drawings as being like photographs that are liberated from the confines of reality. In this way, I can illuminate or add context by choosing how these elements are arranged and presented, in order to communicate the story and feel of the event, and perhaps not necessarily an exact moment that could have been captured by a shutter. I can observe a scene throughout the night and then suddenly create an image that is not at all realistic, could not have been captured by a camera, and yet somehow fully represents real people, from a real moment in time.