"No Sleep till Brooklyn" could be the soundtrack to the making of Nola Darling's second dance — and to Stacey Rose's journey from the Charlotte theater world to a Spike Lee Netflix joint.

Darling, of course, is the character who made her black-and-white cinematic debut on movie screens across the country in Lee's 1986 full-length film debut She's Gotta Have It. Her story stirred up conversations about female sexual freedom. It challenged gender-role expectations. It prompted conversations about the daily lived experiences of young African-American women.

Nola Darling's story has now been revamped for a 21st century millennial audience whose tastes skew more to on-demand binge-watching. Netflix released the first season of the She's Gotta Have It TV series in November — and Rose contributed her talents to this still-relevant tale of an artistic Brooklynite.

-

Rose (right) with Janelle Williamson of Spike Lee's 40 Acres staff.

Rose served as writers' assistant and script coordinator for the series. From June 2016 to February 2017, the New Jersey-born, Charlotte-schooled playwright pulled all-nighters, taking a no sleep 'till Brooklyn mentality to get the work done. She was tasked with keeping track of the story arc driven by the lead character. Rose took notes in the writers' room, kept tabs on script revisions and got the most up-to-date versions to the production team.

"There were a lot of nights I was not going to sleep until 2 a.m.," Rose remembers of the experience. "I lived in Jersey and had to be back in Brooklyn at 8 a.m. before the writers got there."

For Rose, seeing her name roll in the credits of a series created by Lee, one of her screenwriting idols, was nothing short of surreal. And it would not have happened had she not immersed herself in Charlotte's poetry and theater scenes while finding a path to recovery from addiction. Her experiences as a single mother, divorcée, non-traditional college student and respiratory therapist with a theater side hustle led to Rose's transition out of Hell and into her second career as a full-time playwright.

"Stacey is a phenomenal writer and has been way ahead of her time for a long time," says Quentin Talley, founder of Charlotte's African-American theater company OnQ Productions. "I think she's a visionary. She has work that takes a specific topic and looks at it from a totally different angle."

This week, the Charlotte Arts and Science Council announced it has awarded Rose a grant that will bring her back to Charlotte this summer to facilitate a theater workshop.

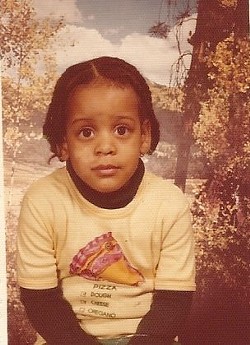

A budding Rose

If anybody knows about the daily lived experiences of a young African-American women, it would be Rose. She grew up in Elizabeth, New Jersey, where the notion of making a living wage from writing plays had never crossed her mind, although teachers throughout her life had made note of her talent. It wasn't until Rose turned 30 that she would see that talent in herself.

- Rosebud: The artist at 4.

As one of four siblings in a single-parent home, Rose saw on a daily basis what it took to provide for a family. "My mother was one of the hardest-working women I ever knew. She started working for Bell Telephone Company at age 16 and did not stop until she retired at 42," Rose says. Having her mom as an example of what hard work looked like, it's no surprise Rose overlooked the idea of the arts being a viable career path.

Still, she was a mere third grader when she was selected to be a part of a special program for bright students. "They put a bunch of black kids from my neighborhood on a bus and shipped us to these gifted and talented schools," Rose remembers.

Had it not been for that opportunity, Rose says, her exposure to the arts would have been limited. "Going to those schools, and not the neighborhood schools, afforded us more engagement with arts and culture," she says.

Her class often took field trips into New York City to see shows. One, in particular, left a strong impression. "The Nutcracker was a huge experience for me," Rose remembers. "I was in awe of the dancing, the costumes and the symphony." It allowed her a space to feel her feelings. "I knew I could be at The Nutcracker and cry just from how the music made me feel. But I never connected it with being anything I could do with my life."

After she left the gifted and talented school program and reached high school, another teacher told the teenager she could make a living as a writer. She didn't believe her. "I was like, 'Oh, that's cute, but I want to make money,'" Rose says.

Two years after graduating from Elizabeth High School in 1994, Rose found her way to Charlotte with her sights set on studying chemistry. What she didn't know is that her own internal chemistry would alter her path.

Party n' Bullshit

After arriving in the Queen City in 1996, Rose eventually enrolled into Johnson C. Smith University. There, an English professor reiterated what Rose's high school teacher had told her: She was a talented writer. But Rose, once again, brushed it off, continuing to study chemistry in JCSU's labs. She also began studying ways to alter her own brain chemistry.

"Addiction snuck up on me," she says. "I was the college party-girl addict. It just built. And built. And built. It progressed from minor weekend hanging out and being social, to [using] every day of the week."

Another internal biochemistry experience changed Rose's course more dramatically. In 1998 she found herself pregnant. The upside was that it put a temporary kibosh on her addiction and gave her a beautiful son, Zion Christopher Rose. The downside is that it also put a kibosh on her plans to get a degree in chemistry.

Rose dropped out of JCSU — pregnant, in a low-paying job, and her child's father long gone. She had to find a way to provide for her new baby as her own single mother, Antoinette Rose, had provided for Stacey and her siblings. She settled on a career in respiratory therapy, because of her history suffering from severe asthma. She enrolled into Central Piedmont Community College's respiratory therapy program, but since she was pregnant, the school suggested she wait.

"I showed up anyway. To hell with that," Rose says. "I was making $7.10 per hour and there was no way in hell I was taking care of a baby on $7.10 per hour."

- Rose, son Zion Christopher and mom Antoinette in recent years.

The Monday after she gave birth, Rose's professor told her she had to be in class the following Monday or get dropped from the program. As a new single mother going to school and working, Rose had to find some way to pull it together. Fortunately, Zion seemed to know innately how to keep his mom sane.

"He was just a good baby. It was uncanny," Rose says. "When I would come home from classes exhausted, he would take a nap. He was just a kid, but he seemed like a soul that had been here before."

She landed her first job as a respiratory therapist at Gaston Memorial in 1999. But by the time Zion was 2, she had found her way back to the party scene and her drug use began to escalate.

"It was not terrible the whole eight years [of active addiction]," Rose says. "All this great shit was happening, [but] then little by little I realized how much I was getting high to cope. It became less about partying and more about entitling myself to a reward. What I did not realize is that I had not given myself a healthy way to cope."

She found ways to function while in her addiction. "I was able to pull my shit together, go to work and not be high," Rose says. "But the rest of the week, it was on." When it came to parenting, she says, "I was present in body. I was present as a parent in all the ways you expect a parent to be, but I was not mentally present. And for me, that is just like telling your child, 'I am leaving.'"

As substance use took Rose to lower depths, she had two motivations that kept her from total demise: Zion and theater. "Being a parent has grounded me to be able to do a lot of the things that I have gone on to do," she says. "For me, if Zion would not have been there — if Zion had not always popped up in my mind as, 'If I fuck up, what is going to happen to Zion?' — I think I would have lost my damn mind. There would not have been anything to stop me."

By 2009 Rose finally found a way to stop. She'd had enough of the deep, dark emotional lows that were only exacerbated by her drug use. She wanted to be present for Zion. On November 10 of that year, Rose got clean. And the sun shone down on her like the swell of strings in a rom-com.

- Stacey Rose stops to smell the… well, you know. (Photo by Jonathan Cooper)

OK, it wasn't really as cinematic as that. Three years before she got clean, Rose had decided to give a shot to the old writing talent her professors had touted. She'd been married briefly and gone through a difficult, emotionally draining divorce. So she began to dip her toes into the theater world.

"It's a weird, fucked-up fairy tale," she says. "I thought art was going to fix me. And I love school, so whenever I feel like the world has its foot on my neck I always feel like I can go to school and study something."

Charlotte Theater

Rose enrolled in English and theater classes at UNC Charlotte and CPCC, where her teachers once again encouraged her to seriously pursue a career as a playwright. This time, she listened. After all, she was now 30 and it was time she pay attention to her inner artist.

From 2006 to 2008, still trying to deal with her addiction, Rose navigated the theater landscape, getting hands-on experience at the Afro-American Cultural Center on Myers Street in First Ward. There, she met Sidney Horton, a longtime fixture of Charlotte's theater community, who pulled Rose into the fold of hosting poetry events. "Those were some good days," she remembers. "My baby was small and would follow me around doing theater. The first few things I wrote were based on that little church [at the Afro-American Culture Center]. Even today I could write something to go into that space. It was my go-to space."

- (Portrait by Jonathan Cooper.)

At the AACC, Rose met Talley, whose then-new OnQ theater group provided her with opportunities to express herself, learn how to make a production work, and put to practice what she studied at UNC Charlotte. "OnQ would produce my shit and respected me as an artist when I did not feel like I was getting any airplay as a playwright in the city at al. Q is the person who always believed in me as an artist," she says, referring to Talley.

For his part, Talley saw a combination in Rose that he coudn't ignore. "She just has a beautiful perspective on things," he says, then pauses. "She also has a hilarious perspective on things."

He cites a specific example of a cutting-edge play by Rose that OnQ produced — The Social NetWorth.

"This was about five years ago, before Facebook and Instagram exploded the way it has now," Talley says. "It was a live theater piece about being online. It was this whole interactive play that could be online and live theater at the same time."

Rose was ahead of the curve, Talley says — too much so for some. "It is plays like that that I believe put her in the forefront of tackling issues that other folks might not be keen on," he says. "And then five years later you're like, 'Oh, that is genius.' But, at the time it may have been too progressive for people. So everybody is catching up to her and she has already been there and done that and is moving on to the next topic."

Bright Lights, Big City

Naturally, a rose has to bloom, and for this Rose, New York City was the next stop. Many of her peers in the local arts scene — Talley, her friend Eric Paulk, who also worked with OnQ, and even CL's current editor, Mark Kemp — strongly pushed her.

"Everybody was like, 'You should be applying to grad school with your level of talent,'" she remembers. "They believed in me more than I did."

With encouragement from her circle of friends — and a distinct lack of support from the Charlotte arts scene at large — Rose enrolled in New York University's prestigious Tisch School of the Arts, got accepted and crowd-sourced a move to the Big Apple. By then, she'd been clean for about four years and had developed healthy coping mechanisms.

- NYC's Playwrights Horizon stages Rose's 'America V 2.1.' (Photo by Stacey Rose)

"I don't ever let myself wallow in disappointment more than 24 hours," she says, using the mantra of recovery. The arts world, as they say, is not for the faint of heart. "In this business you really do have to seek to ground yourself and be OK with yourself," she says, "because the business will not always affirm you."

Rose recalls an opportunity to work with the SoHo Rep Writers Directors Lab. She was rejected. "I was devastated," Rose says, "but in the middle of all this emotional pain I sat up and said, 'Wait a damn minute! I will have been done jumped off a damn bridge if I don't pull myself together.'"

So she did. "Now I am more confident with myself. I know what the hell I want in a way that I never have," Rose says. "I know specifically what I want to do. It is so clear to me now that the things I don't get do not affect me near as much as they did before."

The key, she says, is to allow herself time to mourn: "I give myself a day. I let myself feel it. Then I move on. I got stuff to do. I am 41. I'm an old bitch. I have to get my shit out. I have to get a canon going."

She's Gotta Have It

Rose's time at Tisch taught her many things, not the least of which is how to curate her career as a working writer. And she's now doing it through fellowships, grants and film opportunities — like She's Gotta Have It.

-

Rose with Spike Lee and friends.

One of the more unexpected experiences while Rose was studying at Tisch, she says, was developing a mentor-mentee relationship with Spike Lee, who teaches film at the school. Since she did not study film and did not take classes from Lee, she assumed she'd never come into contact with him.

"Everybody would have these stories: 'Oh, you will see Spike Lee on the elevator, but he is not going to say anything to you,'" Rose says. "I had not seen him and I had not put any faith in seeing him or hoping to build a relationship with him. That just was not my focus. So when I did meet him, it threw me off."

It happened off campus one day at a little sandwich shop around the corner from the school, which is in Greenwich Village at Broadway near Waverly Place. "I was online and my friend was like, 'Spike Lee is behind you.' I was like, 'Yeah right.' And of course I turn around and there he is. He is being haggled by this guy about the Knicks. I was like, 'I am not talking to him. He is going to be aggravated and I am not doing it.'"

Rose's friend kept bugging her: "Oh, you are just going to let him walk away?"

"I was like, 'Yeah, I am going to let him walk away."

Rose did not let him walk away.

"It was so surreal," she says. "I remember it being the windiest day ever. His Knicks hat blew off."

Once she finally spoke to him, Lee had lots of questions for Rose. "He asked me who I was and were I was from," Rose remembers. "He said, 'You should meet my TA — y'all have a similar story' and, 'Come and sign up for advisement.'" That's something Lee does with his students once a week at NYU, unless he's working on a project. "So he walked me up to show me where the sign-up was and closed the door in my face," Rose says. "It was so great."

That connection led to her seat in the writers' room of She's Gotta Have It. She admits it felt pretty weird at first. "Even being in the room did not feel regular," she says. "The first few weeks were like, 'Oh my god...'" She reels off names of famous people. "I'm like, 'Holy shit, how did I end up here?'"

Rose knows exactly how. "Theater got me there," she says. "The long and short of it is: I went to NYU and I met Spike the second semester of my first year there, he took me on as a mentor, he would read my work and we would just talk about things."

It was during those reading sessions that he brought up She's Gotta Have It. "Being who I am, I was like, 'If you have a spot for me...' — not thinking at all that he actually would," Rose says. "But then when the time came, he gave me a call and told me that I would come on as his assistant for the writer's room."

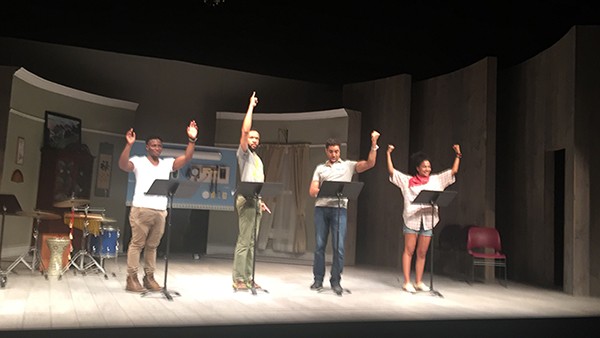

- Rose (second from right) gathers with her fellow playwrights in St. Paul, Minnesota. (Photo Courtesy of the Playwrights' Center.)

Back to CLT

With She's Gotta Have It wrapped and numerous plays of her own under her belt, Rose has curated two more arts opportunities for herself. She is currently a Many Voices Fellow at The Playwrights' Center in St. Paul, Minnesota. And in July, she will head back to Charlotte to facilitate a workshop for her play The Danger: A Homage to Strange Fruit.

The Danger is a thesis play from Rose's days at Tisch that she describes as a "sprawling piece of theater." It examines the legacy of white supremacist patriarchy and violence against black bodies through the eyes of ghosts lost in a dilapidated railroad waiting room set in no particular time period, and trying to find their way out.

But The Danger is more than just a play, Rose says; it is a theatrical symphony structured into four movements. "Each set of characters in the theatrical symphony represents a different set of a musical instruments," she says. "For example, the three mammies represent woodwind instruments."

Not literally, though. "It is building the emotion that a symphony would build," Rose explains. "But instead of instruments, I am using words, bodies and space to create the emotional gravity of a symphony."

Rose was very deliberate in applying for the Arts and Science Council grant to workshop her play in Charlotte. "I want something like this to happen in Charlotte because I rarely see it happen there," she says. "You rarely see a complex piece of theater coming together — not just text, but movement and music."

From July 8 to July 14, Rose will tweak her play-in-progress using feedback from local community members, artistic peers and experts. She will also host dialogue sessions on violence against black bodies.

"My hope is to have it in the West Charlotte community, and bring in people who often do not interact with that community," Rose says. "I think people have to be in the same space. They can't view each other through newspapers. They have to be in the same space experiencing something together."

With the help of this diverse group of Charlotte artists and community members, Rose will learn how the piece works on stage before she debuts it in Brooklyn next fall. Yet again, her theatrical experience in Charlotte will inform her theatrical growth in New York.

"I have not been in a room with this play for a long time," Rose says. "So Charlotte will get to be in a room with me while I am in a room with this play." She pauses. "No matter where I go," she says, "my artistic heart always beats strongest in Q.C."

- The Rose (Photo by Jonathan Cooper)