Editor's note: In this series, local author David Aaron Moore answers reader-submitted questions about unusual, noteworthy or historic people, places and things in Charlotte. Submit inquires to davidaaronmoore@post.com.

What do you know about Charlotte's Washington Heights neighborhood? I've heard that it was the city's first planned suburban community specifically designed for the African-American community. - Derrick Stafford, Mount Holly

Your information about Washington Heights is correct. In fact, the neighborhood was Charlotte's first and only African-American streetcar suburb.

By the second decade of the 1900s, the Queen City was booming. Nine trolley lines serviced newly created neighborhoods, including Elizabeth, Piedmont Park, Oakhurst, Colonial Heights, Crescent Heights, Club Acres, Wesley Heights, Chatham Estates and Dilworth. More than just an expansion of the city, these new neighborhoods were also meant to assure that neighbors would always be of the "middle-" and "upper-class." House-price minimums were established along with a "race clause," which only allowed Caucasions to own or occupy homes in said neighborhoods. Domestics were, of course, exempt.

Though many, if not most, of the city's African-American residents of the early 20th century were economically oppressed, there was a segment of the population that had obtained middle-income stability and yearned for the same quality of life offered to whites on the east side of town.

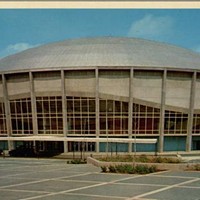

The answer came in the development of a new street-car line and Washington Heights. Northwest of Uptown and across from the old city water works (a classic deco building that was recently refurbished and is once again in use), the Heights was founded in 1913 specifically for middle-income African Americans.

- David Aaron Moore

- The old city water works

Named in honor of revered African-American educator Booker T. Washington, neighborhood streets pay tribute to other black leaders. Davis Avenue was named for Charlotte's pioneer African-American professor George E. Davis; Tate Street, for black Charlotte barber and community leader Thad L. Tate; and Sanders Avenue, named for D.J. Sanders, the first black president of Biddle University, now known as Johnson C. Smith University.

The central street in the neighborhood, Booker Avenue - another homage to Washington - was wider than the rest to make room for a possible expansion of the trolley line.

For middle-income African Americans looking to escape the inner city, the notion of a controlled neighborhood with pricing minimums to ensure like-minded residents was a dream come true. Washington Heights lots ranged from $500 for prime Beatties Ford Road frontage, to $380 in the first block of Sanders Avenue and $300 in the second block of Tate Street. The better-located lots carried a requirement that no house could be constructed for less than $1,000. The minimum price for home construction in the neighborhood was $600. Unlike the blatantly discriminatory white counterparts on the opposite side of town, there were no race restrictions on area residents.

- David Aaron Moore

- Located on Sanders Avenue, this beautiful, old two-story home is a classic example of one of the original constructed for the city's middle-income black residents in Washington Heights.

As of June 1913, 43 lots had been sold. Lot purchases and home construction in the area continued to boom until sometime around 1919, when things slowed because of a nationwide economic depression and a shortage of building materials used instead for the World War I military effort.

An upsurge of commercial growth came by the late '30s and early '40s along Beatties Ford Road. Brick and concrete structures, some two-stories tall, replaced wooden single-story storefronts. Families in Washington Heights could shop at local grocery stores and pharmacies. The community's female population had a number of beauty salons to choose from, while civic leaders took advantage of the nearby fraternal society meeting facilities.

Even though Charlotte discontinued streetcar service in 1938, area businesses are still to be found in abundance where the line once stopped. Clearly one of the most architecturally and historically interesting buildings in Washington Heights is The Excelsior Club, which has been in business since 1946. It is believed to be the one of the longest-operating nightclubs in American history. One of the city's best examples of Art Moderne architecture, it played a key role in the civil rights movement, serving as a gathering place for black political leaders during the '50s and '60s. Over the years it has played host to such legendary musical performers as James Brown, Nat King Cole and The O'Jays. Even in 2013, the legendary Excelsior continues to attract regular crowds Tuesday through Saturday nights.

Although a large portion of the neighborhood was demolished to make way for Brookshire Freeway back in the '70s, what remains of Washington Heights is an important part of the city's history and symbolic of the challenges African Americans struggled against - and, in some ways, overcame - in the 20th century.

- David Aaron Moore

- The Excelsior

Moore is the author of "Charlotte: Murder, Mystery and Mayhem." His writings have appeared in numerous publications throughout the U.S. and Canada.