For much of his life, Alexander "Sasha" Ehrenburg dodged bullets and dreaded the knock of the police at his door.

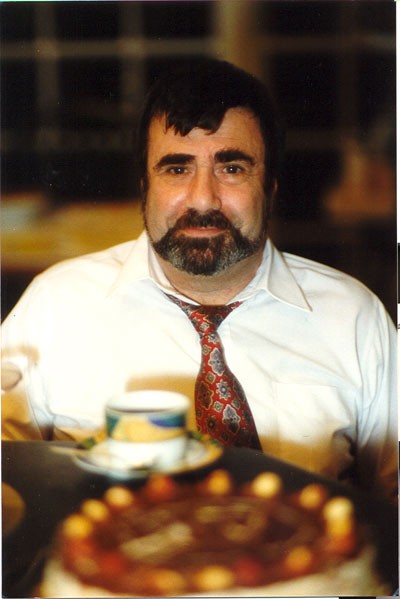

- Courtesy Izabella Skorska

- Friends and family are still struggling to understand why a SWAT team killed Alexander "Sasha" Ehrenburg.

When he was just 4, Ehrenburg, his mother and his baby brother ran from the Nazis, pressing their bodies flat against the grass on the side of the road as German planes attacked from above. Later, he lived with the possibility that the communist police would drag him off the way they did some of his friends, the ones with whom he traded subversive books and dreamed about freedom and an escape to America.

After the Soviets occupied Ehrenburg's native Latvia in 1944, a blanket of dread settled over the country's people. Ehrenburg coped by teaching himself English -- and eventually two other languages -- so he could listen to the broadcasts out of Europe that preached a sermon of freedom. He acquired his vast, encyclopedic knowledge of American history from bootlegged books, any one of which he could have paid for with his life had he been caught reading. Other people he knew disappeared into the Soviet gulag, never to come out again, for much less.

Ehrenburg would later tell the dozens of orphans from former communist republics whom he worked so hard to bring to America about the dreaded knock at the door. It was lecture No. 1, always cued up in Ehrenburg's mind and ready for replay.

"He'd tell them how lucky they were to live in a country where police don't burst into your home and drag you away," says his friend Jeff Barnhart, a state legislator from Cabarrus.

But on May 10, 2005, the police did come for Ehrenburg. They weren't communists, but Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police SWAT officers. And they killed the 67-year-old, wheelchair-bound double-amputee with two shots to his body.

Medics and law enforcement went to Ehrenburg's home that evening not to arrest him, but merely to check on him after a doctor called 911 because he believed Ehrenburg might be having medical problems. Three and a half hours later, Ehrenburg was dead. Though Ehrenburg repeatedly declined their help and asked to be left alone, they knocked down his door twice, and both times officers say he pointed a gun at them. The second time, SWAT killed him.

In the process, it appears police may have violated their own standards for entry -- what few standards they have -- and those policies, experts say, are generally used by SWAT teams across the nation. Worse yet, two versions of what happened that night appear to conflict with one another.

Two years later, friends, family and the doctor who called 911 remain baffled by what happened that evening.

"We were pretty dumbfounded that it had happened," says Dr. David DiLoreto, the doctor who called 911 that night. "We never got a good answer."

In the days after his death, Ehrenburg's wife, Izabella Skorska, was careful not to point an accusing finger at police. Skorska and her husband had been donors to the Police Benevolent Association, and in statements sent to local news outlets, Skorska repeatedly insisted that she supported the police but hoped to get answers soon.

Former Police spokesperson Keith Bridges fired back the day after the shooting, describing Ehrenburg to reporters as a "barricaded gunman" and suggesting that he might have been trying to commit "suicide by cop."

Since then, Ehrenburg's loved ones say that both the police department and the Mecklenburg County prosecutor's office have clammed up and withheld information about the case that could legally have been given to them. Their requests that the North Carolina State Bureau of Investigation be brought in to oversee an investigation into the incident, which is standard practice in the state's other large cities, were ignored.

"If my husband did something very wrong, I would have to accept it," Skorska says.

Instead, a jumble of state and local laws, codes and statutes and the stubbornness of the police department has prevented the family from finding out many of the details about what happened that night.

That set of laws, which Barnhart is working to change in the state legislature, is creating a deadly situation, he says. According to Barnhart, police and SWAT teams can ram down your door and kill you with virtually no public oversight because the public is entitled to very little information about what goes on in these incidents.

Further complicating matters is the general lack of oversight of SWAT teams across the nation.

"There are no national standards, no state standards, no national policy, nothing to regulate these teams," says Peter Kraska, a professor of police studies at Eastern Kentucky University.

"Half in the bag"

Perhaps the most perplexing issue surrounding Ehrenburg's death is why the SWAT team knocked down Ehrenburg's door a second time, just three and a half hours after he pointed a gun at firefighters who burst through his door the first time.

If they knew he had a gun and that he'd already pointed one at firefighters, why ram down his door again and confront Ehrenburg with a gun just to offer him medical help he said he didn't want? Why not wait longer than three hours before doing it? Was this consistent with SWAT policy on forced entry into a home? And what was SWAT policy regarding forced entry?

After multiple e-mail exchanges with police, there are still no clear answers to these questions.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department Major Dale Greene says that the department has no specific policy governing when SWAT makes entry. Instead, officers try to follow state and federal law and their training, which teaches them different tactics for dealing with someone who is barricaded. The department wouldn't elaborate on what these tactics were.

Officers also follow the department's rules on the use of force, which say that when confronted with deadly force, they are justified in using deadly force in return.

Greene initially sent Creative Loafing a memo stating that while there was no specific SWAT policies on entering a home, officers try to follow four "goals." The memo said entry into a building occupied by an armed person should only be done "as a last resort."

"The factors that determine a forced entry depend on the circumstances confronting us," Greene wrote. "For example, a barricaded subject who is threatening to injure or kill a hostage may force us to make entry unlike someone who is alone and intoxicated and has made a vague reference to suicide."

But in a second memo Greene wrote to CL, he said that SWAT broke down Ehrenburg's door to "attempt communication with Mr. Ehrenburg through delivery of a throw phone" after Ehrenburg took his phone off the hook.

Risking the lives of everyone involved in order to toss Ehrenburg a throw phone seems to violate the goals Greene stated for making entry as a last resort.

"I would have to say that the aggressive entry by a SWAT team under those circumstances looks highly dubious," says Davidson College Professor Lance Stell, who teaches bioethics, law and philosophy. "On what possible basis would they be storming the place unless he had a hostage or some innocent person was being threatened by him? They didn't have a reason to think there was innocent life in jeopardy, so it is hard for me to say that that was an exercise of good judgment on their part."

Other questions remain. Why not disable Ehrenburg with tear gas or some other less lethal option, as SWAT has done recently in other situations involving a gunman who was suspected of taking hostages?

Here's what Greene had to say about that: "We did not 'use a gun first,'" Greene wrote. "Officers were constantly asking Mr. Ehrenburg to come out and talk to them. It was only after Mr. Ehrenburg decided to point a firearm at officers that the need to use any force become [sic] reasonably apparent. Up until the moment Mr. Ehrenburg raised and pointed his firearm at officers, there was no objective reason to use tear gas or any other less lethal force."

Greene's answer didn't address the fact that SWAT officers knew Ehrenburg had a gun because he had already pointed it at firefighters a few hours earlier.

Kraska, who studies SWAT tactics across the country, says SWAT teams usually don't burst through doors and confront armed suspects directly unless they pose a danger to others.

"That not only violates most SWAT policies that I'm aware of, it would be highly dangerous knowing there is an armed person in the room and you are going to batter the door down," says Kraska. "That's not smart for the officer himself. That's not a smart use of a SWAT team."

It also wasn't a smart use of a throw phone. It would have been impossible for Ehrenburg, whose legs were amputated at the hip, to bend over and pick up the phone because he would have fallen out of his wheelchair, his wife and friends say.

It's at this point that the two versions of the story -- the one in the official police department statement of relevant facts and another unofficial one on the radio communication tapes obtained by CL -- begin to diverge.

According to the official police statement, once the door was knocked down and the phone was thrown into the darkened living room, police with flashlights talked with Ehrenburg and told him they were trying to assist with his medical condition and weren't there to harm him. Police say Ehrenburg then asked who they were and told them he didn't want to talk to them.

The conversation continued as Ehrenburg moved around the bedroom, police claim, in and out of sight of officers at the front door about 25 feet away. Officers kept asking Ehrenburg to show his hands as Ehrenburg came out of the bedroom into the living room using his wheelchair, the statement reads, narrowing the space between himself and officers at the door to about 18 feet.

"SWAT Officer Kimbell and a second SWAT officer issued commands for Mr. Ehrenburg to show his hands," the statement says. "Mr. Ehrenburg failed to comply with the commands."

There's one major problem with this scenario, Ehrenburg's wife and friends say. Ehrenburg's electric wheelchair was charging in the garage at the time, and he was using the manual one. It would be impossible for him to move forward in his wheelchair without both his hands in plain sight on the wheels. Had he used just one hand, he would have gone in circles.

According to the statement, SWAT officers then noticed a gun in Ehrenburg's lap. They begged him not to reach for it, but Ehrenburg did and "raised the gun with his hand towards the SWAT officers." Kimbell then fired three shots at him, striking him twice and killing him.

That's the official version of events.

In the version of events described on police radio tapes, after SWAT bursts through the door, Ehrenburg is first sitting and then laying down in the living room and no wheelchair is mentioned.

"Right now he is sort of laying down," an officer says on the tape. "They can only see one hand. They are trying to get him to sit up so they can see both hands."

"We can port another window right here and see straight into him," a male voice says.

"Yeah, or you can just (sigh) thinking you can take it to him," another male voice says.

"I think he is half in the bag," the first male voice says. "I don't know if he understands what the hell we're doing here."

"Go in behind the shield," the second male orders and a loud beep then drowns out all other sound for about 20 seconds.

"Alex!" another voice yells. Then another voice orders someone named "Glenn" to "drop a bang" through a back window. A "bang" or "flash bang" is a term for devices commonly used by SWAT teams that are designed to stun and temporarily blind an assailant with a powerful sound and flash of light. One minute and 29 seconds later, officers can be heard on the tape yelling "Medic!"

In the first, official version of events, officers never enter the house, never throw a "bang" and shoot Ehrenburg from the doorway. In the second, unofficial version, they are ordered to go into the house behind a bulletproof shield after the front door is opened.

Four different news reporters at three TV stations and the Charlotte Observer all reported that they were told that SWAT officers shot Ehrenburg after officers entered his condo. Days later, the Observer ran a correction saying that Bridges, the police spokesman, had said the officers never entered the condo.

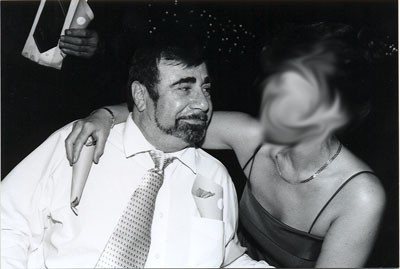

- Courtesy Izabella Skorska

- Alexander "Sasha" Ehrenburg and his wife, Izabella Skorska, celebrate the New Year. Skorska and her husband used to donate to The Police Benevolent Association but she asked us to obscure her photo because she's afraid she'll be targeted if police recognize her in traffic.

Whatever the case, Ehrenburg's death stands out for another reason: Over the last five years, CMPD's SWAT team has intervened in 68 cases, many of them involving criminals who were holed up after they were suspected of committing serious crimes. Ehrenburg is one of only two suspects SWAT has shot during that time and the only one SWAT killed.

Two Sides of a Coin

Ehrenburg's wife and many friends still talk about him with an almost wide-eyed awe and an open admiration for his wicked intellect, which amazed everyone who knew the master's level electrical engineer who worked on nuclear reactors for Duke Energy.

"He was about the sharpest guy we've ever met," says Barnhart, who described being embarrassed from time to time by his inability to keep up with Ehrenburg's vast knowledge of American history and architecture.

His neighbors are still struggling to understand why police killed the man they knew. Ehrenburg was frequently seen piloting his electric wheelchair with an American flag on the back around their Amity Springs Drive area neighborhood off Sharon Amity Road. They say he kept his finger on the neighborhood pulse and always had news to report about what was going on.

He'd warn a neighbor if her car frame looked off balance and was known for fixing and fine-tuning the neighborhood kids' bikes.

"Every kid in the neighborhood liked him," says neighbor Eduardo Romero. "He was always trying to help everybody."

Romero was at home the night Ehrenburg was killed and watched police operate. What he saw angered him.

"The guy was not being a menace to the community," says Romero. "I was more worried about the [police] sniper shooting me than about what was going on."

Several neighbors observed officers laughing and joking around after the shooting as Ehrenburg's dead, uncovered body lay within plain sight in an ambulance nearby.

That didn't sit well with neighbor Veronica Brown, one of those disturbed by police behavior that night.

"They were outside laughing, which I thought was very inappropriate after a man had just died," Brown says. "I'm not saying they were laughing at the situation. I don't know why they were laughing. It just surprised me that they were laughing at a time like that."

In the weeks before he was killed by police, Ehrenburg won a congressional adoption award for his work helping American families adopt children from Belarus, a former Soviet country plagued by a thuggish government and human rights violations after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

In one of the last pictures of Ehrenburg before his death, he is surrounded by Congressman Robin Hayes and some of the children he helped bring to America. Ehrenburg slaved over each one of the 50 adoptions he helped with, translating thick stacks of legal papers from English to Russian and Russian to English for each child. Ehrenburg had also become adept at helping adoptive parents maneuver through the maze of laws they encountered both here and abroad.

Family and friends say that while they are shocked by the outcome of Ehrenburg's encounter with the police, they are not completely surprised by the way others describe Ehrenburg's behavior that evening. Ehrenburg could come across as short and gruff at times, a personality trait that may have ultimately contributed to his death.

The first time Barnhart talked to Ehrenburg about adopting a child, Barnhart says he thought Ehrenburg didn't like him. As he came to know Ehrenburg, Barnhart says he realized it was just a personality tick.

"But if you didn't know him, you would take it personally," says Barnhart.

It was a trait that the dozens of people who came to love Ehrenburg quickly learned to look past, particularly once they realized that it usually stemmed from the sometimes debilitating pain Ehrenburg suffered as part of the vascular disease that cost him his legs. Ehrenburg could be particularly gruff and unresponsive when he didn't feel good.

"He would say, 'I'm sick, sick.' He would say, 'I feel bad,' and then hang up on you," says Barnhart.

Though his doctors encouraged Ehrenburg to take pain medicine and attempted to prescribe it, Ehrenburg refused to take it because he feared it would dull his mind and that, in his drug-induced state, he might embarrass himself, according to his wife and friends.

"Sometimes the pain was really tough," says Skorska.

When the pain hit, he'd shut down emotionally and retreat to his bedroom and the comfort of his electric blanket to fight it alone. It appears that may be what Ehrenburg was attempting to do that evening.

What those close to Ehrenburg can't explain, no matter how many times you ask them, is Ehrenburg's use of his guns, which they say he carried, but never pointed at people. The neighborhood Ehrenburg lived in had been getting rougher for years, and he felt he needed the weapons, a pistol and a shotgun, for protection. Perhaps, they say, he was confused. Perhaps he didn't fully understand what was going on.

Ehrenburg's wife and friends refuse to concede the possibility that perhaps he was being stubborn that night, that he understood perfectly what was going on and in his agitated state couldn't deal with the stress of being told what to do in his own home and threatened police. But they are also emphatic that he had no psychiatric problems. That leaves few logical explanations for Ehrenburg's behavior that night -- or few that they are willing to accept.

But they do admit that he was stubborn. Very stubborn. Ehrenburg had decent grasp of American law, they say; he would have probably believed that he had a right to defend himself against armed intruders and that police and firefighters didn't have a right to enter his house.

The problem is that it appears they did.

"If he is decisionally capable, he can refuse anything doctors offer," says Stell, the Davidson professor who teaches bioethics. "Medic is tricky. When they show up they really have limited discretion. They are supposed to provide emergency care and not stop providing it until somebody with authority tells them to. If 911 gets called and they go to the scene, they are going to be aggressive and they don't really have any discretion to be anything else."

According to the official police statement of facts in the case, after a medic initially spoke to Ehrenburg through the front window around 9:30 p.m. and asked if he needed some help, Ehrenburg said, "Yes." But when the medic asked if Ehrenburg would open the front door, according to the statement, Ehrenburg said, "No" through the window.

Ehrenburg's acknowledgment that he needed help would have given medics and firefighters permission to treat him. In fact, it would have obligated them to.

Firefighters then forcibly popped the front door open with a hooligan tool and saw Ehrenburg sitting in his wheelchair, pointing a shotgun at them, according to the official police statement and medic tapes of the incident. Firefighers and medics then ran from the residence, and Ehrenburg closed and relocked the door.

The statement says that when contact was later made with Ehrenburg by phone, Ehrenburg told police and medic that he "did not want to be disturbed and desired only to go to sleep." It was explained to Ehrenburg that police and medical personnel were there to check his medical condition, the statement says, but Ehrenburg again said that he wanted to be left alone and hung up the phone.

At that point, SWAT was called in and police contacted a magistrate to have Ehrenburg charged with misdemeanor assault by pointing a gun. Since North Carolina law allows police to forcibly enter the residence of someone resisting a warrant for their arrest, the warrant gave police the ability to break down Ehrenburg's door again if they wanted to. But they didn't at first.

Friends and neighbors gathered outside that night say Ehrenburg kept repeating his desire to be left alone, and never claimed he needed help.

Neighbor Carmen Descalzi says that before law enforcement officials shut the neighborhood down and forced her son to come inside, he heard officers and medic communicating with Ehrenburg through the front door of his condo.

"He heard them yelling and him [Ehrenburg] say 'let me go to sleep, leave me alone, I'm tired I want to go to sleep,'" says Descalzi.

Kathy Wert, a friend of the Ehrenburg's, drove to Ehrenburg's home the night of the shooting after receiving a call from Dr. David DiLoreto's wife, Faythe DiLoreto, asking that she check on Ehrenburg. Around 10:30 p.m., Wert convinced police to let her attempt to call Ehrenburg on her cell phone.

When he answered, she tried to talk to him, she says, but she wasn't sure if he knew it was her and after a few minutes the line went dead. Minutes later, when Wert got through to Ehrenburg again, she told him she knew he wasn't feeling well, and he seemed surprised by that.

- Courtesy Izabella Skorska

- A sketch of Alexander "Sasha" Ehrenburg

"He asked me how I knew that and I told him that Faythe had called me," she says. "I asked him if he could just allow the medical people to come in and make sure that he was alright. He said several times that he was tired and wanted to go to sleep."

An hour passed with no attempt at phone communication between police and Ehrenburg. Then, starting at around 11:30 p.m., police called Ehrenburg six more times. Ehrenburg answered the phone the first five times, remaining on the line with police for 20 to 45 seconds each time.

According to the official police statement, Ehrenburg again informed them that he wanted to be left alone so he could go to sleep, then hung up the phone. It's unclear if Ehrenburg did that once or repeatedly during each of the five calls. He didn't answer the sixth call.

That doesn't surprise friends and family either. It was storming that night, and they say Ehrenburg, an electrical engineer, never talked on the phone during a storm because he feared being electrocuted.

They question whether Ehrenburg fully understood the extent of what was going on that night and whether he realized that police were still there after his final phone conversation with them.

Recordings of radio communications from that night refer to about 30 police, fire and medic vehicles being present at one time in front of Ehrenburg's condo. But Ehrenburg couldn't have seen them, because the condo, a back unit, doesn't have a window that looks out onto the street in front of it.

The condo's front door opens out onto a small side lawn. The way the small front porch is positioned, Ehrenburg's view of either side of the alley would have been blocked. He could only have seen a small portion of the side lawn straight ahead and the side of his neighbor's condo.

According to police communications tapes, which are incomplete, police last saw Ehrenburg peek out between the blinds three times between 11:15 p.m. and 11:20 p.m.

The multiple sightings of Ehrenburg and conversations with him through the window bother Skorska the most.

"How dangerous could he be?" she asks.

Skorska says she doesn't believe that anything was physically wrong with her husband that evening beyond his usual struggle with intermittent pain. Had there been, he would have called an ambulance. That's what he did in 1998 when he had a heart attack, she says.

Skorska and her husband had been elated by medical test results Ehrenburg had received at a doctor's appointment the day before the shooting that showed Ehrenburg was in good health and that his condition was stable.

Phone records show Skorska spent half an hour talking to Ehrenburg around 1 p.m. the day he was killed. Her husband sounded fine at the time, Skorska says.

Skorska had been out of town for about two weeks at that point, and says she would never have left the country to visit relatives in Poland had her husband's health been in question.

He was excited about her relatives, who would be returning from Poland with her, coming to visit, she says. In the days before the shooting, he'd gotten his hair cut and hired a maid to clean the house. In her last conversation with her husband, he told her he planned to call Dr. DiLoreto, whom he had never met, to ask for free advice about his kidney because Ehrenburg's HMO wouldn't cover a doctor's visit, Skorska says.

Doctors had told Ehrenburg his kidney was fine, Skorska says, but Ehrenburg wanted a second opinion. He had his other kidney removed years ago after it was discovered he had kidney cancer and feared his one remaining kidney would fail.

Up until that point, Ehrenburg and Skorska had only spoken with Dr. DiLorto's wife, Faythe, about adopting a child. Ehrenburg had never met David DiLoreto, who mispronounced and misspelled Ehrenburg's name during his call to 911.

DiLoreto says that Sasha Ehrenburg sounded fine in the voice mail message Ehrenburg left on the DiLoreto's answering machine at 7:25 p.m. that evening asking David DiLoreto to return his call.

Phone records show that Ehrenburg had spent a considerable amount of time on the phone that afternoon and evening, making and receiving nine calls to and from friends, family and Catholic Social Services after 4 p.m.

But after 7:48 p.m., the phone calls stopped.

When DiLoreto returned Ehrenburg's phone call at 9:12 p.m., Ehrenburg sounded dramatically different than he had on DiLoreto's voice mail earlier that evening.

"He kept repeating, 'I'm so sick,'" says DiLoreto. DiLoreto says he tried to ask Ehrenburg questions, but Ehrenburg wouldn't or couldn't answer them, and instead kept repeating that he was sick. After eight minutes, the phone disconnected, but DiLoreto called back and Ehrenburg picked up again and the two were connected for another eight minutes. DiLoreto says at times he could hear Ehrenburg moving around in the background, as if Ehrenburg had put the phone down. At one point it sounded like Ehrenburg was throwing up.

DiLoreto says he was never sure Ehrenburg knew who he was during either conversation, because Ehrenburg never acknowledged him. DiLoreto told 911 operators that Ehrenburg appeared to be confused, and suggested that he might be in renal failure, but emphasized that he wasn't Ehrenburg's physician and didn't know what if anything was wrong with him. He says Ehrenburg's English wasn't good during their conversation, and he appeared to be slipping back to a Russian language in some places.

DiLoreto says an officer at the scene later called him back that evening, told him Ehrenburg had a gun and wanted to know if Ehrenburg had a psychological disorder.

"I told them he appeared to be confused," says DiLoreto. "I told them he appeared to be a Russian immigrant and that he might be afraid of them because of past experiences with police in Russia. I said he might be more ready to respond to someone speaking his native language."

Policing the Police

Unfortunately, readers of this article now know far more about Ehrenburg's case than the members of Charlotte's citizen review board, which declined to hold a hearing to investigate the case further. The board, which is in charge of investigating complaints about police behavior, is assumed by many to be policing the police.

But as Ehrenburg's case demonstrates, from the beginning, the deck is stacked in favor of the police department.

The board doesn't see actual evidence from cases like Ehrenburg's, but is merely given a summary by the police chief of what happened in the case and other supporting materials if he chooses to provide them. There are no specific rules governing what information must be included in the summary and what can be left out.

Those involved with the citizen review process in this case say review board members never heard the radio communication tapes and largely based their decision off the summary that police wrote up for them.

The Mecklenburg District Attorney's office reviewed the criminal investigations done by the police department in both cases and declined to charge the officers involved with a crime. But aside from county district attorneys, the only eyes that have seen the information that might answer Barnhart's questions belong to those who work for CMPD.

Amanda Martin, an attorney for the North Carolina Press Association, says that while state law doesn't require the police or the district attorney to share the results of their criminal investigation with Ehrenburg or the public, they could if they chose to because the cases are closed.

Given that no criminal charges have been filed against the officer who shot Ehrenburg, it's hard to understand why the police would hesitate to share the results of their investigation with Ehrenburg's family unless they have something to hide, Barnhart says.

While state law forbids the department from sharing information pertaining to the personnel side of the investigation, it could still share most of its case file if it chose to, Martin says.

Barnhart believes that if the full details of the events leading up to Ehrenburg's death were known to the public, and had been scrutinized by the public, cell tower repair man Anthony Wayne Furr, who was shot by police July 2006 after he was surprised while working on a tower off Albemarle Road, might not have been killed.

"I think the biggest thing that happened in Sasha [Ehrenburg's] case was that they surprised him and had that been dealt with, Wayne Furr wouldn't have been surprised," said Barnhart. "I think that's the No. 1 issue. How do you surprise people in their workplace or their living environment and expect them not to react?"