Sydney Jolie Brown extends a little hand to introduce herself even before Renee Brown, her biological mother, does. Kelly Gimlin, Sydney's other mother, stands inside and, with a warm smile, says hello.

On a Sunday night in late April, the family gathers over plates of spaghetti in their kitchen, which overlooks the serene Lake Norman behind their upper-middle-class Cornelius home. Gimlin comments on how good a cook Brown is.

Brown begins dinner by telling Sydney's birth story. "That was a moment of growing up," she says. Gimlin mostly nods and smiles at her partner of more than 15 years. Sydney peppers the story with giggles and asks Brown to define bigger words, like "pragmatic." Brown had old Sydney that her father was an "angel" before the little girl, now 8, was old enough to understand his true role: a sperm donor.

There are other, heavier things that Sydney has heard her moms discuss, more so lately than ever before.

Last year, when Tar Heel legislators decided to put a proposed amendment to the North Carolina Constitution, now known as Amendment One, on the Republican primary ballot, Gimlin and Brown started talking to lawyers. They wanted to make sure legal protections they have for Sydney and their assets remain if it passes on May 8. Amendment One would constitutionalize the definition of marriage as a union between a man and a woman and make that the only domestic legal union recognizable by the state. What frustrates Brown and Gimlin is the uncertainty.

If Amendment One passes (and polls are showing that's likely) and Brown were to die, the state could take everything, including Sydney, away from Gimlin. It would be one of the most stringent laws to address domestic partners — some 228,000 in North Carolina, according to the census — on the books in all but three states, and would have severe consequences for couples like Brown and Gimlin, who brought Sydney home from the hospital together.

At this point in the conversation, Gimlin turns to Sydney, who's almost finished with dinner, whispers something in her ear and kisses her cheek. Sydney gets up from the table and walks to her room.

A slew of the largest medical and psychiatric organizations in the country, including the American Medical Association, the American Psychological Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics, have passed resolutions supporting "full, legal marriage equality," most on the heels of North Carolina legislators affirming the amendment in September. On April 5, the North Carolina Pediatric Society, Psychiatric Association, Psychological Association and the North Carolina branch of the National Association of Social Workers gathered in Raleigh to voice their opposition to the amendment, citing its "potential for producing a devastating effect on the health of North Carolina families." Two days later, the state superintendent came out against the referendum saying it was "not in the best interest of our children or our state for the amendment to pass."

"This amendment has the potential to negatively affect the physical and mental health of approximately 900,000-plus North Carolina children who will at some point live in a cohabiting household," wrote Jean Aycock, a Raleigh-based psychiatrist. "It appears that Amendment One is as much anti-child as it is anti-gay, and anti-public health in all regards."

Since the Defense of Marriage Act was passed in 1996, 30 states have enacted constitutional amendments banning same-sex marriage. Additional states have instituted laws restricting marriage to heterosexual couples and limited the rights of gay couples and individuals. Researchers have worked since to understand the psychological effects of such legislation on the gay community.

A nationwide study of U.S. adults found that lesbians, gays and bisexuals living in states with constitutional amendments banning same-sex marriage during the 2004 elections had significant increases in mood, anxiety and substance-abuse disorders, according to a report by Yale University's Mark L. Hatzenbuehler. Conversely, in Arizona, the only state to not pass its anti-gay marriage amendment on the ballot in 2006, similar respondents experienced fewer depressive symptoms than those living in states that passed their amendments, according to researchers at the University of Kansas.

With a 157-0 vote to support marriage equality, the American Psychological Association concluded that the emerging research shows such laws have negative effects on the psychological well-being of gays, lesbians and bisexuals. The medical association determined the harm of such legislation would affect not only lesbian and gay individuals and couples, but their families as well. There are an estimated 27,250 same-sex couples in North Carolina, 23 percent of which are raising children, according to a UCLA study based on 2010 Census numbers.

Brown has the kind of confidence executives exercise in a board room. She looks at you in the eyes when she talks because she knows that's an effective way of making a point. As the director of marketing for the wealth, brokerage and retirement branch of San Francisco-based Wells Fargo & Co. she knows how to choose her words carefully. As her lake-front home shows, she's had a successful career, one that maybe wouldn't be so fruitful had she not grown up in a conservative household where she became an overachiever to compensate, she says, for being different. Even though her sister, her only other sibling, is lesbian as well, her parents still weren't accepting. For Brown and many others, the fight for acceptance started long before Amendment One.

"I have to come out every day," the 41-year-old says.

Gimlin was also raised in a conservative household but is the only gay among five siblings. Since Amendment One was announced, the stay-at-home mom has become a grassroots organizer, dispensing anti-amendment signs to her neighbors or "to anyone who lives in a high-traffic area," she says. Gimlin opposes Amendment One to friends and even strangers but decided early on she wouldn't try to convince her biggest challenge: her mother.

"I'd rather change everyone else's mind, not hers," Gimlin says. "It's like talking to a brick wall."

Her mother accepts Gimlin, Brown and Sydney, but not the "others."

"It's kind of like she's saying she doesn't love me." Gimlin hesitates to discuss their relationship and sounds defeated when she does, as if she's debated about it for years in her head and, for years, has lost.

One hundred and forty miles away in Chapel Hill — which seems, to some, like a million miles from Cornelius — Terri Phoenix sits at her desk on UNC's campus. The director of the LGBTQ Center is skeptical of the Triangle city's progressive reputation. When the group posts signs around town for the center's events, half are usually torn down.

Phoenix has short hair and prefers suits and ties to dresses and heels. Though she's been out as a lesbian for a long time, she says she'll be apprehensive to travel to more rural parts of the state, giving lectures as she normally does, dressed the way she normally does, if Amendment One passes. Or even if it fails.

"Even when a significant victory [for the LGBT community] occurs, you see an increase in hate crimes immediately after," she says, noting the spike in hate crimes that followed the passage of the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act in 2009.

Just the debate surrounding policies like Amendment One is enough to exacerbate the negative climate outside and within the gay community, according to Hatzenbuehler's research, published in the

American Journal of Public Health. Lesbians, gays and bisexuals living in states that argue such policies report an increase in negative stereotypes in the media, hostile interactions with neighbors, colleagues and family members. The research shows exposure to such attitudes can lead to greater shame within the community.

Lesbians, gays and bisexuals polled in Colorado after it passed Amendment Two, which would have denied them certain legal protections had it not been overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court, noticed an increase in negative media portrayals, anti-gay graffiti, comments and jokes, and reported a lost sense of safety, according to a 2003 study by the Institute for Gay and Lesbian Strategic Studies in Amherst, Mass.

"It's a pretty horrible feeling when I read the most recent policy poll that said how many people were going to vote in favor of Amendment One. Rights of the minority put up to vote of the majority," Phoenix says.

Though polls have reported slightly more optimistic results leading up to May, Amendment One still confuses voters. The most recent Public Policy Poll shows 40 percent of North Carolina voters oppose Amendment One and 54 percent support it — the lowest level of support it's found in monthly polling since October. Twenty-six percent of voters think Amendment One bans only gay marriage, 10 percent think it legalizes gay marriage and 27 percent admit they don't know what it does.

"If this thing passes, I'll feel rage, disappointment, just crushing sadness, and confusion," Phoenix says. "Either way, on May 9, North Carolina is going to look different."

Amendment One is stricter than laws in all but three states — Idaho, South Carolina and Michigan — because it says that marriage between one man and one woman is the only domestic legal union North Carolina can recognize. Because the phrase "domestic legal union" isn't defined in the amendment and has never been used in North Carolina laws or defined by North Carolina courts, it is unclear how judges would interpret it, according to a report from instructors at the UNC Chapel Hill School of Law.

What is clear, the lawyers say, is that the amendment could bar the state from giving unmarried couples of any sexual orientation the right to determine how to dispose of their partner's remains and how to handle medical emergencies or financial decisions. It could invalidate trusts, wills and domestic-violence and child-custody laws. It would make it that much harder for Gimlin to adopt Sydney, which Brown says they've already decided against because of the legal process it would require. (As the law stands, Gimlin has to sue Brown to qualify for second-parent adoption.)

"Our straight counterparts don't have to do this," Brown says. "This is a civil-rights battle."

Brown, who regularly travels for work, was on a flight leaving Philadelphia early in the morning on Sept. 11, 2001, when, right before take-off, a flight attendant announced that the U.S. had been attacked. She said that the plane — and all others across the country — was not taking off. Deplaning passengers were met with a flood of uniformed National Guardsmen. Between chaos and confusion, Brown and someone she met on the plane agreed to rent a car that would take them to their respective homes. Gimlin was glued to the phone in North Carolina, but faulty reception left her in the dark for hours. In the mean time, Brown had stopped at a Walmart just outside Philadelphia when a low-flying plane cast a shadow on the parking lot.

"All planes were grounded at that time," she says. "It had to be that plane."

The experience left a profound impact on Brown and Gimlin. It made them want to put something positive back in the world, Gimlin says. Two years later, Brown got pregnant.

-

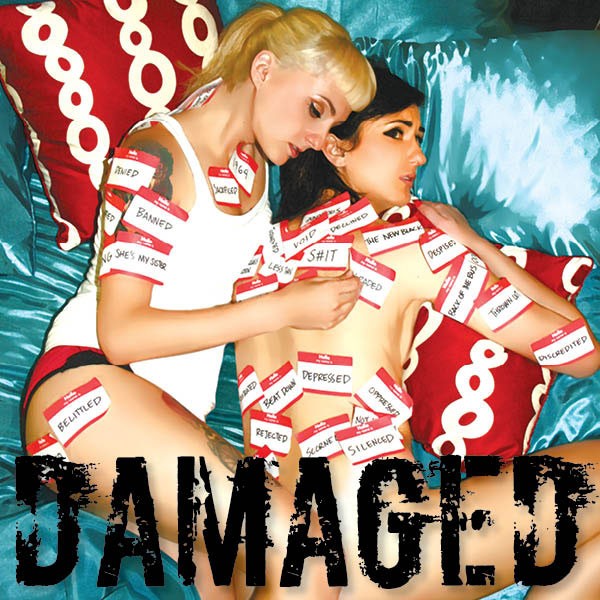

Classic family photo (Graham Morrison)

Sydney's home life is different from other children's. She hears her parents talk about what will happen if one dies. She hears them joke about how the state essentially sees them as roommates. Though they take her to a supportive church and surround her with supportive people, they know that they can't control what's beyond their inner circle. She's in private school, and Gimlin and Brown are uneasy about sending her to public school, especially as she approaches the cruel world of junior high.

Her peers are already questioning her moms. When they ask, Sydney just says she has two. When they ask why, she says she doesn't know. The children always walk away satisfied with the answer, Gimlin says.

"They don't think it's a big deal until they're told it's a big deal."