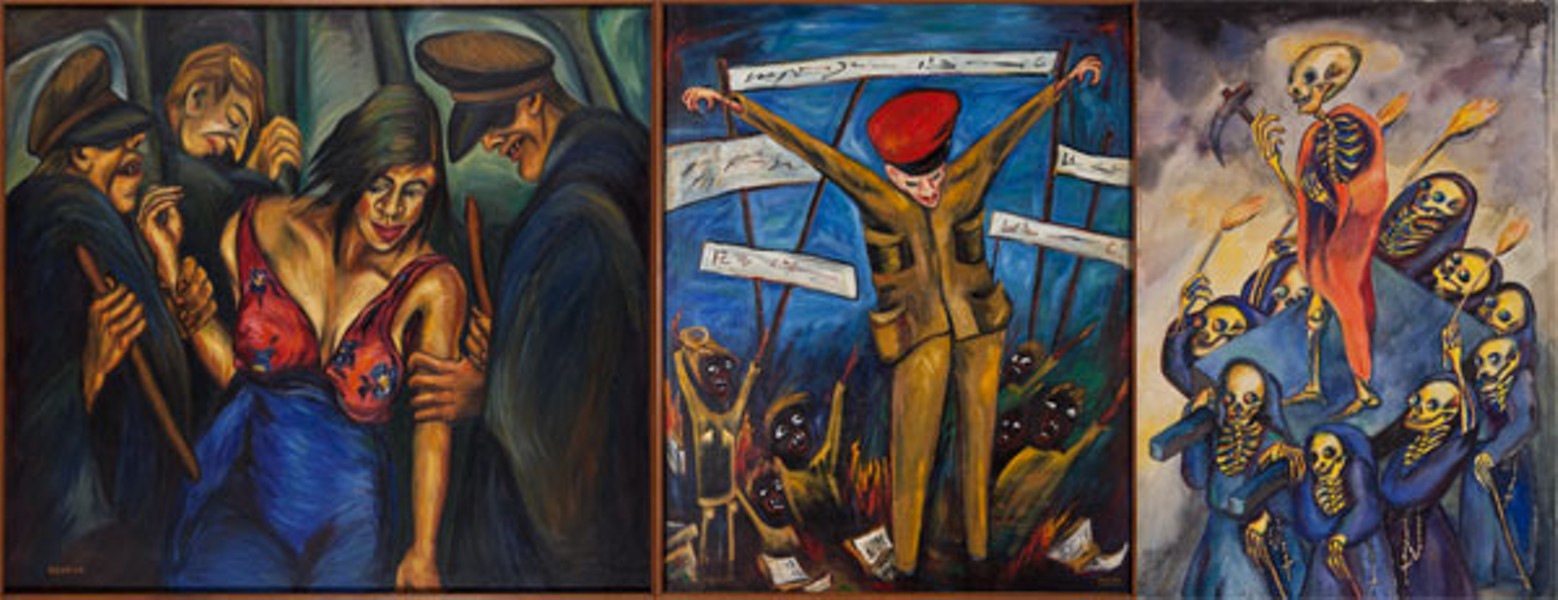

Jarring. Moving. Honest. Blunt. Looking at Colombian artist Débora Arango's best paintings is like listening to Bob Dylan belt out a song decrying the criminal legacy of racism. It ain't pretty, but you're going to stay for the whole song.

The last "best show" at the Mint Museum Uptown, Hard Truths, featured Alabama painter Thornton Dial. His works told the rough story of living black and poor in America's rural South. Sociales: Débora Arango Arrives Today is the title of this new show, but it could easily have been titled Ugly Truths. Her paintings illustrate the seamy and violent side of life in mid-century Colombia, South America — the corrupt, the besieged, the kicked around, and the boots doing the kicking. She did not tread lightly, nor did she speak with a velvet whisper. She was a force to be shunted and silenced, and the powers that be did just that. That's why you've probably never heard of her.

-

PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST AS A YOUNG WOMAN: Débora Arango

Stylistically, Arango is an expressionist painter. Vincent Van Gogh is the spiritual godfather to German Expressionism, and Débora Arango feels like the unclaimed goddaughter to Van Gogh. Arango narrated individual lives of the marginalized horde — prostitutes, women in prison, murdered student protestors, murdered plantation workers and military goons. She also painted women, often naked, who were beautiful and unabashed enough to make nuns run to the sanctuary clutching rosaries while mumbling Hail Mary's.

To my coarse North American eyes, Arango's work is extravagant, cartoonish, unselfconsciously childlike. She paints women like the underground cartoonist R. Crumb would paint women if he could paint. The individuals portrayed here — nuns, sex workers, prisoners, fortune tellers, friends and family — I imagine collectively assembled to form an army of thick, sensuous, strong, independent women. A force deserving recognition and respect, but actually receiving little of either. The men painted here are snarling, leering, ogling, pointy-toothed, unshaven, drunken, slouching, sneering. An expendable bunch of sodden bullies. A force deserving a group spanking.

I spoke with Oscar Roldán-Alzate, chief curator from the Museo de Arte Moderno de Medellín (MAMM) in Colombia. As the curator of this show, he's an animated and enthusiastic advocate for Arango, her legacy and her contribution to the cause of women in Colombia.

"She never considered herself a feminist or a spokesperson for any cause," Roldán-Alzate said. "But today, she is a revered symbol for women throughout Colombia."

Arango did not gild the lily; she gutted it. As a young woman, she looked around the cities of Bogotá and Medellín and saw the foul and the desperate, the cruel and the corrupt, and committed her raw visions to pigment. Her expressions did not endear her to the uber-Catholic, patriarchal, machismo world of 20th-century Colombia. She was embraced by few critics or fellow artists or citizens, and was shunned by many in her years of social commentary, 1938-1960. Her own country warmed to her later, years after the coups, bloodletting and hysteria faded, when clearer eyes could safely revisit, and reassess, the artist's long-stilled voice.

Born in Medellín, Arango grew up the seventh of 12 children in a privileged household. Privilege meant financially comfortable, but for her it meant much more: She was privileged with a liberal and open-minded father. Roldán-Alzate said Arango's father "allowed his daughter to straddle the horse when she rode, not this way" — he illustrated his point by turning his legs side saddle in his chair — "and to drive the family car," unheard of for a woman in 1920s Colombia. He allowed Débora to become Débora; and Débora, unbridled, she became.

She never considered herself a revolutionary, though in her early years she identified with a few, including Mexican muralist José Orozco, a leader in the social realist gang and an advocate for the poor and shunted of Mexico. Arango consorted with all walks of Colombian life — the gentry, the dispossessed, the politically connected, women who spoke when not spoken to and others so radically inclined.

Colombia was in tatters following the fall of the long reign of the conservative elite. Political chaos and civil unrest erupted following the assassination of presidential candidate Jorge Gaitán on April 9, 1948, and ensued until 1958, a period of time known as La Violencia. Arango's workload also erupted. Many writers and artists who witnessed the dissolution would later comment on, and condemn, all that ugly business. She painted what she saw when she saw it. Neither victims nor victimizers within her sphere fared well under her gaze and bristle. No one likes seeing themselves as evil and corrupt and hypocritical and cruel.

"I painted what I watched," Arango once stated. During the years of violence, there was much to see in Colombia. Poverty, hunger, prostitution. Arango chose not to stay within the expected confines of art; she ventured into the streets and into social criticism.

ONE WALL OF the Mint Museum gallery is lined with Arango's portraits from around 1950. Twelve women and one man. Arango once said, "Men never thought much of me, and I never thought much of them." We can see that here. The portraits show a beneficent side of the painter; here, she is the chronicler of the intimate, the agreeable, the lovely. But even here, in both the sympathetic portraits and the nudes, her hand is heavy, forms volumetric, color strident, sometimes clunky. Like Tom Waits singing a lullaby.

- MAMM

-

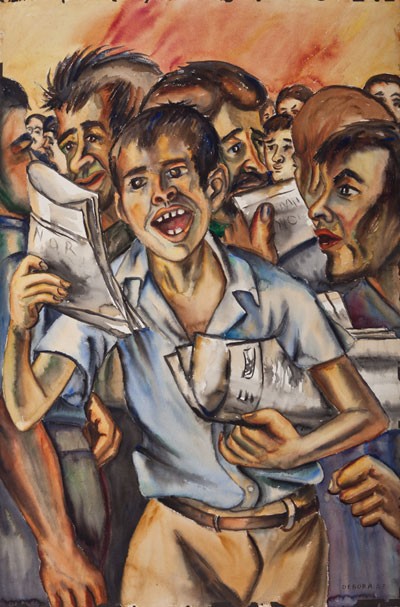

'Voceadores (Town Criers)'

The portraits are not realistic. Arango stays true to form here; she is, after all, expressionistic. The portraits show the inner woman — both the painter and the painted — with only a casual nod to realism. Arango's portraits are less replications of the lines and color and texture of the face, but the lines and color and texture living behind the eyes of the subject. The subject's inner essence, according to Arango. One gets the impression she could not have willed herself to paint any other way.

Arango was marginalized as a woman at home, where women only received the vote in 1954, and only began exercising real political power in the 1980s. She was further marginalized as an artist for being the wrong kind of artist — one who was willing to act as a witness and speak truth to power, instead of painting pretty pictures. She was untethered, undaunted, outspoken and difficult, a problem to those she considered malevolent — tyrants, thugs, deceivers. I asked Roldán-Alzalte, was she not afraid for her life?

"No," he said. "She was not well known, and [her work] was shown little in Colombia until 1970 or so. She worked unseen. Though Débora's brother told her if she kept painting, the whole family would be run out of the country."

Arango was a woman and a painter whose work was considered by many as base, sacrilegious and crudely executed. She was invisible. She plowed forward.

In 1955, Arango was invited by the Institute for Hispanic Culture (for the first and only time) to show her work in Madrid. The show stayed up for a day before closing under orders from the Franco regime. Two years later, she opened her first show at home in Medellín, only to electively pull her own work amid civic and political chaos following the overthrow of Colombian President Gustavo Pinilla — perhaps out of fear of retribution to her or her family. Life was hell in Colombia. She soldiered on.

The public library in Medellín gave Arango her first retrospective in 1977, at the tender age of 69. In 1984, the Museo de Arte Moderno de Medellín honored her with a retrospective showing 205 works spanning 57 years. Things got better for her after that. She received plenty of national and regional recognition — awards, medals and more — until her death, and even beyond. She died, recognized, in 2005. She was 98. She lived in the family house, in Envigado (next to Medellín), for her last 60 years.

What's the take-away with this work, this life? Howard Thurman, spiritual advisor to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., perhaps has the answer:

"Don't ask what the world needs; ask what makes you come alive, and go do it. Because what the world needs is more people who have come alive."

That worked for Débora Arango.