Jenni Hembree remembers how demanding the guests were when she worked at the Holiday Inn Express in Charlotte, near Independence Boulevard. One required five towels, four pillows and three blankets for every day of the stay. But what Hembree remembers most is her hourly wage of just $10.

In 2009, the 30-year-old started working second shift at the front desk. In her year there, she received two non-negotiable raises at only 25 cents each. By labor standards in North Carolina, where the median wage is $10.05 an hour for a hotel worker per the Bureau of Labor Statistics, it seems Hembree was doing better than her colleagues.

But compared to her counterparts at unionized hotels, Hembree was losing out — and didn't even know by how much. In Washington, D.C., where many of the larger hotels are unionized, hotel workers earn an average of $14.79 an hour, almost $5 more than those in North Carolina. Housekeepers in heavily unionized Las Vegas earn $28,550 a year. Charlotte's earn about $18,780. Hembree says she thought unionization was a stigma in the South, so she did not question how her earnings could increase if she were in one.

"If I were given that option [of a union], I probably would have taken it," she says.

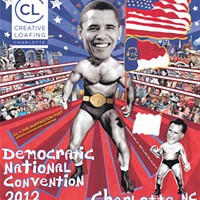

With tens of thousands of visitors expected to pour into Charlotte in early September, a spotlight has been cast on the city's hospitality industry — and, for some Democrats from outside of the state, its lack of unionized hotels. Like plenty of other cities in right-to-work North Carolina, Charlotte doesn't have a single hotel staffed by a unionized workforce.

That fact doesn't sit well with national labor unions, which Democrats heavily rely on not only for campaign contributions but for grassroots, get-out-the-vote operations.

When the DNC Committee announced its potential convention sites two years ago, Unite Here, the largest hotel union in the country, called for Charlotte to be struck from the list. President John Wilhelm argued at the time that union hotels are more likely to have labor practices that align with Democratic Party principles — "good wages, affordable health benefits, stable long-term positions, and respect and a voice on the job," he said.

Melanie Roussell, press secretary for the Democratic National Committee, wouldn't address the city's lack of union hotels or organized labor's disappointment with the Charlotte selection. But she noted that many unions will be in attendance.

"We are pleased with the broad support we have from organized labor to help make this year's convention the most open and accessible convention in history," Roussell said. "The convention in Charlotte will demonstrate what we've been arguing all along — that the president and Democrats are on the side of workers and committed to strengthening the economy from the middle class out."

North Carolina passed right-to-work legislation in 1947, barring contracts that require all workers at unionized companies to pay union dues. North Carolina is now the least-unionized state in the country, with about 3 percent of workers belonging to one, according to the Labor Department. The state also bans collective bargaining for public-sector workers. Feeling snubbed, some unions are skipping the convention in favor of what's been billed as a "shadow convention" for organized labor in Philadelphia.

"This entire saga, from the beginning to today — the site selection, the state selection — the way it's been handled is just nothing more than confirmation to me that the standing of organized labor in the eyes of the Democratic Party is lower than it's ever been in my time," said Chris Townsend, political director of the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America union, who's been in the labor movement for more than three decades.

When it comes to conventions, labor activists take the availability of unionized hotels seriously. They don't like to see so much money pouring into businesses or communities seen as unwelcoming to organized labor. Unions like Unite Here argue that workers like Hembree would be better off if Charlotte's hotel industry had at least some union presence to improve wages and working conditions.

Few hotel workers approached for this story were willing to talk on the record about their working conditions for fear of losing their jobs.

Darren Ash, executive director of Charlotte Family Housing, estimates that about a third of the families seeking help from his homelessness nonprofit are led by parents working in Charlotte's hospitality sector, such as housekeepers.

"These are people who are working, but working at a very low wage," Ash said. "The math doesn't work out for them."

But Alyssa Barkley, the president of the North Carolina Restaurant and Lodging Association, disputes the notion that Charlotte's hotel workers would benefit from unions or that Charlotte's wages are disproportionately lower than elsewhere. North Carolina's right-to-work status has been crucial to the hospitality industry's growth in a "business-friendly climate," she argues.

"Our member hoteliers do not believe that they need a union in order to build a fair, positive and mutually beneficial relationship with their associates," Barkley said in an email. "North Carolina's hotel owners and operators pride themselves on paying a fair wage for a quality workforce. Even entry-level jobs pay well in excess of the minimum wage. Overall, wages and benefits in North Carolina's hotel industry are competitive with that of unionized hotels."

The hubbub over Charlotte's selection as the site of the Democratic convention may say more about organized labor's strained relationship with the South than its strained relationship with the Democratic Party.

Several national hospitality and service-industry unions, when contacted for this story, said they don't have offices or organizers in Charlotte and couldn't speak to the wages or conditions at hotels in town. It's extremely difficult to unionize workers in North Carolina, thanks to its right-to-work status, its public-sector bargaining ban and its long tradition of union-free workplaces. But some Tar Heel labor leaders say that shouldn't deter their Northern colleagues from paying attention to the state.

"I think that ignoring anti-labor states like North Carolina isn't going to help the workers here or change things," said MaryBe McMillan, secretary-treasurer at the North Carolina AFL-CIO. "I wish we did have unionized hotels, and we would if unions would invest in organizing here. To me, the labor movement nationally has ignored the South, to its own peril."

Keith Ludlum said the organized labor community as a whole should have taken the convention as an opportunity to make in-roads in the South.

"This is where we need to be preaching our gospel, where the word is not being heard," said Ludlum, the president of United Food and Commercial Workers Local 1208, in Tar Heel, N.C. "We need to have a wake-up call. [Unions] are on the endangered-species list."

The Southern Workers Assembly is planning to make the most of the DNC. The organization will hold a workers' speak-out on Labor Day, Sept. 3, starting at Wedgewood Baptist Church, which will include information about union contracts. In North Carolina, workers can form a union but cannot legally dictate work hours, wages or employment conditions.

Hembree, who grew up in Texas and moved to Charlotte 11 years ago, never gave unions much thought since they're so taboo south of the Mason-Dixon.

"Part of growing up in the South is you hear about [unions], and the things you do hear are negative," says Hembree, who left the hotel in 2010 after feeling burnt out. She now works as an administrative assistant at a roofing company. "The picture I was given was that they were fighting just to fight about something."

If nothing else, publicity about unions and the convention can introduce the notion of organizing to North Carolina's workers.

"Since I've always worked in North Carolina, and it's always been a right-to-work state, I don't have too much personal experience with [unions]," said one 23-year-old hotel employee, who works in guest services and requested anonymity in order to protect his job. From hearing about the issue of unions and this year's DNC, he "was kind of trying to figure out what it would be like to work in a unionized hotel."

Hembree says that watching her hotel colleagues struggle to make ends meet has opened her up to the idea of organizing, although no union has approached her.

"I feel like you should be compensated for a job," Hembree says, "especially when you're bending over backward to fulfill the needs of someone [else]."