Sixteen-year-old Blake Brockington was leaning against a doorway when I first saw him in 2013. I was there to teach a creative writing class to young people at Time Out Youth, an LGBTQ youth services agency based in Charlotte. Although he appeared shy with his hands in his jean pockets, he radiated a warm, charismatic energy. I introduced myself to him, and he said I could call him Blake. He cracked a gentle, bright smile when I shook his hand and said how nice it was to meet him.

Blake knew who he was before he had a name for it. “I actually didn’t know I was a female-bodied individual until I was 6,” he told me once on the phone that year. “I always thought I was one of the guys, and one day I was playing outside and I realized I was different.”

TOY’s annual prom allowed him to finally be out as a transgender young man. “It was the first time that anybody had referred to me as my preferred name, my pronouns,” he said. “It was the only place where I felt kind of accepted.”

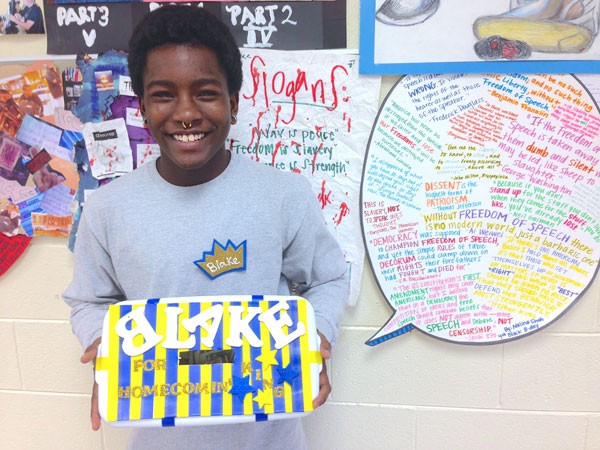

Fast forward to 2014. Blake had turned into a fierce young social activist, joining and often leading young LGBTQ people that were not merely hiding behind Tumblr posts about equality. They were making people take notice in real time. Blake spoke at the Transgender Day of Remembrance. He marched with the Charlotte Activist Collective on Independence Square at Trade and Tryon streets to protest race-based police brutality and led a peaceful die-in at SouthPark Mall. Even being named homecoming king at East Mecklenburg High School was a form of activism. He became the subject of the documentary BrocKINGton, which premiered at the Austin Gay and Lesbian International Film Festival last September.

But there will be no more marches for this beautiful young man. Blake died from suicide at the age of 18 on March 23, TOY confirmed.

I wondered how he felt after the proposed LGBT ordinance, which would have protected transgender people while they used public restrooms in Charlotte, failed to pass on March 2. It wasn’t a bigoted group of people who struck it down — it was one supposedly progressive member of the Charlotte City Council who reneged on one of the six minimum votes needed to pass the ordinance. I wondered how he felt learning some local gay and lesbian people believed an amended version of the ordinance — which gutted public restroom accommodations for transgender people — should have passed to benefit part of the community.

Blake had to fight for LGBTQ equality amid snakes in the grass, those who didn’t believe equality for some is equality and justice for none. Through it all, he remained consistent and true — two traits that will be his legacy.

“Anywhere I go, I introduce myself as Blake,” he told me in 2013. “Even though some people give you crap about it, you can’t say you didn’t try.”