Editor's note: In this series, local author David Aaron Moore answers reader-submitted questions about unusual, noteworthy or historic people, places and things in Charlotte. Submit inquires to davidaaronmoore@gmail.com.

Unlike a lot of Southern cities during the mid-20th century, Charlotte seems to have transitioned relatively peacefully from the Jim Crow era of "separate but equal" to an integrated community - at least according to stories my great aunt told me. Would you say that's an accurate assessment? - Nancy Caldwell, Charlotte

Yes and no. While Charlotte did not explode like Selma or Birmingham, it did experience its share of violence.

Throughout much of its history, Charlotte has been perceived as a non-confrontational kind of city. Cultural and civil changes were slow to arrive because so few people wanted to make the move to push things forward.

In 1957, three years after Brown v. Board of Education, which ruled segregation as unconstitutional, four African-American high school - age students decided to test the ruling.

While America looked on, the teenagers arrived at some of Charlotte's all-white schools as angry crowds gathered to protest. People spat on Dorothy Counts at Harding High School and called Gus Roberts names at Central High. At Alexander Graham Junior High, they shunned Delois Huntley. They did the same to Girvaud Roberts at Piedmont Junior High

Then, in 1960, African-American students from Johnson C. Smith University formed a sit-in at a "whites only" lunch counter at Charlotte's Kress store. Mayor James Smith responded by forming a committee to solve problems brought on by segregation. Soon thereafter, lunch counters were integrated.

By 1965, however, schools in Charlotte remained largely segregated. In January, Darius and Vera Swann decided they wanted their son James to attend school near the family's home. But since the Swanns were black, James was assigned to an all-black school farther away. The NAACP and local attorney Julius Chambers filed legal action against the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education.

Days later, Chambers found himself in a firestorm of controversy.

On January 25, 1965, a dynamite blast destroyed the car that belonged to Chambers. Three men were eventually convicted of the bombing in New Bern; one was identified as the head of the Ku Klux Klan in that area. All were convicted and given suspended sentences. Luckily, Chambers was unhurt, but there was more violence to come.

As the case was argued in court, unknown perpetrators opposed to school integration were plotting to put a stop to Chambers and the NAACP.

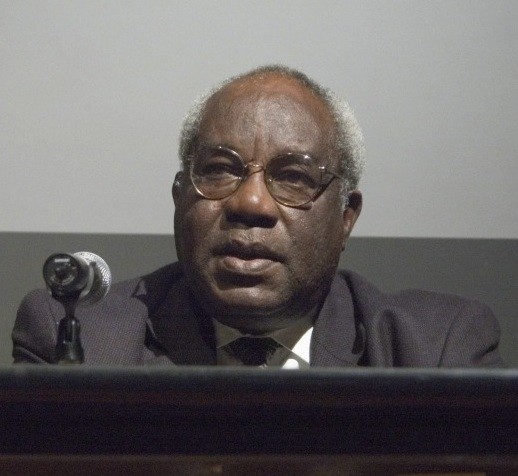

They took aim at four of Charlotte's civil rights leaders: Chambers, state NAACP President Kelly M. Alexander, his brother City Councilman Fred D. Alexander, and Dr. Reginald A. Hawkins.

On the morning of November 23, 1965, between 2:15 and 2:30 a.m., explosions rocked the houses of the four men, all on the west side of town. No one was injured, though flying glass came dangerously close to slashing Hawkins's two children. The most destruction was done to the homes of the Alexander brothers, who were neighbors. Considerable interior and exterior damage was evident. The bombs' impacts were somewhat less extensive at the homes of Chambers and Hawkins, but the mental impact was just as strong.

Police stated that the perpetrators used sticks of dynamite. "It was a well organized group," said police chief John Hord. "I guarantee you it was people who knew what they were doing. Whoever it was, they knew the explosives, they knew the sections and they knew how to get in and get out quickly."

"Anytime four blasts happen like this, it's organized," NAACP leader Kelly Alexander said in the pages of the Charlotte Observer. "I don't know who organized it, but it was an organized force trying to kill us."

Hawkins, whose home was fired upon eleven times the previous August after he testified in a school desegregation case, was confident about who was responsible for the attacks. After the shooting incident, he received a phone call that confirmed the perpetrators. "They called and said it was the Ku Klux Klan. I don't have any doubt it's the same people here," he told the Observer.

The reaction from Charlotteans was a mix of shock, guilt, embarrassment and a desire to reach out and help. Instead of arousing further violence, citizens rallied around the victims.

Community leaders were concerned about how the incident portrayed Charlotte and North Carolina. "We cannot allow anyone to resort to lawlessness and violence - North Carolina's continued progress depends on the maintenance of law and order," said Gov. Dan Moore.

Mayor Stan Brookshire organized a relief fund and raised money to repair the houses. He urged Charlotteans to attend a racial harmony rally the following week. "A large and representative audience will tell the world that Charlotte will not be deterred in its efforts to promote racial harmony and community progress through the fullest possible development of responsible citizenship," he said. A crowd numbering in the thousands showed up for the event.

The fight for desegregation would continue another five years when, in February 1970, federal Judge James McMillan issued a ruling saying that desegregation must begin right away. Within a few weeks, students of all ages were bussed throughout the Charlotte Mecklenburg School system, and black and white children finally had equal access to a public education.

Though some parents complained, school desegregation in Charlotte was finally a reality.

Moore is the author ofCharlotte: Murder, Mystery and Mayhem. His writings have appeared in numerous publications throughout the U.S. and Canada.