- Ripened Peruvian coffee beans. (Photo by Nahun Rodriguez)

"Would you like a cup of coffee?"

It seemed a simple enough question when Matt Hohler posed it at Mecklenburg Market on a recent Saturday afternoon, so I said yes to a sample of robust earthy brew with a slightly bitter bite. It's when I asked Hohler about his business that the gateway opened to the specialty coffee rabbit hole — a world where roasters, regulators, cafes, laboratories and festival organizers strive for two goals: Bringing the consumer a quality cup of coffee, and making sure that as much money as possible finds its way into the farmer's pocket. Creative Loafing discovered that no two participants in the local coffee business follow the same path to quality and fairness.

Hohler and his partner Robert Durrette's commitment to fair treatment for coffee growers is reflected in the name of their company — Farmers First. The Charlotte-based coffee company and roaster trades in specialty coffees from Peru. A specialty coffee is a product graded 80 points or above on a 100-point scale by a taster or grader certified by the Specialty Coffee Association of America, a non-profit trade organization founded in 1982. Consumers pay a premium for specialty coffees, which strive to trace their beans back to a specific microclimate. In contrast, commodity coffee, which comprises less expensive commercial brands like Maxwell House of Folgers, can be sourced from a variety of growing locations.

In 2012, Hohler, who holds a Master's of Public Health Promotion and Education from the University of Toledo in Ohio, was teaching English in Honduras. Coffee plantations and the farmers who worked them surrounded him.

"What it takes to bring a cup of coffee to the consumer is mind-blowing," Hohler says. He saw a disconnect between the hard work and expertise farmers bring to growing, harvesting and drying their crops and how little they were paid. "Most coffee farmers make less than $2,000 per year," Hohler adds.

- Matt Hohler of Farmer's First Coffee. (Photo by Nahun Rodriguez)

At the same time, Hohler met Durrette, owner of the D&D Eco-Lodge in Honduras. Like Hohler, Durrette has also forged friendships with coffee growers and pickers, and he shared Hohler's views on economic inequality in the coffee business. In the summer of 2016, they launched the Levanta Coffee Company. The name, which Hohler says is Spanish for lift up and wake up, proved problematic.

"We realized we were spending too much time explaining the name," Hohler remembers.

Last September they changed the name to Farmers First to sharpen their message, namely their belief that consumers want true transparency behind the products they buy, and that they want to know their money is making a real difference, Hohler says. Fresh out of the gate, the upstart company forged relationships with three Peruvian farmers — Daniel Diaz in the San Martin region, Rosa Lloclla in the Cajamarca region and Emiliano Vilchez in Amazonas. With those three initial producing partners, Farmers First decided to focus on what they call "social microlots," a phrase they coined.

"In coffee parlance, a microlot means that the coffee comes from this one specific farmer — this one producer, on this specific plot of land," Hohler explains.

- Peruvian coffee farmer Rosa Lloclla. (Photo by Nahun Rodriguez)

Social microlot emphasizes Farmers First's socio-economic priorities, a commitment to creating opportunities for their three farming partners to thrive and invest so they could become higher-priced coffee producers in the future, he says. In another break with tradition, Farmers First decided not to apply for fair trade certification.

Most consumers have seen fair trade products in the grocery store, and are aware that fair trade-certified products help secure a better deal for farmers and workers around the world. Fair trade principals and guidelines are administrated and regulated by several non-profit organizations. One of the largest is Fairtrade America.

"The fair trade movement started in 1988, with the first fair trade coffee coming from Mexico," says Fairtrade America's media manager Kyle Freund. "Fair trade continued to grow from there because it asked consumers, 'What are you supporting when you buy?'"

Speaking by phone from his office in Madison, Wisconsin, Freund outlines the key features of fair trade agreements with producers.

- Fairtrade America’s Kyle Freund. (Photo by Paulus Musteikis)

"We're the only certification system that guarantees a minimum price. If you were buying certified fair trade coffee, you have to pay at least that minimum price, which is $1.40 per pound," Freund explains. "The other mechanism we have is the fair trade premium. For coffee, that's an extra 20 cents for each pound of coffee."

Freund stresses that the $1.40 floor price is merely a lower limit, and that certified producers are free to negotiate for a higher price. Certified producers have a safety net, Freund continues. They're paid a set price regardless of market volatility, which could wipe out a small-scale producer. At the same time, the consumer receives a clear signal from the fair trade logo on products in the supermarket. Freund cites Fairtrade America's research that indicates that 55 percent of Americans trust the fair trade label, specifically the green, black and blue label of Fairtrade America.

"It gives consumers a shortcut," he says.

"We in the industry have done a good job of training consumers to recognize and understand those labels," says Counter Culture Coffee's Meredith Taylor. "The average consumer buys coffee at their grocery store along with 25 other things, so they don't have time to research what kind of coffee is best for sustainability." When the fair trade label arose, it clarified a coffee marketplace cluttered with certifications including organic certification and Rainforest Alliance certification, Taylor says.

"No one certification covers everything," Taylor continues. "For example, organic is great if you're concerned about environmental sustainability. It's the same with the Rainforest Alliance. However, neither of those certifications addresses the social conditions or the economic sustainability of growing and selling coffee. Fair trade came in and filled that gap on the social side of things."

- Counter Culture’s Meredith Taylor. (Courtesy of Counter Culture Coffee)

That said, after going the fair trade route since their inception in 1995, Counter Culture, a Durham-based roaster and coffee-education enterprise, stopped buying fair trade certified coffee in 2009.

"We saw a real disconnect, in that fair trade doesn't tie the quality of the coffee to the price of the coffee," Taylor says. High quality coffee takes a lot more labor, materials and time, she adds.

Counter Culture is part of a growing group of companies turning to direct-trade agreements with producers. A key concern for them is that that fair trade-certified coffee is not living up to its chief promise to reduce poverty. Certifications such as organic or fair trade say little about the quality of the coffee or the quality of the lives of the people who have been growing that coffee, says Diana Mnatsakanyan-Sapp.

Mnatsakanyan-Sapp is the director of operations for Undercurrent Coffee, a café and coffee education lab slated to open in Plaza Midwood in May. The lab component of Undercurrent facilitates Specialty Coffee Association of America-approved educational pathways for coffee professionals, including classes for baristas, brewers and more. In addition, she cofounded the inaugural POUR Coffee Festival held in Charlotte earlier this month. Counter Culture participated in the weekend-long event, which celebrated the Southeast's growing specialty coffee culture.

Mnatsakanyan-Sapp maintains that fair trade organizations like Fairtrade America fail to address the entire high-quality crop that specialty roasters pursue and purchase. That situation has led to the development of direct-trade agreements, she says.

- Undercurrent’s Diana Mnatsakanyan-Sapp. (Photo by Elli McGuire)

"Roasters now go to the crop's origin to work alongside farmers," Mnatsakanyan-Sapp says. "They negotiate contracts and enter into deals directly with the farmers." The desired result is that much more of the profit from specialty coffee sales ends up going to the grower, she says.

The goal of getting more money to the farmer is precisely what motivated Hohler to form Farmers First.

On its website, Hohler and Durrette's company posts impact and transparency reports for each of its farmer/partners. In the case of Daniel Diaz, Farmers First paid him a $1.38 gate price per pound of green coffee in 2017. In addition, it paid a 50-percent bonus per pound directly to Diaz, which comes to roughly 75 cents per pound. Hohler contrasts that with fair trade floor prices, which come to $1.40 per pound plus a 20-cent bonus, which goes to a farming cooperative, and not to individual farmers.

Fairtrade America's Freund has no problem with direct-trade deals like Farmers First's agreement with Diaz and their other partners. He compares it to Counter Culture's pioneering direct-trade partnerships which began in 2009.

"What we're seeing there is what we strive for in fair trade relationships," Freund says. "It's a mutually beneficial relationship, where the farmers are treated as if they were partners. They're part of the company vs. just being a supplier."

- Coffee drying on a Burundi hillside. (Courtesy of Counter Culture Coffee)

Freund sees a lot of overlap in the specialty coffee market between fair trade and direct trade, particularly when direct traders follow fair-trade guidelines and work with fair-trade certified cooperatives. For their part, each of Farmers First's farming partners belongs to a local fair trade-certified co-op, Hohler says. In addition to Farmers First's payout to farmers like Diaz, the company also pays an additional 50 cents a pound to each co-op to cover the fees the co-ops pay for fair trade and organic certifications.

But differentiating a direct-trade payout to an individual farmer from a fair-trade payout to a farming co-op is an apples-to-oranges comparison, Freund says. Fair trade focuses on collective organization as much as price, he maintains.

"It's about the power dynamic," Freund says. "That's why we work with cooperatives and farmers organized into those associations."

Farmers are increasingly dealing with bigger trading houses with much more complicated business firms, Freund continues. By organizing together as a co-op, the farmers can be more effective negotiators.

"With co-ops there is a potential for farmers to come together and find access to larger markets," Freund says, and although profits go to the co-op as a whole rather than individuals, co-ops are democratically elected organizations designed to make decisions benefitting their entire communities.

"It's like having a successful company in the community," Freund says. "It goes beyond benefitting just one person."

How much farmers benefit from the coffee business, whether through fair trade or direct trade, is hotly debated. A big selling point for fair trade certification is that it's subject to third-party verification. It's a claim that companies involved in direct trade cannot make. The Fairtrade label on a product means it's been independently checked by FLOCERT, an independent certifier. FLOCERT has suspended and decertified fair trade producers who fail to comply with standards. But many coffee companies have concerns about the transparency of that verification process. "If you go to a fair trade website, you'll be amazed at how little they reveal," Hohler says.

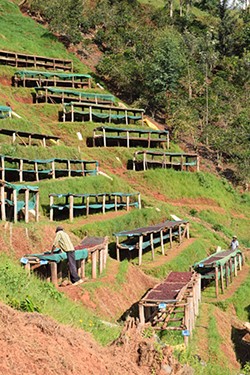

- Drying the coffee beans. (Photo by Nahun Rodriguez)

"Transparency cannot be 100-percent confirmed by third party outside verification," Taylor maintains. In part, difficulties in pinning down the specifics of the verification process are due to all the hands involved in the coffee supply chain — buyers, importers, exporters and roasters. Even the fair trade-mandated floor price of $1.40 a pound is open to debate. "Who knows if people actually pay that price, or if they pay more?" Taylor asks. "There are zero requirements to disclose that."

When Counter Culture Coffee began to transition away from fair-trade certification, it started publishing a transparency report, Taylor says. The report states what the company bought, who it bought from and what the company paid. But even that picture is incomplete.

"When we pay a cooperative, we don't know how much the cooperative is paying the individual farmer," Taylor says. "Up to this point there have been a lot of people working in silence."

Counter Culture has been policing its supply chain, severing ties with importers and exporters unwilling to provide transparency, Taylor says

For the coffee consumer, it all comes down to who you trust, says Mnatsakanyan-Sapp. Despite fair trade's attempt to simplify the certification picture for consumers, shoppers still have to do the work, she says. Consumers have to educate themselves about what the certification labels mean, and then they need to hold the roasters they're purchasing from accountable.

"Just because someone is a local roaster it doesn't mean they're doing the right thing," Mnatsakanyan-Sapp says. "It just means they're in close proximity to where you live."

For its part, Undercurrent partners with Arkansas-based roaster Onyx Coffee Lab, a business Mnatsakanyan-Sapp praises for its transparency.

"They post on their website how much they paid for coffee, what fair trade minimums are for that coffee and that region, and how they invested in the various producers that they work with."

- Coffee drying on raised beds in Burundi. (Courtesy of Counter Culture Coffee)

That said, there is no third party verification for Onyx's claims, and Mnatsakanyan-Sapp believes the onus for determining fairness for coffee growers begins at the grass-roots level. If consumers demand that roasters are held accountable, she maintains, then the roasters will either do the right thing or weed themselves out of the supply chain.

"Typically, things don't change for the better from the top down," Mnatsakanyan-Sapp continues, "but if you start by tending to your corner, it will create ripples outward."

Similarly, Hohler focuses on his piece of the puzzle — three mountainous and geographically separated regions of Peru. When questioned about Farmers First's lack of third-party verification, he counters with company transparency and impact reports, and the stories of his onsite partners — Daniel, Rosa and Emiliano.

"We have proof that we're improving people's lives," Hohler says. "We have this connection, these relationships and these stories, which we're willing to share."

Emiliano Vilchez's story is one of perseverance and hard work. He hails from the village of Otuccho, 4,100 feet above sea level, Hohler says, where he struggles with the effects of climate change on his crop. (The Specialty Coffee Association of America recently published a report that predicted that areas currently suitable for coffee production would be reduced by 50 percent by 2050.) The proudest moment of Vilchez's life was when his daughter was named valedictorian of her high school. He harbored hopes that she would be the first person in her family to go to college.

"There was no way she'd be able to do that," Hohler says. "But with the bonus we're paying, Emiliano was able to take out a loan to pay for her education. He also plans to invest in his farm and pay his pickers more."

Rosa Lloclla, a 42-year old widow with a daughter and two sons, has two children attending college but no electricity in her home, Hohler says. After Farmers First purchased 3,042 pounds of her 5,070-pound crop of green coffee beans and paid her the bonus, Lloclla's annual income increased 79 percent.

"Rosa and her sons bought 2,000 new plants, which has increased their farm size by 25 percent," Hohler says. "They're also building a solar dryer in order to make their exceptional coffee even better."

- Peruvian coffee farmer Rosa Lloclla and son Norberto. (Photo by Nahun Rodriguez)

The most inspiring story may be Daniel Diaz's, Hohler maintains. "He's a leader of his small community Creacion 2000, which he co-founded 18 years ago," Hohler says. "There's a wild mountainous road to the village, and Daniel is one of only three people with a truck." The community depends on Diaz to get up and down the mountain, and to transport its coffee to market. The situation looked dire last year when Diaz's truck broke down because he didn't have enough money to repair it. The bonus paid by Farmers First boosted Diaz's income 61 percent, and it came in the nick time.

"He was able to keep on going, and continue to take care of his community," Hohler says. "75 or 80 cents per pound doesn't seem like much to you or me, but I've seen it have a dramatic impact on people's lives."