- Brad Fanovich hanging in HEX Espresso Bar in South End. (Photo by Ryan Pitkin)

Brad Panovich is a sucker for severe weather.

As a 6-year-old child in Ohio, it was the Blizzard of '78 that inspired him to work in weather. He moved to Charlotte from New Orleans to work as a meteorologist at local NBC affiliate WCNC in December 2002 in the midst of a harsh ice storm that took down more Charlotte trees than Hurricane Hugo. His reaction then was not to wonder what he got himself into. In fact, it was quite the opposite.

"That was my first couple weeks in town and I just fell in love with the city," he recalled. "It's one of the few places I moved to where I felt at home the second I moved here. It just felt right."

Panovich has always felt at home in a weather emergency, he even flew into four hurricanes during his time with WWL in New Orleans. Here in Charlotte, he's gained popularity thanks to his expertise around severe weather. And not in the negative sense, like Nicolas Cage's character in The Weather Man being pelted with fast food, but more like the Penn Station employee in South End who yelled, "That's my weather man," before striking up a conversation with him as we left HEX Espresso Bar on a recent afternoon following Hurricane Florence.

Before that, we sat to chat about the evolution of the American weatherman, internet trolling and climate change denial.

Creative Loafing: How did your fascination with weather come about?

Brad Panovich: It's pretty weird because I knew I wanted to do this when I was 6 years old, and a lot of my friends who are meteorologists are the same way. It's just something early in life that hits you.

For me it was a blizzard, the Blizzard of '78, and we got snowed in at my parents' house when I was a kid and I remember my dad having to climb out the first story window to dig out the front door, and I put my snowmobile suit on, which was standard issue for every Ohio kid, and you go out there and we had six-foot drifts. I was awestruck, and I wanted to know how, what and why that happened.

So from that moment on it was like a light bulb moment, I grew fascinated with bad weather. When there was severe weather I wanted to run outside and look at the sky. I think at some point my parents thought I would outgrow it, but I didn't. I knew from that moment I wanted to be a meteorologist.

I never wanted to be on TV, because growing up, most of the weather people I saw on TV weren't meteorologists. And what I mean by that is they were weather presenters. They didn't have any science back then. They were usually like a failed news anchor or something that they stuck over there, and for me, I loved the science of what I was doing, so I thought I would work for the weather service or NOAA [National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration] or I'd go back to school and maybe be a storm chaser.

So how did you end up on TV?

My senior year at Ohio State [University], there was a hiring freeze in the government, budgets were cut and there's just not enough money. I was like, "Holy cow, what am I gonna do?" So my friend said I should do an internship at the TV station.

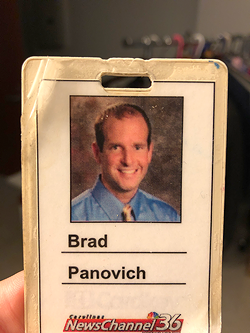

- Panovich still has the badge made on his first day at WCNC on Jan. 1, 2003.

He finally talked me into it, and I did an internship at the CBS station in Columbus, Ohio, WBNS, and I probably should have looked into it more because when I walked in the door, they had their own Doppler radar, they had all these silicone graphic machines that they were building graphics on, and being kind of a tech geek, too, I was like, "Wow this is pretty cool." So I dove headfirst into that.

[Panovich was later hired as the weather producer at WBNS]

It still didn't pay the bills. I had a part-time job at Dick's Sporting Goods. I think [WBNS] were paying me $10 an hour, and I was only working 30 hours a week, this was a part-time thing, and a station in Dayton, Ohio, contacted me and said, "Hey we need a morning meteorologist on air, would you be interested?" That was WKEF. It was an hour and a half way, but they didn't pay me anything, so I basically kept my job at DSG and commuted back and forth.

So I'd do the morning show and I drove back to Columbus and I went to work at Dick's Sporting Goods. I did that for about nine months, but I got a lot of experience on air. I got to cover some tornadoes, every once in a while I would fill in for the chief, so it was really a career builder for me and I was like, "Man, I can do this." I enjoyed it.

You said weathermen were just presenters, not meteorologists, when you were growing up. Has that changed?

It has changed. You cannot get a job in broadcasting now without getting a degree in meteorology or earth sciences of some kind. And you can really put that on the viewers, because severe weather has become so important — the expertise on TV. Anybody can do sunny and 80 degrees. You can hire a model or a funny person to do that, but where people really rely on us is in situations like Florence, or if there's a tornado or snowstorm, and that's where you want the expertise.

Because of the technology we have, most stations spend a lot of money on weather equipment. They spend a lot of money on their weather department. You need somebody with a degree who knows how to use this stuff. And I think because of the internet and social media, people can see through the frauds now. So I think it's a pleasant turn of events that our field has changed almost 180 degrees. There's only a few markets in the country, like Palm Springs and maybe San Diego, where there's not much severe weather to worry about, where entertainment on TV is more important than content.

When you talk about the entertainer as weatherman, it reminds me of watching Mark Mathis when I was growing up in Charlotte.

Yeah, exactly, and that's fun, but the problem we run into with stuff like that is you're trying to serve two different audiences. At one point you're serving one audience while alienating another that wants weather information. So it's a catch-22. Mark used to be a legit meteorologist. He worked at WFAE, he worked at our station back in the day, and he changed his style, and he was very successful at it. And I enjoyed it, I thought it was funny. He catered to an audience that was a non-traditional news audience, but at the expense of the traditional news audience.

So the stations have this constant battle. They sensationalize things to get a certain audience but then do you alienate your hardcore news viewers who understand what you're doing? I sometimes feel like in our industry we shoot ourselves in the foot a lot. We get a sugar rush, we want stuff that happens right now to get a big bump in ratings or a bump in viewers that in the long-term probably hurts our credibility as a source of information.

- Panovich on air in 2009.

We're just coming off Hurricane Florence. Any post-storm insights now that it's past us? Any surprises?

It was a unique storm, and the fact that where it formed in the Atlantic, we've never had a storm hit the east coast in that location. Florence's strength aside, the steering currents were very bizarre.

Most of our storms are re-curving from the south, you think about Hugo, Fran, Hazel, all the big ones people have memories of around here, they came up through the Bahamas and were re-curving, they go through the Carolinas and go back north, this was actually moving east to west.

It was just an odd flow because high pressure is typically centered over Bermuda and the clockwise flow around it steers all the storms that come by the east coast and they go back out. They call it re-curving. And so this one was out in the middle of the Atlantic and backed in from the east to the west and it was a bizarre flow.

It's one of the few hurricanes in our state's history that impacted everybody from the coast to the mountains. This literally impacted the entire state, which is probably why it's going to end up being the costliest hurricane in state history, because it impacted so many people.

You got some trolling over Florence, but even beyond that, weathermen and meteorologists always take a lot of flak from folks who hold them to an impossible standard. Is that something you deal with more now in the social media age?

There's a couple things: social media has changed a lot of things, and people have access to a lot of information. But they don't always know how to interpret that information. I think it's great that people have access to the information but they have to know what they're looking at.

There's certain things that we know as meteorologists, like certain models perform better at this or this or don't on that, or there's sometimes a model in a certain run that's just got a bias or it's doing bad, those are things that are on the fly that we're always interpreting as we go.

So I think access to info has let a lot more misinformation get out there, which is part of the problem.

And then social media, we start talking about systems much earlier than we ever did. Florence is a good example of this. It seemed like I worked forever, but I don't remember ever talking about a hurricane 10 days ahead of time.

With Hugo, you only had a three-day forecast back then, now we have a five-day, so usually if it's in five or six or seven days you might start talking about it, but 10 days out is a long time to talk about a storm and a lot of people think, "Oh my gosh, the forecast changed so much," and I'm like, "Not really." That's sort of typical for something 10 days out.

If you look at any forecast 10 days out, trying to pin down an actual landfall is virtually impossible. So I think there's a combination of just talking about events sooner and people having access to more information.

As far as trolls go, they also have direct access to you on Twitter and other social media sites.

Yeah, and that's good and bad for me. I can be more of an expert and be more active because now I can specify changes and difference in stuff in real time instead of waiting for the 6 and 11 o'clock news, which is that time frame just isn't good for weather, weather is 24/7.

But as far as the trolling thing, I think that's more systemic of what's going on in our society, this anti-science, anti-expert kind of pushback. I don't think they understand the science and expertise of some people, they just feel like everyone's either doing something against them or for them.

It's like people pick sides instead of just making their mind up based on the information.

At the end of the day, the one thing people always need to remember is that we're literally trying to predict the future, and I think it's amazing how well we do that, but I also know it's never going to be 100 percent, and to have that expectation is a false expectation.

Your wife and a group of local mothers created the "I'm a Fanovich" t-shirt campaign to raise money for hurricane relief. How did you learn about that?

Somebody came up with the T-shirt idea. "Let's sell it and we can support Brad, but also support hurricane relief," and all this is going on behind the scenes.

I probably would have known about it if there wasn't a hurricane going on. I was so distracted, and my notifications on my page, my DMs, everything was just blowing up. I haven't been able to keep up with them, and I'm sure if I was I would have been able to pick up on it sooner.

I know someone sent me a screenshot of the T-shirt at some point, and I thought it was just someone who mocked it up in Café Press or something. So that day at the station they come in and surprise me and I'm like, "Oh my gosh." I had no idea all this as going on.

There are many other highly experienced meteorologists in Charlotte. Do you get competitive with your peers?

We don't. We're actually all very close friends. The funny thing about meteorologists, we all have to deal with the same stuff — from crazy viewers, from news directors, from consultants, from all this stuff — and I guess I learned long ago, the reason I do what I do is not really so much for the ratings for the station, I really am trying to serve the viewer.

There are times that people are watching me, there are sometimes that people are watching Eric (Thomas) or Steve (Udelson) or Jeff (Crum). I know when UNC and Duke are playing on BTV, everyone's watching them, so if there was a tornado warning, they're going to get it from them. But Sunday Night Football, or if The Voice is on, I know there's a huge chunk on us. And that changes. That's the nature of viewing habits. So for you to think that everybody's getting information from you is really egotistical and naïve.

We do collaborate behind the scenes quite a bit. We have a private chat with the weather service. In fact, Eric and Jeff Crum and I are actually working on getting a Doppler radar network here in Charlotte, and it's not about the stations or competition, it's about us getting the right info. We all feel a deep connection to that, that this is important for everybody's safety not just for our viewership.

So I think we connect more than some of the news people, honestly, because we have this bond of weather, we love it, and we enjoy it and so we're all a part of the same organizations. We get together every once in a while for lunch and meetings and we're at conferences together, so I can honestly say we're much tighter than I think the stations would like us to be.

Your star has risen in recent years. Do you get recognized on the street often?

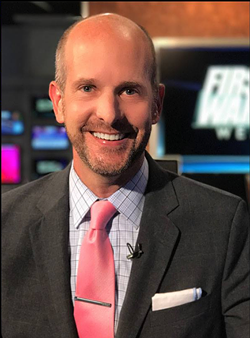

- Current-day Brad.

It's pretty funny, it happens more and more. I get a kick out of the people that don't watch me on TV at all and only follow me online. I think that's only going to keep getting bigger. The thing is, the days of waiting 'til the 6 and 11 o'clock news to get the weather are long gone. So I feel like I've got to be there all the time. One of our neighbors came up to me, she goes, "Hey, are you the weather guy from Twitter?" It wasn't like, "You're the weather guy from CNC or TV," it was, "You're the weather guy from Twitter."

So yeah, that's happening more and more where people recognize me and come up to me. I think the cool thing is people who come up and want to talk the weather. I enjoy talking weather. Where I get weirded out is when people want to talk about TV stuff. "How is this person on TV? Are they nice?" Or they'll ask me about a TV show, and I'm like, "That's not my thing." If it's weather, it's generally what I want to talk about.

You recently posted about the unusual heat in Charlotte this month compared to average September temperatures. Is it disturbing to have this front row seat to climate change?

It's scary but hope is not lost. I think it can be scary if you think about it, if we don't do something about it and we don't change things, but I can also see where we can make a difference.

The frustrating part is, like you just said, I posted a simple thing about September temperatures, it's just stat-based, there's nothing else, there's no interpretation, this is what it is. And immediately you get five or six people, they'll look at a year when it was cool and say, "Oh, where was global warming in 1954?" Well, that was a single year, just like this is a single year, but if I show you the trend over the last 10 years, like seven of the top 10 [warmest years] are in the 2000s.

I try to be apolitical in that sense because it's strictly science to me, and there's no denying the facts. The numbers are the numbers. The numbers don't have a political party. They just are what they are.

We could actually be hotter right now if it wasn't for the Earth trying to counteract some of this stuff. We're in a solar maximum — we're supposed to be — but it's the lowest solar maximum on record. So we actually could be hotter. The sun's really not producing that much heat right now. There are other factors like water vapor, sulfur dioxide, urbanization.

In Charlotte, the easiest argument you can make for manmade climate change is to look at the city; 20-30 years ago there were trees everywhere. Development alone creates heat, creates runoff, it changes our environment. It's not hard to think about that.

I think where people get political is the policy. You can argue the policy, but the cause? It's like me arguing over poverty. Like, "I don't like welfare so I'm going to say poverty doesn't exist." You know? That's why I feel like step one is can we just recognize the problem? It doesn't matter if you're left or right because it's going to take ideas from both sides honestly to solve this.

On a more positive note, what else are you working on for the future of meteorology?

People always ask, "What is the hardest thing about your industry or business?" I think one of the things that I'm finding as I get older and into my career, it used to be the biggest struggle for us was forecasting weather, it still is, but we've gotten pretty good at forecasting. What our hardest problem is now is communicating it.

So I think that's the new frontier for what we do is the words we use, the colors, the graphics, how do we get people to listen to the forecast? Because I think our forecasts are more accurate than they've ever been. The perception that they're not is a problem of communication.

If I look at the duck boat incident in Missouri, there's a severe thunderstorm warning for 45 minutes, why is a boat on the lake? There's this problem with us communicating a threat and people acting on them, so going forward I think that's one of the things I'm working on personally and really have strived as far as research and social science.

There's times when people think that Florence wasn't a big deal. I get upset because how could you not? But part of me is like, I need to understand what kind of information are these people getting? It would be bad for me not to step back sometimes and take a look and listen to even my biggest critics and trolls and say, "Well, why did you think that this wasn't a big deal?"

I think people need to see the bigger picture. And if there's anything I can do to hammer that home, I think that would help. So I'm always learning, that's the great thing about social media. I think people see what I'm pushing out, but what I get back is really important. It really helps me, and it makes me learn about what's working and what's not working from a communication standpoint.